1951 Kenworth powered by Hall-Scott 600 hp OHC hemi V-12 – The Ferrari of Trucks

1951 Kenworth powered by Hall-Scott 600 hp OHC hemi V-12 – The Ferrari of Trucks

Once upon a time there was a builder of large spark-ignition engines that stood (hemi)head and shoulders above the rest. These engines were legendary for their massive torque and horsepower, thanks to their free-breathing overhead-cam cylinder heads. They instilled pride in their owners and drivers, in the knowledge that their vehicles were powered by the most powerful, fastest and best-built engines available.

E.J. Hall was a young man besotted with the quest for speed and power at the dawn of the automotive era. He unlocked the secrets of extracting higher power from engines early on, and applied them to a wide range of applications. His exacting standards for engineering, design, materials and workmanship resulted in engines that were not just more powerful, but also had legendary durability and reliability, and even looked and sounded better than any others. No wonder the myth of Hall-Scott engines endures, even after its protracted decline and ignoble death over fifty years ago.

Elbert Hall (r) in the 1904 Heine-Velox

Elbert Hall (r) in the 1904 Heine-Velox

Elbert J. Hall was born in the future Silicon Valley, in San Jose, CA. in 1882. As a boy he spent hours doodling engines and other mechanical devices, and building models of them. The internal combustion gasoline engine had been invented only a few years before his birth, and they had their grip on his mind and imagination as on so many others at the time. As a 17-year old, he got a job fixing irrigation pump engines for a local farmer; he so excelled at it that the distributor of these crude Atlas engines hired him away. It’s a classic Silicon Valley story, but with a different high-tech.

In addition to servicing engines for his new employer, Hall also began to design gasoline engines as well as improving existing ones, in order to make the crude cars of the time more powerful, able to take on the steepest hills of San Francisco as well as competitors at the race tracks.

Hall moved on to the Heine-Velox company, where he is credited with assisting in the design of the advanced ohv engine in their new 1904-1905 car, which quickly acquired a reputation for being exceptionally fast. But that venture was cut short by the 1906 earthquake.

After several various other short stints, Hall became involved with the Sunset, another Bay Area car with a rep for speed. On the side, he began to build his own car, the Comet, starting in 1908. Only a small number of Comets were ever built, and after the firm went out of business, Hall opened his own shop—Hall’s Auto Repair—in San Francisco, where he also continued to build a few new second-generation Comets.

The Comet’s key feature was not its chassis or body, but its engines, with advanced overhead valve heads to optimize their breathing, significantly better than the typical side valve (flathead) engines of the time. Most Comets four cylinders, but he also built some sixes and one or more very potent V8s, at a time when that configuration was almost unheard of. Only a handful of automobile V8 engines had ever been built prior to the Comet’s V8; all of three by Rolls-Royce in 1905, and one or more in the 1907 Hewitt. Hall was a V8 pioneer, and Cadillac would carefully examine his Comet V8 prior to building their first V8 in 1915. Ironically, Hall-Scott did not build any production V8s, except for a few early aviation engines. All of the later classic Hall-Scott engines were inline sixes or V12s.

Halls’ 420 cubic inch Comet V8 produced up to 80 hp, a prodigious amount in 1908, which soon made it legendary on the West Coast. But even the four cylinder Comets quickly became the dominant cars in the dirt track races of California, with some organizers going so far as to ban Comets from their tracks.

Hall claimed that the four cylinder Comet could reach 45 mph from a standstill driving up three blocks of San Francisco’s steep Powell Street, and guaranteed that every Comet could reach 75 mph. The ad above makes a bold claim, although with a small-print qualifier. Nevertheless, only a small number of Comets were built. The number of car makers was exploding; there were some 515 at the time, and 1908 was also the year Henry Ford introduced his Model T. The days of hand building cars out of one’s garage were ending, and quickly.

In 1908, Hall was 26 and ready to conquer new horizons. In that year he met Bert C. Scott, who came from a wealthy Bay Area family and was clearly headed into a career in business. Hall had given Scott a very brisk ride in his Comet, resulting in a sale to him as well as to two of his friends. Scott soon took the Comet to the race tracks, and in recognition of Hall’s talents, a partnership budded.

Rail Motor Cars

Scott’s father was associated with the Yreka railroad, which operated a McKeen railcar, a pioneering gas-powered self-propelled unit designed to replace steam on lightly used routes. The McKeen was slow and unable to pull anything but one small, light passenger car. Its engine was mounted directly on the leading truck and had only one gear and chain drive to just one of the axles.

Scott had the idea that a more powerful motor car able to haul several coaches and/or freight cars would be highly advantageous on the many smaller lines to replace steam. Scott invited Hall to create a partnership to build just such a car.

Hall had to substantially scale up his engine design brief, and created a new 8 x 10 (bore and stroke in inches) design that could be built in four, six and eight cylinder versions, with 2,010, 3,014 and 4,019 cubic inches, respectively.

Hall had the engines mounted inside the cab of the car, with its power flowing through an automotive-type clutch, a four-speed transmission and then via drive shafts to both axles in the leading truck. This resulted in better traction, a wider range of speeds, the ability to better handle grades as well to be able to operate in either direction in all four gears, reducing or eliminating the need to turn the motor car around at the end of the line.

A firm order for one from the Yreka RR got the new venture rolling, with the Holman Co. in SF building the frame and wooden body while Hall built the engine and running gear in his shop. The car operated successfully, and the two men formed the Hall-Scott Motor Car Company in 1910.

Land and buildings were bought at 5th Street and Snyder Avenue (later renamed Heinz Ave.) in West Berkeley, where H-S would build its legendary engines for the next 48 years in a plant that eventually covered 13 acres. One of the main advantages of this location was the proximity to Macaulay Foundry, which would produce all the high-quality aluminum, steel and iron castings for H-S engines.

Hall-Scott built rail cars for the next eleven years; it turned out to be a rather modest-sized market, but it was just enough to establish the firm and give it a basis for expanding into other areas where Hall could put his engine designing and building skills to good use.

Here’s a video of an H-S rail car engine in a museum. It’s running, but unfortunately it’s just idling with no load on it, so we can’t experience what they sounded like when working hard pulling a train. It’s a common shortcoming of these types of videos; engines sound best when they’re under a load.

Aviation Engines

Aviation was of course the really hot new thing at the time, and Hall was naturally drawn to it, as the requirements for high output and light weight were natural to him. Right from the founding of H-S, aviation engines were part of the brief, and would become the mainstay product for most of the 1910s. Hall developed a modular family of engines that shared many parts and design principles, starting with the four cylinder A-1. It had a 4″ bore and 5″ stroke for 251 cubic inches, and was rated at 32 or 40 hp, depending on the governed engine speed.

To attain the required lightness (165 lbs), the individual cast iron cylinders (with integral heads) were bolted to the aluminum crankcase and had pressed-on steel jackets for water passages. In addition to the four, there were three V8 versions, with varying bores and strokes, making up to 100 hp for the largest 785.5 cubic inch version.

The aviation engine field quickly became crowded too, with 25 firms trying to make a go of it at the time. H-S would need stand out in order to succeed, one of the key factors being the intrinsic superior breathing and resultant torque of their overhead valve design. H-S aviation engines quickly proved themselves able to fulfill the expectations of their designer and their owners, winning numerous prizes and awards. As the highest power engine available at the time, the 100 hp V8 found buyers among barnstormers and others looking for maximum speed, climb and reliability.H-S became known as the best-known aviation engine maker behind Curtiss.

It would be interesting to determine just how much influence Ferdinand Porsche’s seminal 1910 Austro-Daimler D-6 aviation engine (above) had on E.J. Hall. Porsche’s D-6 is almost universally considered to be the single most influential aviation engine, with its high power output thanks to its hemi-head, whose valve were operated by pushrods and a single rocker that operated both valves, due to the cam operating in both directions (up and down). The D-6 greatly influenced the famous Mercedes aviation engine—which added an overhead cam—as well as others throughout Europe at the beginning of WW1.

The next generation of H-S aviation engines, starting with the A-5 in 1915, also now sported an overhead cam and canted valves in a hemi-head. configuration. Undoubtedly Hall was aware of the growing dominance of this design in European aviation and racing car engines. Of course there were some very early pioneering American hemi engines too, including the 1905 Premier, which also had an overhead cam. In fact, there’s some good evidence to suggest that the hemispherical combustion chamber with canted valves was first conceived in the US in 1901 or earlier.

The A-5 (and four cylinder A7) thus set the basic formula for almost every Hall-Scott engine to come, with its hemi-head, shaft-driven overhead cam, and other details. It also was the first H-S engine to have a 5″ by 7″ bore and stroke, one that would be used on a number of subsequent H-S engines for many decades to come. It was also the first to have the cooling passages in the cylinders cast integrally, instead of the pressed-in jackets. This improved reliability at a small expense of weight. Weighing 525 lbs, displacing 824.7 cubic inches, the A-5 produced 125 hp, for a very favorable power-to-weight ratio for the times.

A somewhat larger A-5a, and four cylinder versions (A7/A7a) followed, which were the first American aviation engines to use light weight aluminum pistons, on a design patented by Hall. The A5 and its variants quickly became considered the premier aviation engine, and sales took off.

If you want to hear what these motors sounded like, here’s video of a Fokker D.VII powered by a six cylinder A5 (starting at 1:00).

Several of these Hall-Scott aviation engines have been retrofitted into early racing-sports cars of the era, as they are somewhat more available than the originals, such as this former Peugeot Indy 500 competitor that now has a four cylinder A7. There’s others out there too.

In 1917, H-S built their first V12, the A-8. Conservatively rated at 300 hp, some reports indicated it was capable of 450-500 hp. The timing was fortuitous, as the US was about to enter WW1, and the A-8 played a significant role, just not the obvious one, as it never got built. But it did sire one of the greatest engines ever, the Liberty.

The Liberty Engine: Greatness and Controversy

In 1917, the Aircraft Production Board summoned Packard chief engineer Jesse G. Vincent and Elbert J. Hall, and put them together in a suite in the Willard Hotel in Washington, and told not to come out until they had a set of drawings for a high performance airplane engine. This happened just months after Hall Scott released its new A-8 V12 aircraft engine, designed specifically by Hall for combat aircraft, and capable of 450 hp. When Hall was called to Washington to be sequestered with Packard’s Vincent to design the Liberty, Hall put service to the country ahead of his personal and company’s interests, and the A-8 was thus stillborn.

Why the A-8 was not adopted and why Packard’s Vincent was asked to join in creating a new engine is a contentious question that has never been fully answered, but politics was clearly the most obvious one. Vincent was a well-know figure and good at self-promotion, and of course Packard was at the height of their power and image. Hall was quite different; a brilliant but soft-spoken engineer who felt that his designs and products spoke most eloquently for him.

Vincent claimed that Packard had been developing a high output aviation engine for some time. Up to this time, all Packard engines had been relatively conservative cast iron side valve engines, suitable for their large cars and trucks, but certainly not for airplanes.

The resulting Liberty V12 design (rated at 400 hp) had most of the basic design characteristics of the H-S A-8 V12, such as the two-piece aluminum crankcase, individual steel cylinders with a brazed-on water jacket, and of course the overhead cams and “free-breathing” aluminum hemi heads. The one curious change was from the A-8’s cylinder bank angle of 60 degrees to 45 degrees, one that inherently increased vibration. A number of actual H-S A-8 parts were used in the building of the prototype.

Most of the changes were for ease of mass production. That’s possibly the most important input Vincent was able to provide, since Hall had been designing and building OHC hemi engines since 1910, and was known to have more knowledge about their “deep breathing” qualities than just about any other American engine aviation engine designer.

Since Packard (and others) had the large production facilities to build the Liberty in large quantities, H-S was not given any of the production contract. H-S did build as many of their smaller four and six cylinder engines during the war as possible, and enjoyed record profits for a fairly small firm.

Although the Liberty engine was built in great numbers by Packard, GM and others, it arrived too late to be used in the war, except for a few American versions of the British Airco DH4. But it saw widespread adoption in the post war years, in all manner of civilian and military planes as well as in tanks and boats. It was eventually succeeded by the Packard 1A-2500 V12 engine, which was also used in aviation applications, but most famously in WW2 PT boats. The Liberty engine became iconic, representing America’s ability to build high power engines in mass production, a preview of what would become widespread in WW2. Ironically, it was also what lead to the eventual demise of H-S.

Vincent and Packard hogged all of the publicity, for decades to come, sometimes in ways that were misleading or just untruthful. Vincent was a natural self-promoter whereas Hall was more self-effacing.

But H-S did fight back, with a PR campaign to give credit to the many profound similarities between the H-S A-8 and the Liberty, and Hall’s key role in that. H-S made references to their engines being of the “Liberty Type” for a number of years, and the next series of engines were the “L-Series”, undoubtedly referring to the Liberty.

Hall-Scott actually took advantage of the Liberty program, by buying stocks of surplus parts such as steel cylinders (made by Ford) and other parts and utilizing them in their post war L-4 and L-6 engines. These became the standard engine in the US training airplanes in the early 1920s, as well as other applications, some of which involved setting new records for distance. The twin vertical radiators are visible to the sides and rear of the engine here.

At the end of the 1910s, it might have been natural to assume that H-S would continue to be a force in both aviation engines and rail cars, but things turned out rather differently.

Post War Diversification

The glut of cheap surplus Liberty engines put a damper on the aviation engine sector after WW1, and the rail car market never amounted to much anyway, so H-S looked to other fields to put E.J. Hall’s fertile mind to good use. Hall continued to tinker with racing engines, and his shop was a destination for a number of West Coast racers for improvements and special parts. Installing his high-power aviation engines into cars for racing or just fast road use was a specialty.

In 1916 Hall made plans build a race car for the 1917 Vanderbilt Cup Race, using one of his 9.9 L A7a aviation fours in a Reo frame and transmission. He never got around to it, but Californian Dick DeLuna reconstructed it in recent years from original drawings, using authentic vintage components. The build took 5½ years to complete. The engine produces some 100 horsepower at 1,300 rpm and a whopping 450 ft.lbs. of torque (the same as a Dodge Viper) which is transmitted to the rear wheels via a modified Reo transmission. Top speed is estimated to be in excess of 100 mph.

There’s one or two videos of it, but once again, only while idling and not at speed.

A major new product line for Hall-Scott was the Ruckstell two-speed axle for the Ford Model T. Hall knew Capt. Glover Ruckstell from the Air Service, and Ruckstell found himself at H-S after the war. A fan of racing and speed, Ruckstell brought the concept of the two-speed axle to H-S, where it was perfected and built, and quite profitably at that. The Ruckstell made the T significantly sprightlier, giving it four speeds instead of two. It was widely used in the various speedster and racing versions of the T, as well as for regular folks wanting more. There was also a truck version which gave considerably more versatility to the Model TT truck. Up to 600-800 units per day were built at H-S during the heyday of the Ruckstell axle.

Hall also had a number of contracts with GM and Ford, designing and developing prototype components for possible production. For Buick, he designed a new engine and rear axle in 1922, but his relationship with Ford was more fruitful, and covered a wide range of projects. One of the more fascinating ones was an experimental six cylinder engine for the Model T, commissioned in 1924 by Henry Ford. It was the only side-valve engine Hall ever built, at Ford’s insistence. The 212 cubic inch “Little Six” was too long to fit in the T’s front end, and Ford eventually went with a V8 engine in 1932.

Hall also built several gasoline-powered rail cars for Ford, which used underfloor horizontal version of the four and eight cylinder A5/A7 engine. Although nothing became of these, the horizontal underfloor engine would become a significant product line for H-S bus engines in the future. Harry Miller also consulted with Hall on a number of aspects and details of the high performance racing engines Miller was building in the 1920s.

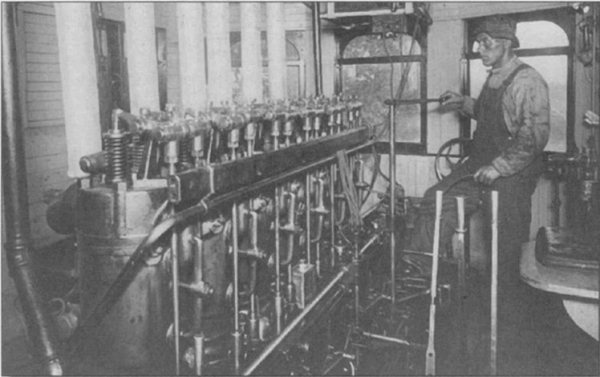

In 1926, Hall-Scott received a contract to design and build a new heavy duty four cylinder truck engine for International. This engine pioneered most of the features of subsequent H-S truck, bus and industrial engines to come. That included “unit construction”, involving a separate cylinder block mounted to the crankcase, the overhead cam cylinder head, and other details. This allowed servicing or replacing the head or cylinders without removing the engine or taking the crankcase apart.

These engines gave excellent service in International trucks, including a large fleet of them used in the building of Hoover Dam. H-S was able to sell them to other truck makers after its exclusive arrangement with International was satisfied. It was also repurposed into the long-lived “Fisher Jr.” marine engine as well as the Model P-167 industrial power unit.

Although H-S stopped building complete rail cars after 1921, it did develop a new large engine suitable for use in that application as well as marine and various stationary ones. This was the Model 350, an 8 x 10 (bore and stroke) six with 2386 cubic inches that was rated at 424 hp @1200 rpm and a whopping 1965 lb.ft. of torque @1000 rpm. The 350 had all the hallmarks of classic H-S engine design, just on a larger scale. The 350 and its offshoots would be the most powerful engines offered by H-S until 1937.

These engines were designed to power gas-electric locomotives and rail cars, unlike the mechanical transmission of the older H-S rail cars. GE offered the 350 in conjunction with its generator and other components for locomotives and rail cars. But the gasoline engine in this application was a dead end, as the diesel engine was in its ascendancy on the rails. In a foreshadowing of what would impact H-S engines in other applications, the significantly more efficient diesel engine soon made Hall-Scott’s rail engine business irrelevant, and the company spent no more money in this field.

GM’s Winton/EMD unit jumped into the diesel locomotive propulsion market, and quickly established a dominant market position. Alco and GE soon followed. This required massive investments, the kind that H-S would have been unable to muster even if they had wanted to.

Instead, H-S focused on the truck, bus, tractor and industrial engine market, one which was predicted to experience very rapid growth and one where a smaller firm like H-S could hope to compete successfully. The great majority of truck and bus makers of the time were “assemblers”, and typically offered a variety of power plants and other drive train and chassis components from various suppliers.

That’s not to say it wasn’t already a crowded field: Waukesha, Buda, Continental, Hercules, Herschell-Spillman, Hinkley, Le Roi, Lycoming, and Wisconsin were all pursuing the same market fo engines. Given its location in the West Coast at a time when the industry was very regional, the obvious customers were going to also be located in the West.

Holt Manufacturing Company (soon to become Caterpillar), the pioneer in tracked farm and industrial vehicles ,was located in Stockton, CA., and was in need of a engine for its new smaller T-35 tractor. This was considerably smaller than previous Holts, and was intended to make crawler tractors much more accessible for farming and other applications.

The MS-35 engine that E.J.Holt designed in 28 days was a 276.5 cubic inch four, making 25 hp at a low governed speed of 1000 rpm. It too featured the customary Hall overhead camshaft and hemispherical cylinder head.

Hall’s work with Holt led to a relationship with Berkeley-based Fageol Motors, a very innovative company led by the two Fageol brothers and Louis Bill. They produced trucks, buses, tractors, and a few very high-end cars in Oakland and Kent, Ohio. One of the wilder products involving Fageol and H-S was the Fageol car, first built in 1917 and utilizing a 125 hp, 825 cubic inch H-S A-5 six cylinder aviation engine.

This was likely the fastest road car at the time, but its astronomic price of $9,500 for a bare chassis and $12,000 for a fully equipped car resulted in very few ever being made. Its ability to roar up the steepest California mountain grades at unsurpassed speed made it the first “supercar” and a legend, even if not a well-known one. The Fageol was essentially a preview of the Duesenberg Model J to come.

The Fageol Safety Coach had a much wider impact and market. This was a radical design at the time (1924), with a drastically lower center of gravity than all other coaches then, which sat high on the narrow and tall truck chassis upon which they were built. The Safety Coach was the first bus designed specifically for the application, and ushered in greater, speed, comfort and of course safety, with its low center of gravity, wide track, and superior suspension and brakes.

Fageol approached Hall for a suitable engine, the result being a modified version of the Holt tractor engine, but with larger displacement and making some 55-62 hp at a much higher 1800 rpm, which yielded a top speed of 36 mph. That may sound ridiculous to us today, but that was then an improvement, and its superior road holding allowed higher average speeds between stops. Drivers, passengers and operators were all very happy. The Safety Bus sold well, and Fageol opened an Ohio plant specifically to supply customers in the eastern half of the country. A larger 29 passenger version used a six cylinder variant, the HSF-6.

The HSF engines were widely praised for their durability, thanks to the use of only the very highest quality materials, fabrication, assembly and testing. Every detail, down to the blades of the cooling fan, were of obviously higher quality than average. It was these details, so essential in aviation engines, that cemented the reputation of earthbound Hall-Scott engines.

Fageol would use various H-S engines in their trucks and buses for some years to come. Fageol eventually went out of business and their truck line and California plant was bought in 1939 by Peterbilt.

H-S also decided to compete in the crowded marine engine field. The LM-4 and LM-6 (“L” for Liberty) were an evolution of their war era engines, with certain differences to make them more suitable for marine applications. These engines, with their high outputs, made a name for themselves in racing, winning numerous events. A smaller series, the HSR, was based on the Fageol bus engines.

Acquisition by ACF

In 1925, H-S was bought by American Car and Foundry (ACF), a large maker of railroad cars seeking to diversify into trucks, buses, and the engines to power them. ACF also bought Brill, a bus maker, as well as the West Coast division of Fageol. Bert Scott became a director at ACF, and E.J.Hall was named V.P. of Engineering, but would not be staying for long. Hall-Scott saw this sale as a way to both capitalize on its growing success as well as to seek safety under a large corporate umbrella.

In addition to the existing Fageol bus line, ACF and Fageol expanded into gas-electric buses, which were attractive for urban transit operation since it eliminated all of the endless shifting. Eventually automatic transmissions made this system obsolete.

ACF also introduced a new snub-nosed coach, the Metropolitan, targeting urban transit, and looking not wholly unlike the streetcars that ACF also built. It was a pioneer, and H-S engines were mounted low under floor, just ahead of the rear wheels.

Later versions had the engine tipped 90 degrees to its side, the first of many such underfloor H-S engines. These were not boxer engines, but existing inline sixes modified to lay on their sides. The modifications were pretty extensive, including a dry sump system for the oil, among others.

These engines, including the related upright Model 175, had hp ratings of up to 211 hp, and over 600 lb.ft. of torque, both significantly higher than typical at the time, and further burnished the Hall-Scott image of superior power for trucks, buses, and other applications.

There was of course a downside to being a division of ACF, as sales to competing bus manufacturers was restricted; only Kenworth and Wentworth buses used H-S engines at this time. That would change later.

Hall-Scott was also a pioneer in offering versions to burn various forms of LPG: propane, butane and various mixes of them. These fuels were widely available in the West at significantly lower cost. It was something of an alternative to a diesel, reducing fuel cost while maintaining high power levels.

The Invader

Although the market for larger commercially-oriented marine engines was moving rapidly to diesels, there was a growing market for smaller but powerful gasoline engines. With the resources of ACF, Hall-Scott developed a new engine that would become its best known and loved engine (in its Model 400 variant), one that was built for 23 years: the Invader.

Designed for use in cruiser, water taxis, scout boats and other personal and light commercial boats, the Invader delivered 250-275 hp from its 997.8 cubic inch six cylinder engine. Not only was a superbly reliable and powerful engine, it also looked the part of a premium product, with its polished alloy valve cover and other parts.

Invaders were commonly installed in multiples, including four of them in this 1935 boat, enabling speeds of 45 mph. And a very lovely exhaust note to accompany that.

Introducing the Invader in 1931, at the height of the Depression, was challenging to say the least, but there were still enough wealthy folks who wanted the latest fast boat, enough one to keep the lights on at Hall-Scott during those difficult years. Prohibition made Invader-powered boats highly desirable “rum-runners”. And the Coast Guard bought them for their new picket-boat patrol craft.

The Invader is arguably Hall-Scott’s single most important engine, not just because of its long successful life on the water, but also because off the offshoots: the V12 Defender and the Model 400, a family of truck and industrial engines that became the mainstay of the company’s land-based products. The rest of Hall-Scott’s years in business were mostly based on the success of these offshoots of the Invader.

Not coincidentally, the Invader was the last engine to be designed by E.J.Hall, as he left the company in about 1930. He then partnered with Norman de Vaux in De Vaux – Hall Motors to build a new low-priced automobile, the De Vaux 6-75. The assumption at the time (1930) was that the depression was mostly over; that tuned out to be wrong, and the company quickly went bankrupt.

The US Navy was also an enthusiastic buyer of Invaders, but was angling for something even more powerful. With Hall gone, the H-S engineering staff resorted to the obvious solution within their capabilities: make a V12 version, which was called the Defender.

Displacing 1996 cubic inches and weighing some two tons, the Defender initially packed a 575 hp punch. When the Navy wanted even more power, the displacement was upped to 2281 cubic inches, now making some 630 hp. There was more to come yet, in the Defender’s power portfolio.

World War II

As for so many companies struggling at the end of the thirties, the war offered a reprieve for H-S, as it essentially guaranteed profits from military contracts. Only two engine types were built during the war years: the six-cylinder Invader, the V12 Defender and the Model 400 truck engine (more on that below), which was based on the Invader.

The powerful 400 was put to good use in the M 26 armored tank and heavy vehicle retriever. The Army did not want to deal with the logistics of having two kinds of fuel , so it stuck almost exclusively to gas powered vehicles. Thus the Model 400 was ideal for the needs of the very heavy M 26, as well as the experimental and larger twin-engine T-8.

The Navy was eager to leave gasoline behind, for a number of good reasons. Diesel powered boats and ships had longer range and required fewer refueling support. Safety was a very big issue, as volatile gasoline fumes that settled in the hulls and engine compartment floors were a huge fire hazard. That alone was a compelling reason for switching to diesel.

But the Navy realized that for certain missions, gas engines’ superior power output and lower weight could not be matched by the diesels of the day. Thus the V12 Defender found itself in the hulls of many smaller navy ships, often in multiples. To meet the demand for even more power, Hall-Scott added superchargers to the Defender, upping its power to almost 1000 hp.

Hall-Scott could not meet the Navy’s demand for engines, so Hudson was picked to build Invaders under a license. There were some minor differences, mainly in the cooling system, but Hudson made sure that its name was prominent on each one. Hudson was able to gear up for higher volume production, and built some 4,000 Invaders in just a year and a half.

The V12 Defenders acquitted themselves superbly in the Higgins PT boats; Higgins was the second largest builder of this class of high-speed craft after Elco, which used the Packard 2500 V12. Hall-Scott went all-out on Defender production, building over 5,000 of them during the war.

At the close of the war, ACF split into two entities, with H-S now conjoined with Brill, the bus and trolley maker. Not long after, Brill-H-S were then bought by Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft, which was looking to diversify with the wartime profits. The short story is that Hall-Scott continued to be bounced around, without any effective leadership. The diesel engine era was rapidly approaching, but H-S had no vision of how to thrive in the coming post war age.

Model 400: Superpower for Trucks

The Invader’s inherent qualities were too good to stay on the water, so a truck and bus version, the Model 400 was derived from it. This actually happened back in 1940, just before the war, but since most of its long life was after the war, it’s going to get its many accolades here.

Hall-Scott correctly saw that highway (and off-highway) trucks and their loads were getting bigger and longer, especially in the West, where maximum loading and length regulations were more generous than in the East. So it decided that the time for a more powerful engine had arrived. The massive 400 displaced 1091 cubic inches, and quickly established itself as the king of the road.

Here’s a dyno chart that backs up its reputation: 310 hp (on LPG fuel) at 2000 rpm, and a mighty 965 ft.lb. of torque. The gasoline version had a somehow lower compression ratio and made a mere 275 hp.

It’s important to know that the naturally-aspirated diesel engines of the time typically made 150-195 hp, and had significantly lower torque than the 400, due to the fact that diesels intrinsically make less torque than a comparable gas engine (without forced induction). The majority of gas engines at the time fell into that horsepower range too. The big Hall-Scott was in a whole different league.

The 400’s significantly higher output than the diesels of the time was attractive to operators where massive power was necessary, or where maintaining schedules on routes with extensive grades could offset its higher fuel consumption. The 400 had to earn its keep by increasing the utilization rate of the expensive equipment, and it did that for many operators, primarily in the western half of the country with its many mountains, long grades, giant logs and great distances. It was all in a day’s work for the 400.

A cross-section of the 400 shows the typical H-S features, including the separate cylinder block bolted to the crankcase and the ohc hemi head with twin spark plugs.

Although H-S had not had much of a presence in the OEM sector, with the arrival of the 400 a number of firms, including Autocar, International, Kenworth, Mack and Peterbilt added the 400 to their list of available engines. There were a number of derivatives over the years, and some 6,500 were built by 1958.

Time does equal money in the trucking business, and that was what kept the 400 selling in the face of ever-more popular diesel engines. But Hall-Scott saw the writing on the wall, and rightly decided they needed a diesel too, if they were to have a long-term future. If only they had done it rightly.

The Hall-Scott Diesel – Its Deadly Sin

Hall-Scott’s parent company, ACF, which was expanding its transit bus portfolio, saw the obvious need to have a diesel engine. Brill (also owned by ACF) sent its VP of Engineering to Europe to make a survey of all the diesel makers and develop recommendations for its own diesel. Other American engine makers (Buda, Waukesha, Hercules) were already working with European firms which had extensive experience with diesels.

But for one reason or another, ACF did not go that route, and simply tasked Hall-Scott to build a diesel engine (This was well after E.J.Hall had left the company). Overly eager to get into the diesel market, H-S’s management signed a contract to deliver ten diesel engines to a coach operator in Los Angeles…within 60days! This was a colossal and fatal mistake, totally underestimating what it took to design and build a proper diesel engine, whose compression ratio was four times that of the gas engines of the time. And that’s just one aspect.

The H-S engineers did the obvious: they “dieselized” their existing Model 175 bus engine, with highly predictable results, very much like GM did with their 5.7 L V8 diesel decades later. Many compromises had to be made. The ten engines essentially became rolling test beds, and the test was a bust: Broken crankshafts, burned pistons, and other failures required the engines to be pulled from service in short order. This was the first black eye that Hall-Scott ever endured, and it was totally their own doing, for lack of appreciation of the challenges involved.

H-S yanked the diesel from their bus and truck catalog, but continued to try to make it work as a marine engine, where the lower operating speeds were a hoped-for reprieve. The “Chieftain” diesel was advertised for a couple of years, but never gained any traction,as it was too heavy, too low on power and never truly reliable.

One can only speculate how Hall-Scott’s future would have been different had E.J.Hall still been there and had the time to design and develop a proper diesel engine.

But H-S was not yet ready to throw in the diesel towel. Take 2 involved a cooperation with Hercules and engineers from the Lanova Corp., a German firm whose diesel combustion chamber was commonly licensed at the time. The resulting engine, the Model 125, had no basis on any existing H-S engines, and looked quite unlike them. It was a relatively modest sized engine, and initial tests were promising, showing excellent economy. But in 1937, H-S received a massive order for V12 Defenders from the U.S.Navy, and there just weren’t enough resources to pursue both. So the 125 was still-born and was not revived after the war, as it was considered too small for the ever-larger trucks of the post-war era.

The Challenging Post War Years

The immediate post-war years were difficult ones for Hall-Scott, as the bus crashed after a brief surge, and the truck engine market was increasingly moving to diesels in the large trucks. The company had no real vision for where it should go, so it reverted to just cranking out more of the same, as it had since WW1. This strategy worked as long as there was still some demand for its high-power gas engines, but that was inherently a slowly dying market.

For what it’s worth, H-S was also shuffled around in various corporate reorganizations, spin-offs and sales. In the immediate post war era, H-S was lumped with Brill, and then that entity was bought by Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft Corp, which was a division of AVCO, and looking to diversify. Since AVCO also owned Continental Motors, they now had two engine makers, but Continental increasingly focused on aviation engines, a market H-S had abandoned.

AVCO’s plan was to use its experience in WW2 building planes in mass production to substantially increase bus production at Brill, which then had some 12% of the market. Since Hall-Scott’s production facilities in Berkeley were always rather modest-sized, the plan was that Continental’s Pennsylvania plant would expand and build H-S engines to power all those Brill buses.

All of this turned out badly. Continental’s engineers in Pennsylvania made changes to the long-proven H-S Model 136 horizontal bus engine that created issues. And the mass production of Brill buses in Nashville never got off the ground. The reality was that the post war years featured an exodus to the suburbs, and the subsequent decline in surface mass transportation, which were mostly still private companies dependent on fares. GM’s diesel transit buses were significantly more economical, and the quickly came to utterly dominate the market. In 1948, the whole venture collapsed. And in 1951, AVCO sold Brill (including H-S) to Allen & Co., an early private equity buyout firm.

Brill was the weaker of the two, and what meager profits H-S generated were used to underwrite Brill’s losses.

Hall-Scott did what so many other weak manufacturing companies in the 1950’s did: it pursued military contracts and used its expertise in making a variety products, such as power generators, gears, transmissions for helicopters, machine gun mechanisms, and others, including some Defender marine engines. They even opened a small second plant in Richmond to produce munitions. The Korean War and the Cold War boosted all of this defense spending, and it was a boon to so many smaller manufacturers.

ACF-Brill (H-S) was increasingly dependent on these contracts to survive, as it watched its civilian business languish. By 1954, Brill manufacturing was drastically cut back. H-S’s profits dwindled during these years, which meant there was no capital to invest in any new civilian product lines.

The H-S marine product line was pared down to just the Invader and Defender. The bus and truck line included a number of six cylinder engines in both vertical and horizontal formats. The Defender V12 was also offered in a stationary version. But there were no diesels and no four cylinders. The power range was from 130 hp to 900 hp.

H-S did “experiment” with a truck version of the big Defender V12. I assumed that these were essentially the same as the 2181 cubic inch Defender, making some 600 hp. I’ve come across one internet forum comment that this engine had a reduced capacity and actually was rated at 450 hp. That sounds credible; if H-S was going to pursue a market for an engine above the 300 hp 400; stepping up to 450 hp makes more sense than doubling it to 600 hp.

Since that truck-specific V12 was never put into production, we may never know for certain if this 1951 Kenworth had the 600 hp Defender or a prototype of the 450 hp engine. Other references to this truck refer to its “600 hp”, so I’m going to assume it’s the former.

As mentioned earlier, trucking in the 1950s expanded greatly, with many western states increasing maximum weights of 70,000 lbs and 45′ trailers, as well as other longer combinations. The advantages of faster operating speeds to maximize equipment utilization gave H-S something of a reprieve with its high-power gas engines, it wasn’t just diesel engines that were a growing threat to its business.

Other competitors in the gas engine market were introducing new high-output but compact and lighter V8s, such as those by Continental, Le Roi and Reo. The 400 was a physically large, long and heavy engine and did not readily fit into the shorter hoods of the trucks favored in the eastern half of the country. This is why “West Coast” trucks almost invariably had longer hoods, for the larger engines that often were used in them, including the H-S 400.

H-S did experiment with both supercharging, turbocharging and fuel injection, but none of these technologies found themselves except for a small batch of Model 442 that had a turbo and fuel injection and was sold to the military for large snow removal equipment.

The more serious issue was of course the growing popularity of diesels, whose market share increased steadily during the fifties and sixties. But it wasn’t just any diesels that were winning the sales wars; the pre-war Lanova and other pre-combustion chamber diesels were less efficient than the new direct injection diesels pioneered by Cummins (four stroke) and GM (two stroke). This is why the Lanova diesel that H-S had developed with Hercules was never developed after the war. The diesel market increasingly was dominated by GMC, Cummins and Caterpillar, due to their relentless investments in their technology and production efficiency. The smaller diesel manufacturers eventually fell away.

In addition to updated versions of the 400, the Models 855, 935 and 1091 (corresponding to their displacement), H-S finally broke the overhead-cam, hemi-head, unit-construction mold with a totally new smaller inline six in 1954, the Model 590. It was designed to be cheaper, lighter and operate at higher engine speeds. It had a “square” 5″ bore and stroke ratio, was a conventional design with a single casting for the block and crankcase, and—heresy—had pushrod actuated overhead valves and a conventional wedge-shaped combustion chamber. It replaced the older smaller engines in H-S’s line, which dated back to the late 20s or early ’30s. Its smaller physical size made it suitable for installation in a wider range of trucks and other vehicles. Its modern, simplified construction made it cheaper to build and sell.

Hopes were high for the 590, but it never met them. The market was just not interested. And that segment of the market was becoming even more crowded, as the Big 3 were now building high-power V8s in this power range. Since their engines were based on passenger car engines, they had a huge advantage in scale and cost, one that H-S couldn’t begin to overcome. In the 1950s, H-S was building only several hundred engines a year, a pittance compared to the mass producers.

These V8’s ran at much higher speeds than Hall-Scotts, up to twice as high. Thus they were able to generate significantly more hp per cubic inch and per pound, but it also meant that the torque was not nearly as high in relation to max. hp, and the torque peak was at a higher speed too. The Hall-Scott big sixes’ only advantage was to belt out enormous amount of torque at low operating speed, which still appealed to a small and shrinking group of buyers. One of the most loyal was the fire engine market.

Fire departments weren’t concerned about economy or efficiency; what they wanted—most of all in their pumpers—was raw power; the more the better. And the big Hall-Scotts delivered that. Another benefit was no oily smell or black smoke in the firehouses. For decades, many West Coast fire departments were often exclusively H-S powered for decades, such as in Los Angeles.And they often stayed in service well into the 1970s.

As a matter of fact, our nearby fire station in Los Gatos had a back-up pumper with a H-S in the late ’80s, and it was still used on occasion. I can still hear its wonderful exhaust as it accelerated down the street. It was very similar to this 1951 Kenworth pumper I recently found in Southern Oregon, but had an open cab.

Here’s a shot of its model 470 engine, which has a 5.5″ bore and 6″ stroke, resulting in 855 cubic inches (14 liters). Horsepower ratings for the 470 were between 250-300 hp.

Independent Again

Due to the difficulties that ACF-Brill experienced with its bus and trolley business, in 1954, it split up again, and Hall-Scott Motors was now independent again. That was hardly a good sign, as both companies went their own ways in an effort to survive.

The engine business was clearly moribund in the long run, so the directors decided to diversify, utilizing the company’s experience and capabilities in fields where there was seemingly more of a future. Like computers.

Yes, H-S purchased several small firms involved in the growing electronics field, and lumped them together in the new Electronics Division. There was also a Precision Sheet Metal Products Division, an Industrial Products Division as well as the now-called Power Division, featuring the aging line of engines.

Unfortunately there was no way to infuse some new thinking and technology from the electronics division to the engines, so the latter continued to stagnate. The 1955 H-S Annual report made mention of a new diesel engine and a turbocharged V-12 for trucks. The former should have happened but never did; the latter, an intriguing notion, didn’t either but then who was going to buy 900 or 1000 hp gas V-12s in the late fifties?

It was this same year that founder E.J.Hall passed away. After the ill-fated De Vaux-Hall, he went to France and helped Citroen with the development of its very advanced FWD Traction Avant cars. He returned to the US in 1935 and worked in a variety of companies. He did visit H-S in 1945, but his vision and engineering acumen were long missed.

A business consulting firm was hired to examine Hall-Scott’s engine operations and determined that it needed to sell between 80-120 engines a month to be profitable, but actual sales ran only about half that, and there were no prospects to improve that. The losses in the engine building were at least offset by healthy profits in selling parts to the fleet of existing Hall-Scott users.

That’s not to say drivers, mechanics and operators didn’t love their Hall-Scotts; quite the opposite. Drivers loved their bountuous torque, although the immense heat generated by burning all that fuel could make the cabs blistering hot in the summer, to the point of practically burning the driver’s feet. They could outrun any other engines on the grades, and for those drivers being paid by the mile (and not paying the fuel bill), it was money in the bank.

Mechanics preferred working on the compared to the dirty and diesels, and access to parts and disassembly of the heads and cylinder block was easily done with the engine still mounted in the truck.

Some operators, mostly smaller ones who placed a premium minimizing time over runs were willing to stomach their prodigious 1-3 mpg thirst.

So in terms of durability and reliability, there was no price to pay, except perhaps in their higher initial purchase price.

This rather remarkable documentation of the detailed costs of one truck that rolled over a million miles shows that the original engine never required a full overhaul; just the replacement of high-wear components. Their design, as well as the quality of the materials and workmanship made it a pleasure to work on them. Of course a million miles today is not that big a deal, but back than it was a considerable achievement. As an example, Greyhound Bus Lines used to rebuild their Detroit Diesel engines at between 450-650k miles.

But when it came to making purchasing decisions, very few fleet superintendents could justify their higher cost and thirst. The economics just didn’t pan out, despite how much they were loved by drivers and mechanics. Not only did a diesel get almost twice the mileage, diesel fuel was significantly cheaper too back then. Very few H-S powered trucks were being replaced with another one.

Hercules Motors Buys Hall Scott – The Finale

Hall-Scott’s finances deteriorated year-by-year. In 1957, H-S president Nelson told his board that the best option was to liquidate the company; more specifically, to prep H-S for a sale, so that the stock holders would see some return on their ownership. By cutting costs and other measures, H-S managed to squeeze out a profit in 1957 and 1958, and attract a buyer: Hercules Motors, another builder of engines.

The plan was to move H-S engine building to Hercules’ plant in Canton, OH., continue building them as long they there was a market for them, but focus on the profitable sales of parts. Some 13,000 H-S engines were still in service, and that was the main appeal to Hercules.And the large H-S engines actually complemented Hercules’ line, so that was deemed a good fit too, so now they could offer engines from 5 to 600 hp. Hercules also assumed it could build the H-S engines more economically.

Hercules paid $1.8 million for the inventory, tools and and parts, leaving the H-S plant in Berkeley still in the ownership of H-S stockholders. The plant was gutted in 1958, and parts of the plant and land would be sold off piecemeal over the coming years. And even the Electronics Division was sold off, as it too turned out to be less profitable than expected. The only question remaining was what to do with the pot of cash H-S now sat on.

The solution was to purchase 50% of the DuBois Holding Company, which manufactured and distributed industrial soaps and detergents. DuBois was very successful at that, with a 27-year string of unbroken chain of growth and profits. In 1960, H-S and DuBois fully merged, and Hall-Scott as an entity ceased to exist. But the H-S stockholders made out well; DuBois is still in existence, although its ownership has changed over the decades.

Hercules continued to offer the H-S line, consisting of the “smaller” 590 and the large engines. There was a modest improvement effort, which resulted in increased power, led by a turbocharged version of the large six with up to 450 hp.

But the end of the line was in sight: by 1970, even long-time loyal H-S user Crown bus no longer offered them, and in coming years would offer a factory kit to convert the large fleet of H-S powered Crown school buses to Cummins diesel power.

What hastened the end was White buying Hercules in 1966. White had been gobbling up competitors for years, and was now the largest HD truck builder. It had specific expectations in terms of what engines could meet its power-to-weight standards, and the big H-S sixes, which dated back to 1937, were not going to meet them. By the time the last Hall-Scott engine was built in 1970 by Hercules, it was simply out of date and not in tune with the times. The days of large spark-ignition truck engines was truly over. But the legend of the Hall-Scott engine endures, to this day.

Note: this primary source of this article is the book “Hall-Scott: The Untold Story of a Great American Engine Maker”, by Francis H. Bradford and Ric. A Dias. SAE Press. It’s the only in-depth book on the subject, and very recommendable.

Related reading/viewing:

Vintage Truck: 1951 Kenworth With 600 HP 2181 Cubic Inch Hall-Scott V12 – The World’s Most Powerful Factory Road Truck Of Its Time

Curbside Classic: 1951 Kenworth Fire Engine Pumper With Hall-Scott Engine – It Gets My Heart Pumping

Vintage Films: “Hall-Scott Power” (Parts 1-4) and “Success Story–Hall Scott”

Bus Stop Classic: ACF-Brill IC 41 – Silver Screen Standout

If you want to see the guts of a H-S aviation engine that’s been transplanted into a 1913 Peugeot racer, these two videos document its rebuilding. Part 1. Part 2.

Been waiting for this one – and it didn’t disappoint – great article…

Great read Paul, thank you. I’ve worked on exactly 2 Hall-Scotts in my life, one in a Crown Coach that was one of two commisioned by the Los Angeles County fire department for hauling crews and trainees around. 500 incher with a single carb but it was a real treat to drive. The other was a dual carb 855 twin ignition that repowered a 1929 American LaFrance triple combination pumper also an ex LA County unit. The cast iron Zenith carbs were huge, I could almost get my fist down the throat of them. Straight exhaust too, it didn’t bark but had a thud at idle changing to a serious rumble at speed. Beautiful engines. If you are ever near Bellflower, CA. stop by the Los Angeles County fire museum, they have several Hall Scotts in the collection including a cutaway.

And you can also see Squad 51 there too.

I’d say “CC’s Best Of 2023” has already been published on January 2…

Thanks for this excellent read, well worth waiting for. I’ve heard of -or better- read about the Hall-Scott gasoline truck engines of yore, the name popped up in all Dutch and American books I’ve been collecting since the late eighties/early nineties. But other than that the benzine/gasoline engines were very powerful, not much other helpful information. Thus, H-S remained a mysterious name and manufacturer. So that’s another mystery solved!

This was a fantastic read! I had known a little about Hall-Scott engines over the years, but not much. This piece gave me a real appreciation for these beasts.

I wondered if the lovely sounds of the PT-73 on the 60’s television show McHale’s Navy were made by Hall-Scotts, but it appears not. The boat used for cruising scenes was formerly the PT-694, a Vosper design powered by three Packard V-12s. However, the actual Historic PT-73 was a Higgins-built boat, so it should have had the Hall-Scotts when its crew scuttled it after it ran aground.

Wow, great discussion of a topic I knew little about. The stories of smaller manufacturers in the 1950s are often similar; a few months ago, I read James Ward’s book on the fall of Packard. They depended too much on military contracts, and the cycle of not having enough money to update your product, which leads to fewer sales, which leads to less money, continued until the end. Like you said, it would have been interesting to see how the company would have made out if Hall had stuck around to help the transition into diesel engines. He certainly seems like one of the unsung heroes of mechanical engineering.

The question of whether H-S would have survived with a proper diesel engine has been debated by H-S aficionados for decades. I’d vote “No”, for two reasons:

1) the truck/bus diesel market was being very aggressively pursued primarily by GM and Cummins (and later Caterpillar). GM was of course a behemoth, and Cummins was 100% diesel from day one, and very determined to succeed. Meanwhile, numerous smaller companies also had diesels but they all failed eventually, lacking the scale and resources.

2.) H-S had a unique selling proposition with their big gas engines: they were simply more powerful, and as such they really didn’t have any direct competition at that strata of the market. But that was never going to be the case with diesels, unless H-S could have jumped right in early on with exceptionally high-power forced-induction diesels. But Cummins already offered a supercharged diesel in the early ’50s, and soon offered turbocharging.

Undoubtedly H-S would have prolonged their life with a successful diesel engine, but it’s rather unlikely it would have allowed them to prosper in the long haul against these much larger competitors.

Curtiss Wright had the most efficient gasoline piston aircraft engines (Super Constellation and DC-7) and was fat with military and airline contracts, then the market shifted to jets and CW was left behind. Pratt and Whitney successfully made the transition, even with GE ahead of them.

What a way to kickstart the year! Amazing post full of historical and technical gems, plus some great illustrations (that Fageol, for instance), 95% new to me. Looks like they managed to end things gracefully, too – never a given.

I’d be interested to know more about E.J. Hall’s involvement with Citroën in the early 30s. I read about that period quite a bit, but I don’t recall seeing that name in French sources.

Thank you for this literary monument to H-S and for the education. Best of CC 2023 indeed, as was remarked above.

Hall’s involvement with Citroen was new to me; I’d forgotten about it when I read that book the first time. But that’s all that was said; no details. It might be difficult to find any more on that. Just what all he did after the time he left H-S has not been well documented; there’s no biography of him as far as I can tell.

You’ve mentioned writing up Hall-Scott a few times, and I can see why it took so long. You’ve outdone yourself, Paul – this is a thorough history. As a Berkeley native I never even heard of Hall-Scott until I started working for Peterbilt after college and learned about Bay Area automotive history from colleagues. I had never heard of Fageol either, or even knew that Peterbilt had started in my birth city of Oakland. Why don’t they teach kids in school about local industrial history, anyway?

The only tidbit I’d add is that the Hudson connection apparently brought the British engineer Reid Railton, famous for his work on speed record cars and boats, as well as the Railton Terraplane, to Berkeley to work for H-S. He lived out his life and died there in 1977.

https://berkeleyplaques.org/e-plaque/reid-railton/

Thanks for the additional info about Railton. I did not know about that.

Great Job Paul! Excellent as usual. I had no idea they were from the San Jose area.

What a treat to wake up to one of your masterpieces, Paul. Maybe an article on Hercules engines would be in order.

Thank you for your great effort to write a long, detailed article.

Wow, I would have never expected a 600 hp OHC hemi V-12 from 1951.

I’m impressed!

Great article, thanks! Many interesting facts I was not aware of.

Read that book about H-S myself a few years ago. You did a good job of covering it. There were a couple tidbits about the rivalry between Packard and H-S wrt the Liberty. After the war, Packard tried to claim the engine as entirely it’s own work, and Hall snorted that he had personally built more aircraft engines than Jessie Vincent had ever seen. Prior to WWI, H-S was the second largest aircraft engine maker in the US, only trailing Curtiss. If you look at the aircraft engines Vincent had tinkered with before the war, they look nothing like a Liberty. One the other hand, the Liberty looks very much like two H-S sixes on a common crank.

I am also struck by the common thread between H-S, Studebaker, and Curtiss-Wright. Each an early major player in it’s field. Each losing first mover advantage due to lack of investment. I wonder how much money ACF siphoned off of H-S. We know how the bankers that Fred Fish helped get their hooks into Studebaker drained out capital, including all the war profits. Same thing happened at Curtiss-Wright. In C-W’s case, it was Paul Shields, of Shields and Company that demanded all the war profits be paid out in dividends, instead of investing in developing jet engines. Like H-S and it’s failure to transition to diesels, C-W sat and watched it’s dominate position in airliner power die out, as airlines moved to jets.

If any engine ever justified a see-thru cover it would be a Hall-Scott. Pick your favorite year and model as they are all engineering works of art. For me it’s the Invader model 400. It looks like a high-end custom spec engine that was built today.

Thank you Paul for a nice article. There are small bits of the Hall-Scott company still left along Heinz street, though the main office is long gone. The majority of the MacCauley foundry buildings still exist one street over on Carleton, though they have been turned over to other uses, mostly artist lofts. The Ruckstell axle was sold to what became the Eaton Corporation and was an important part of it’s eventual leadership in the truck axle business.

Interesting that Packard and H-S both failed at about the same time, for somewhat similar reasons, ultimately coming down to ineffective leadership.

Typo, I should have said “Fantastic Article”

Wonderful, informative treatise on HS. Thank you, Paul!

What a great read!

The Hall-Scott story embodies the principles of innovation and the tenacity to constantly improve. A true success story that would benefit upcoming engineers when/if they need motivation.

Cheers

Great read Paul, Hall Scott built really incredible engines for a very long time, 600hp in 51 would have been amazing in a truck, modern day freight hauling performance so long ago.

Thank you, a very interesting article!

IHMO, the best article I’ve read in a long time, and the best here. A great start to 2023.

There is a thread on the Big Mack Trucks website about a pair of B-21 fire trucks that were pulled out of the woods. These rare trucks (only 9 built) have the Hall-Scott 1091 engine. So far one is running, the other nearly so.

https://www.bigmacktrucks.com/topic/70785-b-21-fire-truck/

Way late to the party here, as I just finished reading this fine piece (over a few days).

A best of 2023 candidate for sure as others have said above.

You outdid yourself here Paul. Kudos. I learned a lot from reading this one.

This seems like a good place to expand upon Hall-Scott’s efforts in the railroad market.

Hall-Scott supplied four engines to the Henry Ford-controlled Detroit Toledo & Ironton in 1926. They were installed in two gas-electric cars built by Pullman, one with a pair of opposite-rotation 5×6″ 6-cylinder engines (car # 36) and the other with a 5×7″ pair (car #35). These were installed vertically, not horizontally. Both cars used Westinghouse electrical gear, and were rated at 150hp @ 1700-1750 rpm.

I believe these power plants were similar if not identical to those used in the AC&F gas-electric buses of the time.

Photos of the engines:

https://www.lakestatesarchive.org/John-S-Ingles-Collection/DTI-Company-Files/i-9qD4XnQ

https://www.lakestatesarchive.org/John-S-Ingles-Collection/DTI-Company-Files/i-9kknrBZ

https://www.lakestatesarchive.org/John-S-Ingles-Collection/DTI-Company-Files/i-vkkC7Wd

https://www.lakestatesarchive.org/John-S-Ingles-Collection/DTI-Company-Files/i-czrBhzT

Hall-Scott’s entry into the full size railroad market was limited. The market for gas-electric cars beginning in the mid-1920s was dominated by Electro-Motive Corporation, who used Winton Engine Co. as its engine supplier; and J.G. Brill, who used a Westinghouse-built 250hp engine. Hall-Scott and Brill’s entry into the ACF Motors umbrella gave H-S access to Brill cars, and H-S gradually supplanted the Westinghouse design in 1927-9, primarily in twin-engine installations, but this amounted to somewhere around 40 cars. Brill and Westinghouse developed a high-horsepower engine in 6 or 8 cylinders (400hp and 535hp), and this engine in turn supplanted the H-S engine.

Hall-Scott’s engine for large railroad applications was initially rated at 275hp in 1927, and it appears to have redesigned around 1929 and increased to 300-350 hp @ 1100 rpm. The 1929 version was a 6-cylinder with 7.5″ bore and 9″ stroke (2,385.6 cubic inches). I believe the redesign was carried out to facilitate the use of distillate fuel.

“Distillate” was a catch-all term for a variety of petroleum fuels that were heavier than kerosene and lighter than diesel. A number of railroads bought or reworked cars in the mid-late 1920s to use this fuel, which was considerably less expensive than gasoline. This required modified carburetors, multiple spark plugs per cylinder, and high-energy ignitions systems. Even at that, distillate engines ran roughly, horsepower was reduced, maintenance was increased, and lube oil dilution was an issue. Suitably lightweight diesel engines would soon overtake this market, but not until the early 1930s. Union Pacific’s M-10000 was the last distillate installation, a Winton 191A, in February 1934. CB&Q’s first Zephyr, with a Winton 201A diesel, came in April 1934.

Hall-Scott would have one more fling with railroad cars. Brill built four “railbus” cars for the Norfolk Southern Railroad, two each in in 1933 and 1934. These used a Hall-Scott Model 180 6-cylinder horizontal underfloor engine, and a 3-speed mechanical transmission. ACF built three similar cars for Seaboard Air Line in 1935.

Thanks for republishing this informative article.