(first posted 11/24/2012) Every silver lining has a cloud, and the Corvair’s is a deadly thunderhead. We’ve reveled in our love for the Corvair on these pages repeatedly, (here, here, and here), and shown how the 1960 Corvair sparked a global design revolution. But for all of our silver-tongued love sonnets for the most unique and refreshing car to escape Fortress Detroit in decades, we’ve so far avoided its very controversial shadow side. No longer; get out your umbrellas, for a hard rain’s gonna’ fall.

The most fundamental question has to do with the decision to make the Corvair a rear-engined car, as all of its issues ultimately stem from that. According to the oft-repeated story, in 1955 Chevrolet Chief Engineer Ed Cole asked Maurice Olley, the division’s Director of Research, to analyze the various engine-drive train variations for a small car, including conventional front engine-rear wheel drive, FWD, and rear engine variations. A number of small European cars were tested and examined, and the rear-engine configuration as used by VW and the smallest Renaults and Fiats was determined to be the most advantageous for a number of reasons.

Those were its light steering (power assist not necessary), a flat floor, a relatively quiet and comfortable ride, and excellent traction. It’s important to keep in mind that at this stage, the Corvair was envisioned as a more compact and cheaper alternative to the full-sized Chevrolet, not the sporty car that it eventually evolved to be.

Specifically, the Corvair project was to take up where the 1947 Chevrolet Cadet had failed: to be a profitable compact car. And the way that “compact” was defined then was for the car to be shorter and lighter, but still be able to accommodate six. That presented inherent challenges in packaging the drive train.

The solution then was Cadet Engineer Earle MacPherson’s use of his eponymous struts at both front and rear, combined with an independent rear suspension and the transmission under the front seat. A rather brilliant solution from a brilliant engineer, but this was not France or Germany where such an advanced car could be priced accordingly. The Cadet suffered from a recurring GM malady: technical overkill, given the cost structure of the US market. Wouldn’t a more conventional car seating perhaps merely five have been adequate?

The also-brilliant Ed Cole fell for similar trap, although in terms of construction costs, the Corvair probably was presumably profitable to build, despite the huge investment in unique facilities to build its engine. By trap, I mean the hubris of being convinced that he could find a low-cost solution to the problems that had long stood in the way of building a six-passenger rear-engine car.

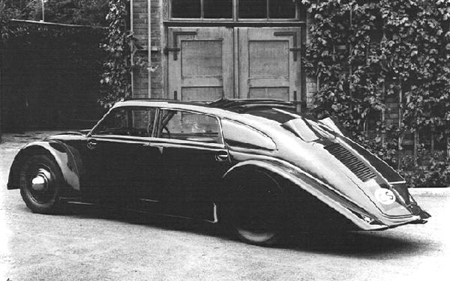

The rear engine was the hot new thing in the early thirties, along with aerodynamics. Tatra epitomized and popularized both of those, and others quickly took them up too, at their peril. The first large V8 Tatra streamliner, the 77 (above) suffered from very severe handling problems, and was built in only limited numbers.

Its successor, the 87 (above) was shorter and lighter and had a smaller 3.0 L air cooled V8 in its tail, but its snap oversteer at the limit–thanks to its rear-weight bias and swing axles–was still deadly. So much so, that Hitler banned his top officers from driving it, after a number were killed in high speed accidents. It was dubbed “The Czech Secret Weapon”.

Mercedes, that paragon of engineering prowess, also took up the rear engine, but more cautiously. Its 130H, 150H and 170H (above) were built alongside conventional models. They sold poorly, in part due to a smaller luggage area, noisy engine, and bad handling vices. The positive rear camber clearly visible in this picture is a tip-off to that.

Mercedes dropped the rear engine, but did adopt swing axles, and eventually made them work quite successfully thanks to the better weight distribution of front engines and constant improvements in their geometry. By the late fifties, Mercedes had tamed it almost completely, with its exclusive “low-pivot” variation, but that was not suitable for a rear-engine car.

Of course it was the Volkswagen that popularized the rear engine, and the even-smaller Renault 4CV and Fiat 600 followed in its swing-axle tracks. But these were all small cars, with low power outputs. Even then, they were still susceptible to the dreaded effects of snap-oversteer and rear-wheel jacking. Needless to say, the early Porsche 356s were famous for their oversteer, but that was tamed to various degrees by initial negative camber, and in 1959, a revised rear end with softer torsion bars and a camber compensating spring.

When the rear end of a swing-axle car approaches or exceeds its limits, the centrifugal forces acting on the rear of the car causes the outside wheel to tuck under the body, which results in the rear rising and drastically exacerbating the intrinsic oversteer of a rear-engined car. This picture shows a front-engined Triumph Spitfire; rear engined cars can respond even more violently because of the high percentage of weight in the back. It’s very easy to lose control, unless one can anticipate the event, or forestall it with deft counter-steering. But that isn’t always possible, even in the hands of experienced drivers.

Maurice Olley, who was charged by Ed Cole to evaluate the various configurations, had written about the intrinsic limitations of the rear-engine format. From Ralph Nader’s “Unsafe At Any Speed”:

(Olley’s) field of specialization was automobile handling behavior. In 1953 Olley delivered a technical paper, “European Postwar Cars,” containing a sharp critique of rear-engined automobiles with swing-axle suspension systems. He called such vehicles “a poor bargain, at least in the form in which they are at present built,” adding that they could not handle safely in a wind even at moderate speeds, despite tire pressure differential between front and rear. Olley went further, depicting the forward fuel tank as “a collision risk, as is the mass of the engine in the rear.” Unmistakably, he had notified colleagues of the hurdles which had to be overcome.

So why did Cole go for the rear engine anyway? Despite the rep engineers have for being objective, it seems quite likely he wasn’t in this particular case. Cole had been intrigued with both rear-engines and air-cooled ones for some time, having been involved with an experimental rear engined Cadillac that had dual rear wheels to help deal with its severe intrinsic challenges. He also was involved with the M41 Light Tank that used an air-cooled flat six. Undoubtedly, he was prejudiced to some degree, and convinced himself of the rear-engine’s assets.

Seeing that this was the mid-late fifties–and GM–there was another important factor: trendy good looks. Which meant a very low car, among other things.

In January 1960, (Corvair project head) Kai Hansen told a meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers: “Our first objective, once the decision was made to design a smaller, lighter ear, was to attain good styling proportions. Merely shortening the wheel base and front and rear overhang was not acceptable. To permit lower overall height and to accommodate six adult passengers, the floor hump for the drive shaft had to go. Eliminating the conventional drive shaft made it essential then that the car have either rear-engine, rear-drive or front-engine, front-drive. Before making a decision, all types of European cars were studied, including front-engine, front-drive designs. None measured up to our standards of road performance.”

The result was a total height of 51.3 inches–extremely low for a six-passenger sedan–and lower than a current Porsche 911 Carrera. It’s quite clear that the rear engine configuration ultimately was selected for the sake of stylistic vanity, or in their words “the most aesthetically pleasant” way to achieve the desired space. The Corvair looked like a scaled-down full-size car, and that could only be achieved by making it lower. Which in turn demanded a rear engine. And once that ill-advised decision was made, GM was not prepared to spend the money to make it work properly.

One only has to look at Chevrolet’s own boxy front-engine rear-drive compact, the 1962 Chevy II, to see how tall it needed to be in order to have roughly the same interior space. This is exactly what the GM stylists were hoping to avoid with the Corvair.

All of the European rear-engined sedans GM had evaluated were much smaller four-passenger cars, with very small and light four-cylinder engines. A four-cylinder engine was originally considered for the Corvair, but abandoned for a six because of its greater smoothness. A boxer four is intrinsically a balanced design, but is prone to some exhaust growl due to its firing order. But that can be mitigated by exhaust system tuning.

Ed Cole’s initial plans and calculations were for the Corvair to use aluminum cylinders with a high-silicon alloy, similar to that later used in the Vega. Perhaps from a durability point of view, it was for the best that it was not feasible then, and individual finned cast iron cylinders were ultimately used. This contributed to the production Corvair engine weighing 332 lbs, 78 lbs more than initial projections.

That’s a full 50% more than the VW’s engine, which weighed 220 lbs. And being a four cylinder, the short VE engine didn’t stick out as far in the back as did the Corvair’s, which further affected weight balance negatively. And to make things worse, starting in 1961 Chevrolet moved the spare tire from the front trunk to the engine compartment, increasing rear weight bias further.

Needless to say, in a rear engine car the greater the weight in the back, the greater the challenges and risks, due to the intrinsic influence of centrifugal force in a curve. Production Corvairs had up to 64% of their weight on the rear wheels, a problem further exacerbated when the spare was moved from the front trunk to the engine compartment in 1961 due to complaints about trunk space. The VW carried 57% of its weight over the rear wheels. In a rear engine car, every percentage point of additional weight becomes disproportionately problematic in terms of stability, given the crude swing axle suspensions then in use.

Without going into all the technicalities of the specific choices made by the Chevrolet engineers, it is apparent that one over-riding criterion was predominant: cost control. Charles Rubly, a Corvair engineer, made the following comment at an SAE meeting in April 1960:

Another question that no doubt can be asked is why did we choose an independent rear suspension of this particular type? There are other swing-axle rear suspensions, of course, that permit transferring more of the roll couple to the front end. Our selection of this particular type of a swing-axle rear suspension is based on: (1) lower cost, (2) ease of assembly, (3) ease of service, and (4) simplicity of design. We also wished to take advantage of coil springs … in order to obtain a more pleasing ride …”

Having made their decision on the basic configuration, there were several ways available to mitigate the intrinsic tendencies of the Corvair’s suspension design. A front roll bar (estimated to cost $4) was originally intended to be used, for its (debatable) effect in compensating oversteer to some degree.

More critically, a rear camber-compensating spring was not used, despite the adoption of one by Porsche, and a large aftermarket for that developed for VWs, Renaults and older Porsches. This device had come to be seen as the most critical element in taming the vices of rear-engined swing-axle suspensions.

Given the $19.95 retail price of the EMPI Camber Compensator, it probably would have cost Chevrolet some $15 or less in mass volumes to buy and install. A whole industry grew around Corvair chassis improvements, as serious Corvair drivers were all-too aware of its limitations:

By 1963, sports car racer and writer Denise McCluggage could begin an article on Corvair handling idiosyncrasies with words that assumed a knowing familiarity by her auto buff readers: “Seen any Corvairs lately with the back end smashed in? Chances are they weren’t run into, but rather ran into something while going backwards. And not in reverse gear, either.”

Then Miss McCluggage went on to describe a phenomenon she termed a “sashay through the boonies, back-end first.” “The classic Corvair accident is a quick spin in a turn and swoosh! — off the road backwards. Or, perhaps, if half- corrective measures are applied, the backward motion is arrested, the tires claw at the pavement and the car is sent darting across the road to the other side. In this case there might be some front end damage instead.”

And noted race driver and Corvair-tuner John Fitch had this to say: “I didn’t want a race car,” he said, “if I did, I’d buy something for that purpose. But I did want to feel more confident when behind the wheel that the car would go where I pointed it.”

Instead, Chevrolet jiggered with the tire pressure differential, arriving at a somewhat ludicrous 15 lbs front, 26 lbs rear recommendation. The benefits of the differential were known, as the lower front pressure increased understeer to counteract the oversteer. But there were several fatal flaws in these numbers, which were obviously arrived at in a desperate attempt to maintain the vaunted GM soft ride.

To start with, 15 lbs in the small 6.50 x 13″ front tires reduced their load capacity precariously low, again considering the six-passenger seating and luggage capacity. But the more critical issue was the rears, as they were also technically overloaded with just two passengers at 24 lbs. And 26lbs was not enough to ensure that the tubeless tires would resist deflection to the point of popping off the rims under the extreme pressures in a critical handling situation; specifically an oversteer/jacking up incident.

Shortly after the 1960 Corvair was released, a number of tragic accidents occurred, and it was noted that the pavement often showed severe gouging. This was the result of the rear tire popping off the rim, which then contacted the pavement and had the effect of drastically escalating the incident into a severe or deadly accident.

Popular entertainer Ernie Kovacs was killed in his 1961 Corvair Lakewood wagon (which had an even more exaggerated rear-weight bias) when he lost control on a rainy evening in Los Angeles (picture at top of article). Note the right rear tire that is off the rim; it’s possible that happened from the curb, but it is typical of numerous similar incidents where the rear tire rolled off the rim during an emergency maneuver and caused the Corvair to be essentially uncontrollable.

Corvair engineers knew about this problem and considered raising the recommended rear tire pressures. Once again, however, they succumbed to the great imperative-a soft ride. Rubly recounts it plainly enough: “The twenty-eight psi would reduce the rear-tire deflection enough but we did not feel that we should compromise ride and add harshness because under hot conditions tire pressures will increase three to four psi.”

Even if the recommended inflation numbers had been increased with a similar differential, say 19/28, there was still another huge obstacle: essentially no one in America was used to the concept of a differential tire pressure. When I was a gasoline station attendant in 1968-1970, we inflated all car tires to 24-26 lbs, unless told otherwise. Which we never were, except the occasional sports car fanatic who knew and cared about such things.

Chevrolet made no effort to educate its dealers and the public on the importance of these differential tire inflation recommendations. As well, there was no reference to “oversteer” and how to identify it and compensate for it by counter-steering in the Corvair Owner’s Manual or elsewhere. This was an innately counter-intuitive thing to do for Americans that had grown up with understeering cars, and were repeatedly told in Driver’s Ed to “steer into the skid”, not against it.

The issue GM and other American makers using cheaper undersized tires has been a recurring one (and one we’ve covered here). VW, Porsche and Renault used 15″ tires on their rear-engine cars. And interestingly enough, the 1961-1963 Pontiac Tempest, which used a modified version of the Corvair’s swing axle rear suspension (but with a front engine), bucked the trend and was the only GM car during that whole era to use 15″ tires exclusively. That looked rather odd at the time, but undoubtedly was a conscious decision at Pontiac based on the belief that larger diameter tires would mitigate the swing axle’s tendencies.

Pontiac had been on track to have its own version of the Corvair for 1961, dubbed Polaris (above, and which also looks to have substantially larger tires that the Corvair). The division had already spent some $1.3 million in adapting the Corvair, before John DeLorean pulled the plug. He was convinced by his top engineers, including Advanced Engineering Chief Albert Roller, who had come from Mercedes-Benz: “(he) tested the car (Corvair) and pleaded with me not to use it at Pontiac…he said that Mercedes had tested similarly-designed rear-engine swing-axle cars and had found them too unsafe to build”.

DeLorean got approval to dump the Polaris project, and instead adapted the front engine Buick-Olds compact, but not without some creative engineering, including the swing axle rear suspension. And as it turned out, even the Tempest came in for criticism due to its turning nasty in extreme situations. It was a short-lived experiment.

DeLorean also alleges in his book “On A Clear Day You Can See GM” that the problems with the Corvair’s handling were all-too well known inside GM. He says that Frank Winchell, then a Chevy engineer, flipped one of the first prototypes, and others followed. A huge internal fight ensued, with Ed Cole and his camp on one side, and a number of top engineers on the other, including Charles Chayne, VP of Engineering, and Von D. Polhemus, GM Chassis Development head. Their efforts to keep the Corvair from production, or change its suspension was a lost cause, as “Cole’s mind was made up”.

A number of GM executives were directly affected by the Corvair, including the death of the son of Cadillac General Manager Cal Werner, and the critically-injured son of Exec. VP Cy Osborn. Of course these represent just a small sampling of the accidents that the public was experiencing, and which soon led to a spate of lawsuits against GM, most of which were quickly settled.

Undoubtedly, driver negligence was involved in some of these cases, but there’s also no doubt that the Corvair’s unique response to sudden steering, brakes or other inputs created a situation the general public was unfamiliar with. And one that could be exacerbated by incorrect tire pressure.

In a partial response, for 1961 Chevrolet made available an optional RPO 696 sports suspension, which included stiffer springs and shocks, the previously-missing front anti-roll bar, a negative initial camber setting for the rear wheels, and rear-axle rebound straps to reduce tuck under, all for some $10 or so. My 1962 Monza four-speed had it, and it performed admirably enough under lots of spirited cornering. But then I also knew of the ultimate danger and respected the Corvair’s limits, except on certain snowy parking lots or frozen lakes. Nevertheless, the camber-compensating spring was still not installed or available.

And the sports suspension had its limitations too, reducing rear wheel travel due to the negative camber and stiffer springs. This made it less than ideal for the kind of use a family sedan might typically get, with heavy loading and such. Chevrolet had put themselves between a rock and a hard place with the Corvair’s suspension design.

DeLorean says that after Bunkie Knudsen took over at Chevrolet in 1961, he was so concerned about the Corvair’s handling issues that he demanded that the camber-compenstor be made standard. The roughly $15 cost to make and install it was deemed too expensive by the “Fourteenth Floor”, and he was turned down. Eventually he gave the top brass an ultimatum: either he would be allowed to improve the Corvair’s suspension, or he would very publicly resign from GM over it. They relented, and that led to the camber compensating spring in 1964, and the complete redesign of the rear suspension for 1965, which essentially eliminated the issues altogether.

Ralph Nader’s “Unsafe At Any Speed” is commonly blamed for the Corvair’s demise, but that already happened years before its publication in 1965. By that time, the Corvair was already on artificial life support. Within two months of its introduction in the fall of 1959, Ed Cole realized that the Corvair was not really the right formula for what America was looking for in a compact sedan. The Falcon instantly outsold it two-to-one, and Cole ordered a crash program to develop the very pragmatic Chevy II.

From that point forward, the Corvair’s future, to the extent it had any, was in its new role as a sporty coupe, and the bucket-seat Monza immediately became the best selling version after it was introduced in the spring of 1960. The Monza pioneered a whole new market segment that would be taken over by the Mustang in 1964.

Given how obvious that was by mid-1960 makes it even odder that GM resisted the efforts to adopt wholesale the suspension improvements readily available. One thing is clear: Ed Cole did not set out to design a sporty car. The up-scale Monza coupe was shown as a show-car concept in January of 1960 to generate some interest in the coupe version due shortly (in 500 and 700 trim levels), but the public response to the Monza was so favorable, it was rushed into production.

The Monza inadvertently created and opened a huge market segment (we covered that here) which led to bucket seat versions of its competitors, as well as the Mustang. But a flat floor and seating for six was certainly not in the brief for a sporty coupe or convertible, as the Mustang proved convincingly. Unless you like your passenger to squeeze left.

The Monza may have pulled some of the Corvair’s fat out of the fire, but that doesn’t negate the fact that Ed Cole’s Corvair was a fatally flawed design for its original intended role. In fact it’s tempting (and fairly easy) to speculate that if Chevy’s 1960 compact had arrived in more conventional front-engine form, like the related B-O-P 1961 compacts, that it would have just as readily (and likely) spawned a sporty coupe variant with V8 power, one that would have largely usurped or dampened the Mustang’s huge success.

The Corvair was the product of GM’s repeated tendencies to go off in directions that were an engineer’s dream, but were either flawed from the initial concept, or diminished by the bean counters. In the case of the Corvair, it was both. But for us lovers of the Corvair, like the lovers of the 1966 Toronado, the Vega, and other GM Deadly Sins, it was a huge boon. Suspension mods are easy to effect, and Corvairs are now safely in the hands of those that understand and respect its limitations (and tire pressures). But that was not the case in 1960 or so, and probably more than needed to paid the price.

Related reading at CC:

“Unsafe At Any Speed” Turns 50: The Most Influential Book Ever On The American Automobile Industry

How The 1960 Corvair Started a Global design Revolution

1960½ Corvair Monza Coupe: The Most Influential Car of the Sixties

What If? 1961-1964 Corvair Monza Hardtop Coupe

1961 Corvair Rampside: It Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time

1962 Corvair Lakewood Station Wagon: Why Did We Go Ahead And Build This?

1963 Corvair Monza Spyder Convertible: The Turbo Revolution Started Here

1963 Corvair Greenbrier: We Don’t Want A Better VW Bus

Auto-Biography: 1963 Corvair Monza (My First Car): The Tilt-A-Vair

1964 Corvair Monza Spyder: Activate The Turbo Scat

1965 Corvair 500: Double Or Nothing!

1966 Corvair Monza Coupe: The Best European Car Ever Made In America

I know this is really about the Corvair, but also Nader. I remember reading his book in the mid/late 70s and thinking, this guy doesn’t know anything about cars. Not that Corvairs were perfect, but Ralph was a lawyer, not an engineer. I think his heart was in the right place, but he just didn’t know what he was talking about.

i have not had the time to actually read the full story. I glanced through and perused. What I have noticed is that the majority of the “design flaw” talk is about the handling of the car. I have seen very little written regarding the most deadly design flaw of this car. That being the gas tank in front and its explosive effects. Growing up fatherless due to this explosive effect, Ii wonder why this topic is not discussed as the major design flaw. Anyone care to comment.

Two reasons come to mind: the booby-trap handling was probably a much more frequent cause of Corvair crashes (…injuries, deaths…) than the gas tank, and fuel systems on all American-market cars were uncrashworthy (fire-prone) prior to the 1977 advent of Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 301.

One of Ford’s LP-record-plus-filmstrip creations for its salesmen here pointing up Falcon advantages vs Corvair: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ShBoZt71pbs

And then there’s Chevy’s presentation taking the opposite side: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j3UE5UOjpXA

Ford even brings up the unusual tire pressure thing (image below):

If anyone wants to actually read the NHTSA report, it’s publicly available (it’s a work of the federal government) and can be downloaded in PDF format from the National Technical Reports Library:

https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/dashboard/searchResults.xhtml?searchQuery=corvair

The report is entitled “Evaluation of the 1960–1963 Corvair Handling and Stability” and is listed under accession number PB211015. It’s 140 pages.