The 1961 Continental may have been a classic design, but by 1969, it was getting both old and jowly. For 1970, the Continental received its first full redesign in a decade. Let’s take a look at what changed and why, including an article from the August 1969 Motor Trend presenting the highlights of the all-new 1970 Lincoln Continental.

New Continentals for Old

At some point, every automotive design, no matter how brilliant, goes from fresh to familiar to just old. From there, it might eventually graduate to classic, or at least fashionably retro, but automakers are far more concerned with sales volume, market share, and return on investment, whatever posterity might say.

The 1961 Continental had been conceived as a two-door Thunderbird proposal, but became a four-door sedan (and four-door convertible) in a last-ditch attempt to revive Lincoln, whose poor late ’50s sales had brought it close to the chopping block. Though never a big seller, the critically acclaimed design, a pared-down lineup, and Ford’s need to fully utilize the Wixom assembly plant the Continental shared with the Thunderbird managed to keep Lincoln viable through the early ’60s.

1961 Lincoln Continental sedan / Ford Motor Company

Over the next nines years, there were nips, tucks, minor facelifts, and an endless assortment of new grilles. The Continental lost its curved side glass for 1964, only to regain it a few years later. A two-door hardtop returned to the line, and the slow-selling convertible vanished. A bigger 462 cu. in. (7,550 cc) V-8 replaced the original 430 cu. in. (7,050 cc) MEL engine, the modern C6 automatic replaced the older Turbo Drive, and front disc brakes were added for 1965.

1969 Lincoln Continental Coupé / Ford Motor Company

Despite all this shuffling, the 1968–1969 Continental was still more or less the same car it had been in 1961. It looked bulkier, though, and was — it had gained about a foot in overall length and around 150 lb, partly offset by the introduction of the new 460 cu. in. (7,536 cc) 385-series V-8, which was about 59 lb lighter than the 462.

The Continental had never been a lightweight, and its unitized construction hadn’t helped. Unlike the original Falcon program, where weight reduction was such a priority that engineers had to sign written weight commitments, the structural design philosophy for the big Lincolns and 1958–1966 Thunderbird had been “add more metal until it stops breaking.” The ’61 Continental had been lighter than its gargantuan predecessors thanks to its smaller exterior dimensions, but a fully equipped sedan still tipped the scales at a hefty 5,268 lb. A loaded ’69 Continental hardtop coupe was 5,362 lb, and the ’69 sedan added 95 lb on top of that — heavier than most contemporary body-on-frame cars the same size.

Ford had already switched the Thunderbird to a perimeter frame for 1967, and the new Continental Mark III — which was basically a long-wheelbase Thunderbird with neo-classical styling — shared its perimeter frame with the four-door T-Bird. Now, it was time for the aging Continental to go the same way. Here’s how Motor Trend editor Bill Sanders explained the changes in August 1969:

The photos in the middle tier of the page above show some important Lincoln-Mercury players from this era — from left to right, chief engineer Fred Bloom, chief body engineer Stuart Frey, product planning manager Steve Russell, styling chief Arnott “Buzz” Grisinger, and general manager Matt McLaughlin. (Note that the text misspells Grisinger’s last name, which had only one “S.”)

In the ’50s and ’60s, the phrase “all-new” got a real workout in Detroit marketing copy. From a chassis and structural standpoint, the 1970 Lincoln Continental certainly qualified, but since the three-speed C6 automatic had been used for some time and the 460 engine had first appeared under Lincoln hoods in 1968, the 1970 model wasn’t quite the “completely redesigned, re-engineered car from the wheels up” the text proclaims.

1970 Lincoln Continental Coupé / Ford Motor Company

Back when the 1961 Continental debuted, Lincoln-Mercury had made a big deal of how each car received a 12-mile “final examination” after assembly. The text above notes that this road test would now be conducted “on a computer-programmed road test simulator, which duplicates actual road conditions.”

I realize the black-on-orange of the page above isn’t always the easiest to read (nor was it easy to scan!), so I’ll quote a few pertinent passages:

Probably the biggest news is the fact that the Continental has gone from unit construction to a body/frame chassis. There are several reasons for the change. According to Fred Bloom, chief engineer for Lincoln, body/frame construction cuts down road noise and adds to an improved ride. It’s also more efficient, with better weight distribution, and lastly it cuts costs. The latter point is important because the Continental will now share various underbody and chassis components with other makes in Ford’s stable. Keeping the same unit construction chassis for the past nine years has also created other headaches. Additional steel and sheetmetal were added with each succeeding model without any basic chassis revisions. Consequently, the car kept getting heavier and heavier. Starting fresh for 1970, the Continental will be about 300 pounds lighter, which should cut down on gas bills slightly.

As CC has previously discussed, a perimeter frame is not the same thing as a traditional self-supporting frame like the ladder frames used on larger trucks. With a perimeter frame design, most of the structural strength comes from the body shell, with the frame acting as essentially a full-length subframe whose mass, rubber-isolated body mounts, and designed-in flexibility help to isolate the body and occupants from noise, vibration, and road harshness. Although the body shell must be more rigid than in a vehicle with a self-supporting chassis (where the body is really just along for the ride), using the frame to absorb road shock in this way can allow the body to be lighter than a true unit body providing the same level of isolation. (This depends somewhat on the vehicle’s overall dimensions; a smaller car will usually still be lighter with unit construction.)

Also, because the old Continental was overweight to begin with and had received nine years of belt-and-braces revisions, it could benefit quite a bit by just starting from a fresh sheet of paper, particularly with the growing availability of computerized tools for structural optimization. Those techniques were still primitive compared to modern computer-aided design, but they were vastly more sophisticated than what Ford had had to work with in the late ’50s.

While increasing the big Lincoln’s commonality with cheaper models obviously made sense from a cost standpoint, it’s always a sensitive issue for cars in this class: Nobody buying an expensive luxury car wants to be reminded that it shares many bits and pieces with ordinary family sedans.

1970 Lincoln Continental sedan / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

A potentially bigger issue for buyers was that the new Continental now looked an awful lot like its cheaper Mercury Marquis sibling. Compare the four-door Continental pictured above with this brochure illustration of the 1970 Mercury Marquis Brougham four-door hardtop:

Motor Trend editors were seldom ones to ask troublesome questions, so Sanders skates politely around this point, but Popular Mechanics auto editor Bill Kilpatrick had fewer compunctions: “I can’t make up my mind whether the Mercury is being upgraded to look like the Lincoln or the Lincoln is being downgraded to look like the Mercury,” Kilpatrick wrote in the October 1969 PM. “In any event, there’s a definite resemblance, particularly upfront.” Since Lincoln and Mercury shared the same showrooms, some family resemblance wasn’t totally unreasonable, but it did make the Continental less distinctive than before.

The new three-link rear suspension, which traded semi-elliptical springs for coils and a Panhard rod, was similar to the Mark III, which was largely the same as the 1967 Thunderbird arrangement seen here:

The text claims that there were now “higher rate springs and shocks and a larger diameter roll bar” in front. Motor Trend was right about the stiffer springs — the front spring rate went from 105 lb/inch (at the wheel) in 1969 to 146 lb/inch for 1970 — but the AMA specs show the anti-roll bar as very slightly smaller than in ’69, 0.81 rather than 0.82 inches. The new rear suspension was also stiffer than before, with wheel rate increasing to 149 lb/inch for 1970, compared to just 100 lb/inch for 1969. Surprisingly, this didn’t come at a cost in ride comfort:

On a test drive around the Ford test track at Dearborn, we were quite impressed by the improved handling qualities and ride comfort of the new car. Even on the handling road, with numerous sharp curves, the prototype we drove always kept a tight, flat hold on the surface, with no noticeable wallowing or dipping. Levels of comfort and quietness similar to the Mark III have been a goal of Lincoln engineers, and they’ve succeeded admirably. In fact, the sensation of movement at higher speeds has been reduced to the level of the Mark III. We noticed about a 20-mph difference between our actual speed and our estimated speed at 70 mph on the high-speed test track. This was largely due to the silence and improved ride.

Aside from the stiffer springs and new suspension, another change that probably helped 1970 Continental handling was the increased track width: 1.9 inches greater in front and 3.3 inches greater in back than in ’69.

1970 Lincoln Continental sedan / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

The most interesting new technical feature in the Lincoln line at this time was Sure-Track, an antilock braking system developed by Ford and Kelsey-Hayes. Although it worked only on the rear wheels, this was the first electronic ABS ever offered on a production car, making its debut as a $195.80 option on the 1969 Continental Mark III.

Sure-Track became standard on the Mark III for 1970, but it would still be an extra-cost option for the 1970 Continental. Sanders remarks:

The new system improves braking stability by preventing sustained rear wheel lockup during panic stops, even on ice or snow. Unfortunately, this feature will be an option, and because safety does not sell too well it may be like trying to sell heat lamps in Houston. When we asked why this item wasn’t standard, we got numerous answers. “It would add too much to the base price of the car,” we were told. “There isn’t a sufficient supply to equip all the cars that will be built.” Most of the answers we got weren’t really substantial.

Lincoln offered the rear antilock system through the mid-’70s, but quietly dropped the option later in the decade. My unkind guess is that Ford was reluctant to promote this feature too heavily, lest federal regulators insist that automakers make the system standard equipment across the board!

The 1970 Continental looked bulkier than the ’60s model, but as the comparison table in the right column of the page above reveals, the differences in exterior dimensions amounted to less than an inch in any direction, and there were some modest improvements in interior room, in particular a 2-inch increase in front and rear shoulder room.

1970 Lincoln Continental sedan / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

The rear doors were now hinged at the front rather than the rear — the 1961–1969 Lincoln four-door had only used rear-hinged doors because the original seating “package” (designed for the close-coupled Thunderbird) otherwise made entry and exit very awkward — and the doors themselves were wider. I’m not sure that owners parked next to a 1970 Continental hardtop in a crowded parking lot would have appreciated its 7-inch-wider doors, but it did make it easier for adults to get in and out of the back seat with dignity intact.

You’ll notice that weight is conspicuously missing from the Motor Trend comparison table. Fortunately, I have the 1969 and 1970 AMA specs, which include both base curb weights and the weights of optional equipment. (Since Sure-Track was only available on the Mark III for 1969, I’ve omitted it from this table to allow an apples-to-apples comparison; ordering Sure-Track on a 1970 Continental added 20 lb to the curb weight.)

| Body style | 1969 Base Curb Weight, lb | 1970 Base Curb Weight, lb | 1969 Curb Weight With All Options, lb | 1970 Curb Weight With All Options, lb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-door hardtop coupe | 5,113 | 4,860 | 5,362 | 5,156 |

| Four-door sedan | 5,208 | 4,910 | 5,457 | 5,206 |

As the text explains, the projected performance figures are “calculated by applying estimated improvement factors to 1969 figures.” However, Motor Trend had just tested a ’69 Lincoln Continental sedan in the April 1969 issue, and had found that the 460 engine and optional 3.00 “hi-torque” axle provided strong performance for this class: 0 to 60 mph in 9.0 seconds, the standing quarter mile in 16.2 seconds at 85.7 mph. Therefore, this article’s estimates for the 1970 model — 0 to 60 mph in 8.6 seconds and the standing quarter mile in 16.0 seconds at 86.5 mph with the standard 2.80 axle, slightly quicker with the 3.00 axle — seem perfectly plausible, given the significantly reduced if still hefty curb weight.

Ford 460-4V engine / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

For 1970, the big 460 engine was again rated at 365 hp and 500 lb-ft of torque, both SAE gross. This was the same as in 1969, but the 1970 engine had an air injection system to reduce hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide emissions, which consumed some power — probably something like 6 to 8 hp. I don’t think Ford ever published any net ratings for this engine prior to 1972. (While Chrysler and GM published both gross and net figures for 1971 to prepare buyers for the change to net ratings, Ford apparently did not.)

The 1970 Continental got a revised dashboard with full instrumentation, obviously modeled on the dash of the Mark III. There was also a new Flow-Thru ventilation system, exhausting through a vent under the backlight; Ford had been using flow-through systems like this on other models since 1964.

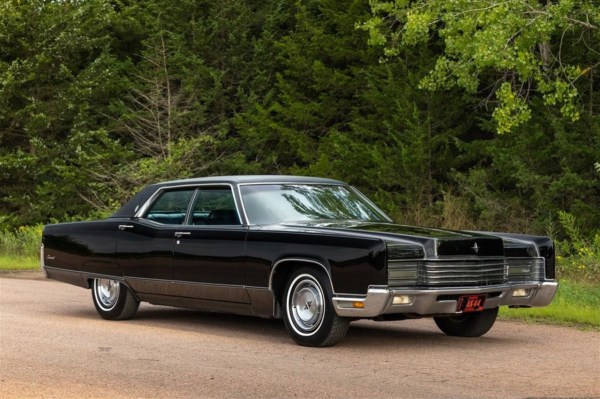

1970 Lincoln Continental sedan, black on black / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

Coolant temperature, oil pressure, and clock / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

Leather-vinyl upholstery was a $157.40 option on the 1970 Continental, but even the standard seats now had latex cushion padding, which Stuart Frey claimed was more comfortable than the usual urethane padding. The text notes that the 1970 model also offered a new radio, “reportedly exclusive in the industry,” with five pushbutton station preselects for both AM and FM. This was a pricey option: $301.70 with power antenna, the equivalent of about $2,553 in 2024 dollars!

Evaporative emissions controls were newly required in California for 1970. This was a somewhat belated move in the emissions control wars, reducing air pollution by capturing and reusing fuel vapors from the carburetor and fuel tank vents, rather than venting them to the atmosphere. Without evaporative controls, a lot full of parked cars on a hot day released a substantial quantity of hydrocarbon emissions, even if their engines were never started. Federal emissions regulations would require the same controls for 49-state cars starting in 1971.

1970 Continental had concealed headlamps / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

The giant awakens / Frankman Motor Company via ClassicCars.com

I’ve never been a big fan of the 1961 Continental, and its numerous facelifts didn’t improve its looks, but it’d be hard to deny that the 1970 Continental looked less special. It was a better car in many respects, and weight reductions of 200 to 300 lb are nothing to sneer at even in land yachts like these, but whether the 1970 model was worth almost $2,000 more than a similar-looking Mercury Marquis Brougham was harder to say. Since Continental production fell from 38,383 in 1969 to 31,695 for the all-new 1970 and 35,551 for the 1971, it seems that buyers struggled with that same question. The Mark III cost over $1,000 more than the Continental, but sold nearly as well, and rated higher in prestige.

The big Lincoln sedans would yet have their day, but in 1970, it seems that simply being better wasn’t quite good enough.

Related Reading

Curbside Classic: 1970 Lincoln Continental Coupe – Hot Rod Lincoln (by Paul N)

Curbside Classic: 1969 Lincoln Continental – Missed It By THAT Much (by J P Cavanaugh)

Curbside Classic: 1968-1971 Lincoln Continental Mark III – Right On!…The Mark (by Paul N)

Vintage Motor Trend Review: 1969 Cadillac Coupe de Ville, Lincoln Continental, Imperial – American Luxury Comparison (by Rich Baron)

Vintage Car Life Road Test: 1961 Lincoln Continental Sedan – “The Best-Looking American Car Built Today” (by Paul N)

I had one.

It was in perfect shape at 9 years old, burned no oil.

I gladly put up with the monthly Ford parts install (I worked in an equipment shop) but sold it when gas hit $1.00.

It handled better than you think. Ask Richard Nixon.

Although the 61 Continental was widely celebrated, IMO it was TOO small and lacking the OTT chromed image of a LAND YACHT. The 70 revision was a step in the right direction 👏. Eventually Continental would grow back to the gargantuan LAND YACHTS as befitting a true Luxury CAR. I’ve been fortunate to own 78 Town Coupe, 89 Town Car Signature, and current 2007 Signature Limited , as well as several GRAND MARQUIS. Loved them all. Wish I still had the 78. It’s HUGE! It guzzles gas! It pollutes the air! It scares the birds! Other cars part like the Red Sea to get out of the way! What’s NOT to love? 😉 . My current Town Car is the last gasp of traditional American Luxury CARS. Sad to see what Lincoln produces. Glorified trucks, masquerading as Luxury vehicles. 🤮

For whatever reason, these always looked a lot larger – to me at least – then the predecessor model. I liked the dashboards and the ribbon speedometer. I think it was probably one of the last of the changing color ribbon strip speedos. White until 70, red above 70. A neat 50s feature in a 70s auto.

One of the few cars where fender skirts don’t bother.

That the outgoing 9 year old model outsold this redesign, and not like in a bad economy or the gas crisis, kind of says everything about how this missed the mark.

Also that straight on the front shot from the end makes that car look so bad with the bent grill bars. The seller couldn’t straighten that out a bit?

1970 was a a year of mild recession, although that didn’t seem to hamper Cadillac. Or the Mark III, for that matter.

I have long been conflicted about the 1970-71 Lincoln. I have concluded that the styling was a little too massive, a little too generic, and even a little ham-fisted – a rare miss for Ford of that time. The changes to the beltline (via new rear doors) and a change in the grille texture for 1972 fixed what I saw as wrong. The buying public seems to have agreed.

One area where this car diverged from the LTD/Marquis was in rustproofing. The big Fords and Mercuries were terrible, terrible rusters while the Lincoln was quite rust resistant for its time.

I really enjoyed this. I had always assumed that the ’70 redesign resulted in a much bigger and heavier car. Not only was it only fractionally bigger in every direction, it was also lighter and with a bit more interior room. The similarities to the Mercury as depicted in the ad featured say a lot. I thought the ’61 was / is stunning, but learning more about the 1970 through this article makes me respect it a bit more.

And I love those rounded square gauges!

Yes me too! The gauges are beautiful.

I don’t know what it was, but Lincolns in this era, 1970, seemed to rust away fast

I owned a 73 Continental coupe, I thought it was a magnificent car. It was gigantic, comfortable, easy to drive, and a real attention magnet in 1993 when I had it. I traded a 78 c10 and 300 dollars for it. My wife hated the car, but I loved it. It met it’s end when I hit the back of a semi truck that stopped faster than I could. Front end and right front fender damage was all it suffered, but pre internet made parts finding next to impossible. I sold the car for a thousand dollars, that guy drove it for a year or two before he sold it. The last time I saw it, it was rocketing down the expressway with two younger Mexican guys in it, never saw it again.

Rear suspension diagram is nothing unique to Lincoln. My 67 Parklane has the exact same setup. No doubt all large FoMoCo cars did back then in a certain time frame.

Well, no, because that diagram is a press image from the debut of the 1967 Thunderbird.

Thank you for the comparison between the new 1970 versus the outgoing 1969 models. I long suspected the newer car might be slightly less heavy, given the structural supports present in the 1960s models. That ‘70 was only marginally larger is also a surprise.

Ever in tune with the times, no less a fashionable executive than Roger Sterling, Don Draper’s boss, drove a 1970 Continental in the “Mad Men” episode when he and his ex-wife drive Upstate and unsuccessfully attempt to rescue their wayward daughter from a hippie commune. I thought the car as a newly introduced model was cast well as something an affluent couple in late middle age would choose over the rather dated 1970 Cadillac. Given Cadillac’s downward trajectory in prestige in the 1970s, if not in sales, and Lincon’s upward momentum, Roger may have been characteristically ahead of the curve.

Roger’s car was a 1969 model.

Timely. I’m just rewatching MadMen on Netflix. Halfway through S 1.

Roger is a fascinating character. Such a dry wit.

As to how “new” this car was, everything tells me that it was of course very heavily based on the Ford and Mercury. Certainly the chassis, with certain changes of course. I wonder just how far the under skin similarities go? Same critical cowl pressing? Same windshield even?

Nothing wrong with any of that; it’s straight out of the GM and Chrysler playbook.

All of that was quite apparent to my eyes at the time, and it made it seem like a come-down, especially with the Mercury’s styling looking so similar.

A different car for a different time. 61 Continental = Kennedy, 70 Continental = Nixon. Both have their strengths both have their weaknesses. The world never stops turning.

At the time, I knew one family with a ‘70 Lincoln, and another with the big Mercury. My impression as a 9 year old kid was not so much that the Mercury made the Lincoln look cheap — it was still a big, expensive looking car— but more that Mercury had really moved up a class. But that’s neither here nor there. Either way, it wasn’t an ideal marketing situation for Lincoln.

Regarding Ford’s lack of promotion for the Sure Track two wheel antilock brakes, I wonder if they were a little intimidated by Chrysler’s four wheel antilock Sure Brake (I think that’s what it was called) system. You could easily imagine Chrysler claiming their system was twice as good!

Well, (a) Sure-Track preceded the Chrysler-Bendix Sure-Brake system by about two years, and Lincoln-Mercury didn’t do a lot to promote it in that interval, and (b) Chrysler didn’t really promote Sure-Brake very much either, and they certainly didn’t pitch it in comparison to the Kelsey-Hayes systems. I think the reason is more that while it was obviously a safety feature, advertising it that way would draw attention to the fact that it was generally an extra-cost option, not standard equipment, so observers (in particular federal safety regulators) might have said, “If it’s so much better than your regular brakes, why isn’t it standard on all your cars?”

Is it just me, but you really dont get too see too many of them around anymore.Aside from one (a `71 ) that I saw at a car show I can honestly say I haven`t seen one in many years.

I’ll take one of these early ones over the overwrought ’75-’79 models any day.

Cleaner styling and more power. As for one of those later 400 powered ones, no thanks!

AFAIK, the earliest TV product placement for the 1970 was the TV movie pilot for Cannon.

It was promptly wrecked. When the TV show was picked up, they switched him into a Mark III.

Did you know, that William Conrad (alias Cannon) was born John William Cann ?

Cann % Cannon – you get it ?

I doubt the 2.80 axle car could accelerate faster than the 3.0 version, but it should have a higher top speed. The weight difference is pretty small.

Didn’t Lincoln make A/C standard in ’70, or was it ’71? That would have been the heaviest option is it wasn’t standard.

How is a weight difference of 250 to 300 lb “pretty small”? As a percentage of total curb weight, I guess, but it’s enough to account for a 0.2-second improvement in quarter mile ET. The point was that Lincoln engineers said the lighter 1970 model with 2.80 axle was a bit quicker than the heavier 1969 model with the 3.00 axle, with the lighter 1970 model with the 3.00 axle being the quickest of the bunch by a small margin.

Air conditioning was not standard in 1969 or 1970; it became standard on the Continental in 1971. Therefore, it’s reflected in the “curb weight with all options” columns in the weight comparison tables, not in the “base curb weight” columns.

The grille and headlights are of course different, and the chisel tips are blunted, but the head-on front view is remarkably similar to the ’69-70 Cadillac. Both of these and the fuselage Mopars appear bulkier than their predecessors by raising the fender lines. Wonder who had that idea first and how it was passed around. Spies! Loose lips!

I admired the ’61 Continental, but it seemed to me that this generation of Continentals (’61-’69) peaked in terms of style, with the face-lifted ’66 model. The styling tweaks of the ’68 and ’69 models were obviously just change for the sake of change, things to make the cars look different from the previous models and unimpressive. For some reason the “classic” ’61-’69 never seemed very popular in my neck of the woods and I don’t recall seeing very many of them when I was kid in the ’60s. (The Continental Mark III and later Mark IV seemed reasonably popular.)

I recall being unimpressed with the ’70 model, but it really didn’t seem all that Marquis-like to me until the restyled ’71 Marquis came along with its fender skirts. Out of the ’70-’79 models, I liked the ’72 and ’73 models the best with their egg crate style grills (and the little egg crate style grills on the headlamp covers). It seemed to me that it was with the ’72 models that Lincoln Continental sales started picking up and I started noticing more of them around.

Was their either a Folding Hardtop Sedan or Convertible version of this car ?

Wiki says NO.

But their was a Convertible in a Patricia Arquette & Michael Madsen film called “Trouble Bound”.

I had a 1970 sedan in the early 1980’s, enjoyed it very much in terms of driving and ride qualities. It was good for only 10 mpg no matter how one drove it, but did get up and go quickly when commanded. While leather interior durability and quality were better than those in the slab-side 1960’s models, the plastic armrest and various other parts were rather breakable and hard to replace, did seem cheapened.

I was bummed about the change from the clam-shell doors when the 1970’s appeared but did appreciate their ease of ingress/egress. I had a 1963 convertible later, noted that aspect wasn’t a strong suite especially to the rear seat. I was also unhappy they didn’t at least include a two-door convertible but didn’t realize that era was ending. The Andy Hotton convertible conversions also with other aftermarket coachbuilders took care of that demand.

Yes, less distinctive than the 1960’s ‘classics’ but now far more affordable in good condition when one is found now. More comparable to their contemporary Cadillac and Imperial, one has to take the Lincoln for what it is, not for what one wishes it was.

‘Buzz’ Grisinger, in an interview in Continental Comments, the Lincoln Continental Owners Club magazine, admitted the benchmark car which influenced the styling were the 1967-’68 Buick Electra 225s. It can be especially seen in the body architecture through passenger compartment and rear quarter/deck treatment. Derivative but pleasantly so.

The 1970 Lincoln Continental sedan is one car which I owned prior I would enjoy having another copy if found in good condition and reasonably priced.