In part one of this series, the history and design fundamentals of Ford’s 335-series engines were examined. This article will delve into the details of numerous engine iterations of the Ford 335-series. Only being offered from 1970-82 in the North American market, Ford created a wide variety 335-series engines despite its short life span. The 351C had the most variations, which ranged from family car engines to one of the hottest engines of the muscle car era.

Ford enthusiasts typically identify engines by their VIN code, rather than the option code like on GM cars. So, as we examine each of the 335-series engine iterations, they will be identified by their configuration and engine code.

The 351C-2V: H-code

The 335-series engines were designed with high performance aspirations and racing potential in mind, but the fact was that the vast majority of the engines being built would be very conventional and installed in regular cars that had little to no performance ideations. This is where the 351C-2V comes into the picture. This engine was the low performance everyday 351C and was the most commonly produced version. The 351-2V used the open chamber heads with the small “2V” sized ports and a mild short duration, low lift camshaft. It was rated at 250 hp and 355-ft lbs (gross) for 1970, had 9.5:1 to compression and could run on regular fuel.

Due to the ever tightening emissions standards, Ford made annual changes to help ensure the engine would burn cleaner. For 1971, 1972 and 1973 year the compression fell to 9.0:1, 8.6:1 and 8.0:1 where it stayed until the engine went out of production in 1974. This was done with an increase to the combustion chamber size in 1971 and in subsequent years by increasing the piston dish volume. To further aid cleaner emissions, Ford retarded the camshaft timing by 4 degrees and added an EGR system in the 1973 model year. The retarded camshaft timing significantly hurt performance and engine response, as this change effectively lowers the dynamic compression ratio. These changes caused reductions to the horsepower ratings; in its final year it was rated at 162 hp (SAE net).

It should be noted that Ford used the “H-code” interchangeably between the 351W-2V and the 351C-2V. Ordering a 351-2V engine meant that you could get either version but both the 351C-2V and 351W-2V H-Code engines had basically identical power outputs. The H-code 351C-2V was mostly used intermediate and pony car Ford and Mercurys but some full-size cars got them too.

The 351-4V: M Code

When Ford began to advertise the “new” 351-4V for 1970, this was the engine it was writing about. While the H-code 351-2V was pretty vanilla, this engine was designed to appeal to the performance enthusiast. The M-Code 351C had an Autolite 4300-A 630 CFM carburetor, large port 4V cylinder heads with small “quench” combustion chambers, 2.19”/1.71” valves and flat top pistons. The advertised compression ratio was 11.0:1, although this was somewhat inflated (the measured compression ratio was actually 9.95:1). Nevertheless, premium fuel was mandatory. Because of the excellent breathing abilities and the high compression ratio, this engine used a relatively mild camshaft with 268/280 degrees of duration and 0.427/0.453” of lift, and still was able to produce 300 hp and 380 ft-lbs of torque (gross).

This engine was only available in the FoMoCo’s more sporty cars, which meant the Torinos, Montegos, Mustang and Cougar. For 1971, to reduce emissions, Ford dropped the compression ratio by increasing the combustion chamber size. This resulted in the advertised compression ratio dropping to 10.7:1 (measured compression ratio 9.59:1). There were no further revisions to the engine, and the horsepower rating dropped to 285hp and 370 ft-lbs (gross). The M-code went out of production after 1971.

A 1970 Ford Mustang with a 351C-4V M-Code engine. The M-code was also available with ram air through a shaker hood.

The M-Code 351-4V was decent performer. In Motor Trend’s Car of the Year test, a 1970 Torino quipped with a 351-4V consistently out accelerated a more powerful 360-hp 429 Torino. Motor Trend said “Run-for-run the lighter 351 Torino is the quicker accelerating [car].” Car Life commented in its road test of a 1970 M-Code Torino that “this is the first really good mid-sized engine from Ford.”

351-4V Cobra-Jet: Q-Code

The closed chamber high compression heads used on the M-code 351-4V were not conducive to clean emissions. In the spring of the 1971 model year, Ford added the low compression cleaner burning 351 Cobra-Jet to the Ford Mustang line. For the 1972 model year the 351-CJ fully replaced the discontinued M-code 351C while all high performance variations of the 429 (for civilian cars) were discontinued. This meant the 351C-4V was Ford’s only high performance engine. Reducing the compression ratio of an engine dramatically lowers its performance. Nevertheless as the last performance engine, Ford engineers went all out to produce one of the best emissions friendly performance engines of the era.

The 351-CJ Q-code was introduced late in the 1971 model year in the Mustang. Initially it was sold alongside the M-code. For 1972 the M-code was phased out and completely replaced by the Q-code.

To ensure the engine would burn cleaner, the 351-CJ used open chamber 4V cylinder heads. The larger open combustion chamber decreased the compression to an advertised 9.0:1 (actual compression was 8.74:1), allowing it to burn regular fuel. These heads still used the same large 4V ports and valves that were also used by M-Code engine. To help compensate for the decrease in compression, Ford used a more aggressive camshaft. The camshaft duration was increased to 270/290 degrees and lift was increased to 0.481/0.490 inches. To compliment the new cam, cars equipped with this engine got a small diameter high stall torque converter. Ford engineers made other improvements over the M-Code, including a stronger 4-bolt main block, and a larger 750 CFM Autolite 4300-D carburetor. The end result was the engine being rated at 280 hp, only 5 hp less than the 1971 M-code.

For 1972 the 351-CJ production was in full swing, and it was used in the Mustang, Cougar, Torino and Montego. The engine only saw one minor revision from the 1971 version, being the camshaft timing retarded 4 degrees. With the introduction of the SAE net ratings for 1972, Ford went a little strange on rating their engines. Unlike the other manufactures, Ford had multiple ratings for identical engines. So, the 351CJ was now rated at 266 hp in Mustangs and Cougars and 248 hp in the intermediate cars, despite the fact they were identical. For 1972, both numbers were very good, especially for a mid-sized displacement engine. Nevertheless, even federally certified Q-code engines were saddled with emission control devices that hampered drivability and part throttle performance.

Most Q-code air cleaners had an auxiliary door which would open to allow more airflow at wide open throttle. Some were also available with Ram Air.

Facing ever tightening emissions standards, for the 1973 model year an EGR valve was added to the 351-CJ. The combustion chamber sized was increased further and the pistons used a small dish which decreased the compression to 8.0:1 advertised (8.12:1 measured). Although the 4V heads large port heads were used, the valve sizes were reduced to 2.04”/1.65”, the same as the 2V heads. Interestingly, these 4V heads with the smaller valves actually have excellent performance potential, since the small valves are less shrouded in the 4” bore. The end result was a minimal power rating difference from 1973, with the Mustang/Cougar engine still rated at 266 hp (SAE net) and the Torino/Montego engine rated at 246 hp (SAE net).

Although Q-codes had good performance for the times, drivability was affected by the rudimentary emissions controls. In 1972 the vacuum spark advance was limited due to the Electronic Spark-Control System, which limited the vacuum advance depending on temperature and speed.

1974 was the last year for the Q-Code engine. With the Mustang switching to the smaller Mustang II platform, the engine was now only offered Ford/Mercury intermediates. Ford was still inconsistent with its horsepower ratings and despite no changes from the 1974 engine, the Q-code rating was revised to 255 hp (SAE net).

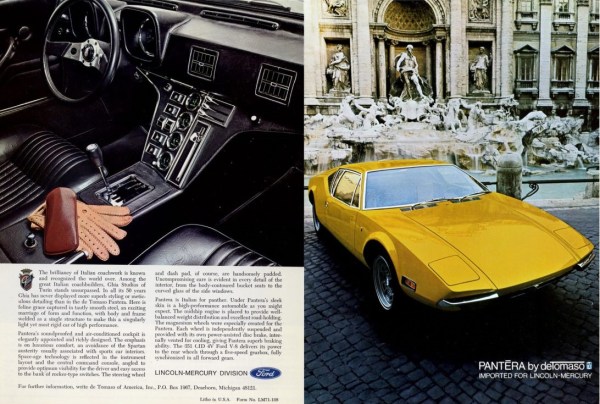

The Q-Code 351-CJ was a good performer for its day and had output as good as or better than other de-smogged competitors, such as Chevrolet’s LT-1 and L-82 and Chrysler’s 340. This version of the 351 also powered the many DeTomaso Panteras. Road Test magazine tested a 1972 Mercury Montego MX with a 351-CJ. They said “Despite a two point drop in compression ratio…[this engine] remains a potent performer.” However, Cars Magazine noted the decreased driveability in a road test of a 1972 Ford Gran Torino Sport with a 351CJ. They said “Throttle response isn’t what it used to be and you just have to accept the sloppier performance dictated by the use of smog controls.” Most 1972 cars with a 351-CJ ran the ¼ mile in the mid to high 15 second range, while later iterations were slightly slower.

Boss 351/351 HO: R-Code

The 1970 M-Code 351C was a relatively mildly tuned engine, even though it was rated at 300 hp. Ford unveiled the true potential of the 351C with the Boss 351 engine introduced partway through the 1971 model year. This engine was one of Ford’s most impressive performance engines of the era. The Boss 351 started with a 4-bolt main block, 4V quench chamber heads, forged domed pistons, and forged connecting rods that were shot-peened and magnafluxed with 180,000 PSI 3/8-inch nuts and bolts. Compression was advertised at 11.0:1 (10.63:1 measured), meaning premium fuel was required. All 335-series engines used high-nodular cast iron crankshafts, but Boss 351 cranks were specially selected to have more than 90% nodularity. The solid lifter camshaft had 290/290 degrees of duration and 0.477”/0.477” of lift. It used more durable single groove valves and stiffer valve springs. The solid lifters required adjustable valve train. Consequently, the R-code engines used adjustable rocker arms mounted on screw-in studs rather than the bolt down pedestal mounts of the hydraulic lifter engines. The R-Code engines were the only 335-series engines that used an adjustable valve train.

With the big free flowing ports and valves, this engine needed to breath, so it was equipped with a low restriction aluminum intake manifold and an Autolite 4300-D 750 CFM carburetor which was fed by a Ram Air induction. Rather than stamped steel valve covers, the Boss got finned cast aluminum valve covers. For 1971 the R-Code was only available in the Mustang, as the Boss 351. In total, there were only 1,806 Boss 351 Mustangs manufactured for the 1971 model year.

The R-Code Boss 351 was rated at 330hp (gross), only 5 hp less than the 428 CJ. We all know engines were over and underrated at this time, but based on the performance times that the Boss 351 ran in the larger, heavier 1971 Mustang, it probably wasn’t putting out much less power than a 428 CJ. Car and Driver was able to run the quarter mile in 14.1 seconds at 100.6 mph. With powershifting, the car hit 13.9 seconds at 102 mph. Car and Driver said “The engineers come off as the real heroes in the development of the Mustang Boss 351. It offers drag strip performance that most super cars with 100 cu. in more displacement will envy and generates high lateral cornering forces.” Motor Trend was also impressed with the Boss 351’s performance and were able to better the C/D times, running the quarter mile in 13.8 seconds at 104 mph.

The R-Code 351Cs used an adjustable valve train. The conventional rocker arm is on the left, and the adjustable on the right. Adjustable rockers used studs and guide plates, as shown on the cylinder head to the right.

The Mustang Boss 351 only lived for one year, but the R-Code 351 survived for one more year. Ford had to revise the R-Code for 1972 to pass the tighter emission standards. In doing so it lost a fair bit of power and performance. Ford renamed it the 351 HO and like the 1971 engine, it was only available in the Mustang. Ford struggled to get this engine emission certified and as a result it wasn’t available until the latter half of the 1972 model year. Only 398 engines were produced.

The 1972 351HO was a low compression emission friendly Boss 351 and was nearly identical in appearance.

To reduce the emissions, Ford lowered the compression to an advertised 9.2:1 (9.0:1 measured). This was accomplished by switching to open chamber combustion chambers and flattop pistons. The camshaft was revised to have less duration, 275/275 degrees, but compensated with slightly higher lift of 0.491”/0.491”. It continued to use the same carburetor and intake, but the carburetor was recalibrated for cleaner emissions. The only other change was that the Ram Air system was no longer used.

As a result, this cleaner R-Code engine performed well by 1972 standards, but the decrease in driveability and performance was noted. A 1972 Mustang R-Code was tested by Car and Driver. It ran the ¼ mile in 15.1 seconds at 95.6 mph. This was about 1 second slower and 5 mph slower than the 1971 Boss 351. Car and Driver said “This year they call it the 351 HO: last year it was the Boss. Ford hasn’t dropped the Boss part for nothing.” The Ford engineer on hand during the test talked “about potential rather than what the 351 does right out of the box. Emissions comes first these days, power second.”

After the 1972 model year, Ford dropped the R-Code 351C, leaving the Q-Code as its only performance engine.

The 351C was one of the most powerful engines during 1972-1974, and it made the most hp/ci of all American performance engines during this time.

400-2V: S- Code

The 400 was deigned similarly to the H-Code 351C, as a regular engine for everyday cars. As such, it was only produced as a regular fuel, mildly tuned, low-performance 2-barrel engine. There was never a production 400 4-barrel produced. 400s used a 2V open chamber head that was virtually identical to the 351-2V and a mild camshaft designed for low end torque.

For its 1971 model year introduction, the 400 was rated at 260 hp and 400 ft-lbs of torque (gross). The 400 only produced 20 more horsepower than the 1971 351-2V, but it produced a significant 50 lbs-ft more torque and at a lower RPM peak. Road Test magazine tested a 1971 Ford LTD Brougham with a 400-2V engine. They said the 400 is “pretty much a carbon copy of the advanced, light, tough 351, it produces 400 lbs-ft of torque at a rather low (for a V8) 2,200 RPM.” They went on to say that the “ the extra 20 horsepower the engine provides over the base 351 makes the car noticeably livelier” and that “The new 400 is smooth and responsive with an excellent low end toque curve… a really heavy footed driver starting from idle can fast wear down the right rear tire.”

Like the 351C, the 400 had to be quickly adapted to the ever tightening emissions standards, so minor changes occurred in 1972. Ford reduced the compression ratio slightly to 8.4:1 by using dished pistons. For 1973, the 400 had its compression reduced again, now at 8.0:1. Ford also now used a timing set that retarded the camshaft timing 6 degrees, effectively reducing the dynamic compression ratio further.

The Ford 400 was only ever produced in 2V (2-bbl) configurations. This is a Autolite 2100 from a 1972 400.

After the addition of electronic ignition in 1974, the 400 saw significant changes for the 1975 model year. The much more strict 1975 emissions requirements caused the cylinder heads to be redesigned. The new castings had more restrictive exhaust ports due to the redesigned cooling jackets and cast-in Thermactor passages. This along with the newly introduced restrictive catalytic converters resulted in the 1975 400 being the lowest performing variant.

From 1977-82, Ford trucks used the 351M and 400 engines. For 4×4 trucks like this 1979 model, the 400-2V was the largest most powerful engine option.

Ford continued to revise the 400 on a yearly basis. Horsepower increased the output from the 1975 low point of 158 hp to a high of 180 hp until it dropped back down again to 159 hp in 1979, the last year it was offered in passenger cars. However, further changes occurred in 1977 when Ford introduced the 400 into the truck line-up. Since the engine could be equipped with a manual transmission in trucks, Ford introduced an engine block with strengthened main bearing webs, making it one of the strongest factory engine block castings of all 335-series engines. These reinforced blocks were also phased into passenger cars once the old castings were used up. By the end of the 1979 model year the 400 was phased out of the car line-ups but it remained available until the 1982 model year in Ford trucks.

The 351M-2V: H-code

By the 1975 model year, Ford had no performance engines in its line-up. Concern shifted to producing engines that were clean burning and to lower production costs. Consequentially, the 351C ended production in 1974 and was replaced with the 351M. The whole purpose of the 351M was to reduce production costs. Rather than having two engine block sizes, the short deck 351C and tall deck 400, it was cheaper to destroke the tall deck 400 to produce a 351 ci engine. This maximized part interchangeability between the two engine displacements. The new 351 was given the “M” designation to distinguish it from the 351C and the 351W. Most agree the “M” was for modified, but some claim it was “Michigan” or “Midland.” Ford never said what it meant officially. Of note, the 400 Ford has no designation, despite the commonly misused 400M moniker. Why would Ford need an identifier when it only produced one 400?

Although similar in appearance to the 351C, the 351M used the larger 400 block. The red arrows show some block identifiers for the tall deck block. Note that not all 351M/400 blocks have the raised wall casting (right arrow), but no 351C engine has one.

Visually, the 351M looked very similar to the 351C and many can mistake the two at a glance. The 351M, however, was wider and taller like the 400 to which it was visually identical. It shared almost all of its components with the 400, with the only unique parts being the pistons and the crankshaft. Since the 351M used the same block as the 400, it also used the same motor mounts and the same larger bell housing pattern of the 400.

A 351M in a 1979 Ford Cougar. This was the last year the 351M was offered in cars, and it was the largest engine offering for the Cougar in 1979.

The 351M was a low-performance engine and was only equipped with 8:1 compression and a 2-barrel carburetor. Like the 351C-2V that preceded it, it was equipped with 2V heads that used the smaller ports and valves. However, it used the more restrictive cylinder head castings that the 1975 and newer 400 used. The 351M was also saddled with retarded camshaft timing, and the rudimentary emissions controls of the day that compromised driveability.

Just like the 351C-2V, the H-Code 351M was used interchangeably with the H-code 351W-2V. This meant that if you ordered a 351-2V engine, you could have randomly ended up with either version of the engine. The only exception to this rule was Ford’s compact Granada and Monarch and the 1979 Panther cars, which used the 351W exclusively and Ford trucks which used the 351M exclusively. Nevertheless, both engines were saddled with equally bad tuning as a band aid to help produced cleaner emission, and both were rated within a few horsepower of one another for each model year. Throughout its production, the 351M-2V engine typically produced approximately 150 hp (net), but some versions were even less.

Both the 351M and 400 Ford engine blocks developed a reputation for cracking, but the reality was it this was only a problem for some of these engines. The 400 engine blocks were cast at the Dearborn Iron Foundry and the Cleveland Foundry for 1971-1972 and had no issues. For 1973 and beyond, the blocks were cast at the Cleveland Foundry or the Michigan Casting Center. Only engine blocks cast before March 2, 1977 at the Michigan Casting Center are prone to cracking. After that date, the Michigan Casting Center blocks were corrected.

The 351M was a compromised design. While it still possesses all of the advantages of the 335-series family, it was saddled with the worst heads and was produced during the darkest days in Detroit. Like the 400, the 351M was last installed in Ford passenger cars in 1979 and Ford trucks for the 1982 model year. While there is potential to build a 351M today to be a better performer, limited aftermarket support means there are no off-the-shelf high performance pistons options. In addition, the 351C has a lighter block, and less rotating mass for the same displacement. Today, many believe the best was to build a 351M is to replace the crankshaft with a Ford 400 crankshaft or an aftermarket stroker crankshaft.

Australian 351C and 302C

For the 1970 model year, Ford of Australia started to import 351C engine assemblies from Ford of USA to replace the formerly imported 351W. The 351Cs imported to Australia were the same two variants offered in the US market, the 351C-2V and a 351C-4V. Like the US, the majority of the engines sold were the low performance 351C-2V.

The first 351C produced at Geelong in the fall of 1971 is shown here with key Ford of Australia engineering staff.

In November 1971, Ford of Australia began to manufacture the 351C locally. The Geelong engine plant imported engine blocks cast in the USA, but the remaining engine parts were manufactured at the Australian plant. Geelong built both a 351C-2V and 351C-4V, but they were not the same as the US market engines. To save on tooling costs, Ford of Australia only cast one cylinder head, which was essentially the same as an American market 351-2V cylinder head. That meant all Geelong built 351Cs used large open chambers and the smaller 2V ports. Consequentially, Geelong also had to cast a unique 4-barrel intake manifold that was compatible with the small port heads.

The 1971 Falcon XY GT HO Phase III used an imported 351C-4V. The Aussies started with a M-Code 351C and increased performance with a larger carburetor, more aggressive camshaft and high performance exhaust. The 351C made among one of the fastest sedans in the world, with a claimed top speed of over 140 mph.

Geelong only had the tooling to produce the 351C engines, meaning the base 302 engines would still need to be imported from the USA. This would result in the 302 costing more than the locally produced 351C. So, Ford of Australia decided to produce its own 302 variant using the 351C as the basis. By destroking the 351C with a 3” stroke crankshaft, Geelong created the Australian market exclusive 302C. Similar to the 351M, the 302C’s design was compromised in order to minimize production costs.

All 351C heads cast at Geelong were open chamber, all 302C were closed, but both used the small 2V ports. All of the Aussie built engines had compression of about 9:1, higher than all American engines made after 1971.

The 302C and 351C shared the same engine block and pistons. However, to do so, the 302 required longer 6.020” connecting rods. This resulted in a less than ideal connecting rod-to-stroke ratio of 2.01:1. The 302C used a unique cylinder head design. The shorter stroke required a smaller combustion chamber to produce an acceptable compression ratio. To do so, the quench combustion chamber was utilized, which decreased the combustion chamber to a volume of 56.4–59.4 cc. This was the smallest combustion chamber of any 335-series engine cylinder head. Since this was a small displacement low-performance engine, the 302C head used the small 2V ports and valves. So, the 302C cylinder heads were the only cylinder heads with a quench combustion chambers and the small 2V ports.

This 1976 Falcon XC could be equipped with a 302C or a 351C, both of which were made at the Geelong plant.

Ford of Australia received news that Ford of USA was stopping production of the 351C in the US market after the 1974 model year. Geelong purchased the US tooling so that it could begin to cast its own cylinder blocks. To ensure there was no engine production stoppage, Ford of Australia ordered 60,000 engine blocks from Ford in the USA. By 1975 Geelong began casting engine blocks. Production of the 302C and the 351C continued until December 1981, but supplies lasted until the mid-1980s. These Australian Cleveland engines were not only used in Ford cars, but also were used in Australian market Ford F-Series trucks, making them the only Ford trucks to get 351Cs. The Australian built 351Cs were also used by DeTomaso after the supply of US made 351Cs was exhausted.

The 351C was used in NASCAR well past American production ended in 1974. In 1975, Geelong started supplying the racing 351C blocks. Bill Elliot’s T-Bird, shown here, had a Australian 351C block.

NASCAR continued to use the 351C well past 1974 and by 1975 the American made block supply was almost depleted. As a result, the Geelong Foundry began to cast new engine blocks for NASCAR. Like the American made NASCAR blocks, the Geelong NASCAR blocks were strengthened for racing. These Geelong made NASCAR blocks were used until the mid-1980s when it was replaced by a new American made Windsor based racing block. I wonder how many NASCAR fans had any idea that the Fords of that era were using “imported” engine blocks!

Geelong cast two runs of racing 351C blocks. This is one of the later “pillow blocks” cast in the early 1980s. The majority of the second batch of blocks were poorly cast, and rejected for racing use. Ford of Australia ended up installing the rejected racing blocks in production cars.

The Ford 335-series engine was a short lived engine family. While it never got to live to its full potential, today, these engines still are used and loved by a small and dedicated group of enthusiasts. I hope after reading these articles, the excellent design and engineering of this engine family can also be appreciated by fellow CCer’s.

Just wonderful stuff Vince, truly. What detail, and effort.

Rather incredible to me that the (Oz) Falcon GTHO 351’s, and the concomitant race-winners fitted with it never had the enormous ports of the 4V heads you showed last time (despite being advertised here as “4V’s”, surely implying those heads). Somehow, they still made something around 380bhp or more, and it’s clear they really must have done so, partly because of road tests, but also the race wins. Possibly also worth me saying the Oz V8’s never had 4-bolt mains available to produce such.

I knew (vaguely) that Ford Oz imported a bunch of blocks when US 335 production ceased, but 60K, just wow!

Lastly, that Oz 302 oddball was always a bit low-powered, certainly a bit thirsty, but also gloriously, Lexusly-smooth and quiet and long-lived, and I’d lay a safe bet it outsold the 351 in fuel-cost-conscious Oz by a lot.

Rather incredible to me that the (Oz) Falcon GTHO 351’s, and the concomitant race-winners fitted with it never had the enormous ports of the 4V heads you showed last time

Not so incredible, see in the previous article the table on the head’s flow. They are similar up to some lift, then the 4Vs take off. The locals also know how to set up an engine 😉

Well, yes yes, all very well, but that’s not much use for the non-huge-holed 2V’s at Bathurst, surely? 6,500 rpm & 160 mph down Conrod Straight & all that, what?

(Also, for gorsakes, don’t assume I have a clue what I’m talking about, ask Mr Vince here, who can not only explain it magnificently, but prove it too!)

Thanks for the comment Justy. As for the Aussie engines, keep in mind the earliest 351Cs in Australia are completely US imports, including the large 4V heads. The most powerful example used in the 1971 Falcon XY GT HO Phase III, used the US made large 4V heads. From what I could find, it basically was a US M-code 351C, but it had an upgraded cam, exhaust and bigger carb. This would have really woken up the mildly tuned M-code engine. The Phase III engine was only rated at 300 hp, but many “estimate” it made 360-380 hp. The reality is, estimates are worthless and mostly folklore IMO. From the performance numbers the Phase III ran, It probably put out a bit less power than a US made Boss 351, which was only rated at 330 hp gross (although probably underrrated).

Later versions of the Aussie engines all used the small port heads, but still performed well because they had higher compression than any of the US counterparts made after 1971. And, remember, that the 2V heads are still very capable heads, able to support 400 hp, Many people prefer them due to the strong low end power they can produce. As for the racing versions, I wouldn’t be surprised if most teams kept a stock pile of 4V heads.

No, thank you, Mr V, sir.

I’ll only add that, swimming well out of my depth – having not even attended basic lessons & therefore just a drowner, really – I would say that the power (say 360 hp) and weight (3400-odd lbs) DO likely add up to about what the fastest Oz XY Falcons could do, ish, and thus it’s maybe/maybe not folklore about outputs.

Also, I forget a fundamental difference past 1971(?), good old lead. We didn’t get round to banning the lovely stuff till 1986.

Maybe folklore was a poor choice of words. The problem with these power “estimates” is that they aren’t based on anything tangible or measurable. Gross horsepower ratings were dubious at best, then people estimate a gross rating?

What we can compare is the performance data, and a Phase III did not accelerate as well as the 330 hp Boss 351, being about 1/2 a second slower in the quarter mile. Of course there are other variables, like the Phase III used steeper gears, but it was a fair bit lighter than the Mustang. And of course the test data from that time isn’t always the most reliable, especially since I can’t find a primary source for the Phase III. Still, I’d be still willing to be the Boss 351 would come out ahead of the Phase III engine if both were put on dynos today.

I briefly owned a 1972 Torino (maybe it was Gran? Too brief to remember) station wagon winter beater powered by the 400-2V. The guy I bought it from was the son of the original owner, who claimed his dad bought it to tow the family camper trailer. Boy, it sure did have the torques! Everything around the powertrain was falling apart, but whaddaya want for $175 1982 dollars?

One question about the content, and as a novice, it affected my readability… (Maybe it’s just me??)

I’m not nearly enough of a carburetor geek to understand why some carbs have “barrels” and other carbs have “venturis”, but I recall that at least in that era, Ford used “2V” and “4V” to describe their carbs. And from the article I learned that each carb type had its own associated head, and that you’ve called the heads what Ford called them, based on carb choice. But from a modern perspective, the phrase “4V head” means “4 valves per cylinder”. So when I first encountered that terminology in this post, I thought to myself “Wait a minute! Did Ford build a 32-valve V-8 in 1970??”

I wonder if there’s a way to clarify that within the post.

“I’m not nearly enough of a carburetor geek to understand why some carbs have “barrels” and other carbs have “venturis”

No need to be a carb geek in the age of fuel injection, but the phrases are interchangeable- Venturi is the technical name for the internal passages, and barrel is a slang term sorta based on the outside appearance of the carburetor housing.

Ford did offer a “variable venturi” carburetor in the late seventies and early eighties, but it was still based around the existing technology. The carb added a movable plate that varied the carb’s throat size, but the venturi design and “barrel” count remained the same.

BTW, I’d argue VV technology wasn’t new, since SU carbs used a variable throat size going back 30+ years, but Ford’s design rotated the blocking plate 90 degrees and did not have a needle jet.

Evan, I tried to use the Ford terminology in the article, but it does make it somewhat confusing. While most manufactures used “barrels” to describe carburetors, Ford decided to use “Venturis” instead. As Dave says above, both are describing the same thing in the carburetor. So a 2V (venturi) carburetor is the same as a 2-bbl (barrel) carburetor. Each carburetor “barrel” actually have a venturi shape, so Ford’s description was more technically correct.

Now the confusing part is that Ford also called its heads 2V and 4V. Really they are just names applied to a small port and large port heads. So the 2V are small port heads and the 4V are large port heads. For Ford in the USA, the small port 2V heads only used 2V (2-bbl) carburetors, while the large port 4V heads only used 4V (4-bbl) carburetors. Ford of Australia broke this convention and used the 2V (small port) heads, with a 4V (4-bbl) carburetor.

Today, with a combination of factory and aftermarket parts, you can run almost any combination heads and or carburetors.I hope this explanation makes some more sense. Ford’s nomenclature wasn’t the most clear.

Being a Ford guy before I started driving we have always said, among ourselves, two barrel or four barrel. However, when I write what my engine is, or any one else, I write 302-2V and 302-4V. Among ourselves when one says they have a two barrel 302 we also know it has the open heads in 1968. If I say four barrel it means I have the closed heads on my 302 making it a high compression J code. Those heads seem to be hard to come by nowadays.

I don’t think J-Codes were big sellers when new, plus one year only.

The 302 was an economy oriented engine then, aimed at economy oriented buyers. Perhaps many of these people perhaps balked at the notion of extra fuel expense for premium. Just my theory.

As per the fuel economy I’m not sure that many people were paying attention or cared about that back in 1968. Remember there were gas wars and I, myself, recall paying 0.29 cents for premium in 1970. My father, who bought the car, also looked at the 4 cylinder Porsche 912 and Volvo 1800 plus a 6 cylinder Mercedes.

The Cougar was a display floor car and knowing my father didn’t know engines I believe he was completely unaware. He never mentioned or complained that the car got 13 mpg and in fact I didn’t either as a 16 year old. Today the engine gets 17-18 mpg under judicious acceleration due to modifications.

Yes someone did build 4v heads for the 351 family in the 80’s here in the states I think. ? CHK with hotrod magazine. In the states. I think I have the mag. That listed the ad about the 4v heads. I was shocked when I saw those heads listed in the mag. Hotrod mag. 80’s. Don’t know the yr or month of that article

I cannot get over the multiplicity of designs, all designated as 351s, and shuffled randomly with each other in production. What I find fascinating is how it made sense to manufacture different families of 351s rather than picking one design and running with it.

Which I guess they eventually did, after the 351W became the last man standing in truck production, running through 1996, IIRC. It is interesting how the oldest design of the bunch wound up being the survivor, but I guess its kinship with the 302/5.0 was what saved its bacon.

An excellent series, Vince. You have answered many, many questions about this interesting but little-understood engine family.

It’s all about production capacity and utilization. Obviously the Windsor facility got maxed out by the explosive growth of the Mustang. They could not meet the demand; there was a time in ’66 that the 289 could not really be had in full size Fords, and the FE 352 was installed to non-ordered cars.

Since the Cleveland facility was to focus on the 351 initially, it made sense to make changes to it, as it was going to be new tooling anyway.

But when V8 engines fell out of favor after the first energy crisis, the Cleveland engines’ fate was sealed.

But yeah, it’s a lot like the multiple V8s used in GM cars in the 80s.

Yup — whenever there’s a question to the effect of, “Why the hell did they/didn’t they … ?” there’s a good chance the answer is “production capacity.”

Well GM had 4 engines they called 350 that were entirely different other than 3 of them shared a bellhousing. They also had 3 engines that they called 455 even though one of them was another 454. They also had 3 400’s. To be fair I know at GM they handed down an edict on advertised displacements so they weren’t one upping other GM brands.

So Ford having 4 different 352s, even if they called 3 of them 351s doesn’t look as odd in that light.

A lot of it had to do with the growth of that mid 300 ci segment that they couldn’t keep up with on a single line. So since a new line and new tooling was going to be required, it made sense to produce an engine designed to fit that segment from the get go rather than the quickly modified small block. The quick drop of volume in that segment following the gas crisis, is also why it made sense for the new 351M that shared most of its parts with the 400.

While GM certainly had many variations of engines with the same (or similar) displacements, it does sort of make more sense for them since each division was fairly autonomous. They had a history of developing their own chassis and engines, even if bodies were shared. Of course, this was ending in the 1970s.

Ford though shared engines between it’s divisions. So it makes a little less sense to have multiple engine designs for the same displacements. Ford potentially could have had all 351s follow the 351C design in 1970, even those made in the Windsor plant. Chevrolet small blocks were produced at multiple factories and were all the same. However, with the 302 was being produced in Windsor as well, and they must have figured it was most cost effective to stick with the Windsor design. Knowing the history gives some insight to why Ford did what they did, even it it seems strange today.

Yes they could have stopped production on the 351W and had all 351s be the Cleveland design, but that would have been even more expensive as they would have another set of tools to buy, not to mention down time for the change over. Not to mention that the 351W tooling still had some amortizing to do.

This didn’t stop with the pushrod engines either. When it was time to up capacity of the modular for use in trucks they did not add a second line making the 2v 4.6 Romeo. Instead they made a number of changes and created the 4.6 Windsor.

I always figured the biggest black mark against the Cleveland in favor of keeping the Windsor around was weight. The 351C had a good 90lbs on a 302W, and with passenger cars trending down in dimensions and weight making a 302 variant ala Australia just wasn’t desirable, so they just let the 335 engines live out their amortization cost in trucks. Still, I wonder why the Cleveland canted valve head design never got transferred over to the 302 at any point during its performance renaissance.

The Romeo VS Windsor modulars aren’t near as different between Windsor and Cleveland 351s. A few fastener differences, some casting revisions, individual camshaft caps, presssed sprockets, 8 bolt crankshaft and 13 bolt valve covers about covers the differences, but the engineering was identical, and everything important directly interchanges between them – heads, cams, water pump, oil pump, timing components, valvetrain, bearings etc.

Yes, stopping the 351W production and converting to 351C would have not amortized the costs. Which is why I said above that Ford must have figured that it was more cost effective to keep the 351W line running at Windsor. With a little bit of context from the history, the two 351s at the same time makes some sense. That said, better long term planing by Ford, probably could have had a more cost effective, less complicated result. As much as I like the 351C, it probably would have made more sense in the long term for Ford to have just start producing a copy of ithe 351W at the Cleveland plant, or at the very least used the 351W block with the Cleveland style heads.

Matt, I think the added weight was a factor, but a 351C to 351W wasn’t that big of a difference. Ford could have adapted the canted valve 335-series head to the 351W, like many have with Clevor conversions, but the head design wasn’t the best for emissions. The canted valve arrangement required the pistons to have valve reliefs for clearance. This pushed the ring pack further down on the piston. This extra space, created and area where hydrocarbons could form, which increased the emission output. It was a great head design, but it was designed more for performance than clean burning.

I mean weight vs the 302. The 302 was to become the top engine in downsized passenger cars in the 80s and it simply made more production sense to use the architecturally identical 351 Windsor for trucks and early panther cars since those wouldn’t really benefit with the Cleveland’s potential for their purposes anyway. Doing the Aussie method of destrokeing it to a 302 wouldn’t shed any weight, and as it turns out the tooling for the low deck engines was in Geelong by this point anyway, so the next possibility using existing domestic tooling would be a “302M”, which would be a real lump.

So in that sense I’m not really pondering why a 351 Clevor hadn’t been done, but instead a 302 Clevor (ala Boss 302), using the Cleveland head design in a H.O. performance application. The real life H.O. even has valve relief pistons, so I’m not sure it would have done much worse in emissions.

I did follow you on the 302 being far lighter than a 351C. I just made mention that the 351C wasn’t that much heavier than the 351W. Sorry for not being more clear, I am on the same page as you. 🙂

As for the pistons, the 302 HO had valve reliefs, but not like the 351C. Due to the canted valves, the reliefs are quite a bit different on a 351C compared to the inline valve 302. See the 351C piston below and how the relief moves the top ring grove quite a bit lower on the piston.

I know I have joked about the 400, but having had a lot of seat time shuttling big Fords in 1971, the difference between the 351s and 400s was quite palpable. Much better off the line push. We used to race stoplight to stoplight, and the 400 was an easy win compared to the 351.

Thanks again Vince for this excellent concise history of these engines. I hope it becomes as popular as our Ford 4.6 and FE posts, which get a significant number of views every day, from Google searches.

These engines were well made and could make a lot of power when tuned properly, plus they had a unique mechanical sound due to the splayed valvetrain when compared to the Windsor-based engines with their inline valves.

A friend had a 2-bbl version in a ’73 Torino that ran quite well when the timing was adjusted using vacuum vs. the deliberately retarded factory specs. That, along with some better spark plug wires and the usual upgrades (coil, plugs, judicious carb tuning, etc.) made for a smooth, torquey powerplant.

Another friend in high school had an honest-to-goodness 351 Boss engine that had been extensively built, and the receipts for all the machine shop work. One of the failings of this engine as noted was the oiling system. His engine had a fix that re-routed oil from the lifter feeds back to the main oil gallery via external tubes at the back of the block – apparently this was a “thing” racers did to fix the issue. It also had a Lunati roller cam in it with around .5″ of lift…at idle, the open hood and trunk lid would shake violently from side to side. It was built to handle over 7,000 RPM and the sound it made on a full-scream run nearly scared the life out of me…simply awesome. Some months later, it seemed down on power, so the friend took it to shop in the area with a chassis dyno – it was making 400+ HP even with a dead cylinder (yes, you heard that right – 400+ HP on 7 cylinders)…

I started high school in the mid ’80s, and few of the V8 cars of this era were running as they would have originally in good tune on high octane leaded. There were still quite a few of them in the hands of teenagers though. My older sister had a friend name James who’d let me drive his big ’74 Ford when I was 14 years old.

Fords had never been my interest, and it is funny how confused we all were by their engine offerings. It seemed like most of the ones I drove before getting my license had 390s, but James’ Custom 500 had a 351-2V. He called it a Windsor, and explained that the Cleveland was what Ford called 351s with 4 barrel carburetors. It turns out that he was wrong, but it made as much sense as what Ford actually did. Thank you for making this topic as clear as it can be!

Great write up! As a side note, Ford Motorsport, imported and sold the 302C heads for a all too brief time in the mid 80’s. There is a close out ad, by Colley Ford, a well known Motorsport dealer in the November ’88 Circle Track magazine I have. $500 A PAIR. I cry everytime I see that ad.

You are correct that Ford Motorsports did make a cast iron head that was similar to the 2V Aussie head. It was sold over the counter by the SVO parts program and used part number M-6049-C351 Like the Aussie head it used a the small port 2V and a closed “quench” style combustion chamber. However, this head was cast for a 351 engine and so it used larger 62cc combustion chambers over the small 58cc heads from the 302C.

While I don’t have the numbers available, I’d also suspect the SVO heads flowed better than the Aussie 302C heads. While the 302C heads share the 2V port design with other heads, flow tests show that they flow less air than the other 2V heads.

$500 for those heads was a good deal. They are very rare today, and and would be a good head for a street motor build without resorting to aftermarket heads.

Great article as I said the other day, Vince. This clears up much of my confusion from my early teenage to high school years when these engines were still around.

My neighbor had the 400 in her ’74 LTD Brougham. I drove it a couple of times and it did not seem that much different from my 351W-2V in my ’73 LTD. I attributed it to hers being a Brougham 4 door compared to my Non-Brougham 2 door hard top, figuring hers weighed more than mine. However, the further de-smogin’ for 1974 was likely the reason.

Hers always did strike me as having a little more grunt from a dead stop, though.

As an aside, I could use my LTD’s door and ignition key to get in and start her car! I surprised her with that one day when I washed it for her. She went to get her keys to have me move it, and when she came out, I already had her car moved! The separate trunk keys however were not the same.

Thanks Rick. I am not surprised by your account of the 351 vs 400. Some of it was no doubt the weight difference. Typically a Ford 400 was a fair bit quicker than a 351 in identical cars, but it wasn’t always the case, depending on years, options, etc.

We also have to keep in mind is that there was a wide level in the quality control on these cars in this era, unlike today. So two identical cars could have a fair bit of performance difference just based on how well each was built/tuned, A lot of cars had bad tunes from new, as they were poorly setup by the factory and/or dealerships. On top of that, as they got older and more miles on them, the performance could drop off significantly if the owner didn’t keep the engine in proper tune. It’s amazing how much “power” you can find, when you give a car from this era a proper tune-up.

In January of ’75, Motor Trend did a big comparo of all the PLCs on the market. The Elite and Cougar they tested had identical 351 powertrains,

but I’m unsure of W or M. I remember poring over the spec sheets trying to find any differences. There weren’t any, right down to tire sizes and gear ratio. One strange fact is that the Cougar was somewhat lighter than the Elite, but much slower. I do question the veracity of the info 4 decades later. Did they actually put each car on a scale or just take the manufacturers word for it? Both of them, did however, beat out the 318 Charger which MT described as “having become senile”.

I don’t have this road test in my collection, so I’d be interested in reading it. I think this is likely a good example of two identical cars having a big difference in performance. Maybe one was a 351M and the other a 351W, but most magazines from that era didn’t seem to distinguish the two. And on paper, they should have been pretty close even if it was a 351M and a 351W. Of course the other factor is the accuracy of the tests. I don’t know how often they actually scaled a car, but I think it’s safe to assume that the Cougar and Elite would be pretty darn close to the same weight.

I have an old family friend who worked at a GM dealership during this time. He was a tune-up guy and told me how badly some of the cars ran when they came off the truck. He mentioned that some cars really needed a lot of work to get them to run properly even when new.

Very interesting. Over the last couple years, I did an engine build on a Ford 400 in a 1979 Lincoln MK V.

The premier aftermarket stuff for these motors is the TMeyer 434 stroker kit, which adds 0.35 in of stroke to the already long 4 inch stroke. Added to this were Australian heads, high performance lift rockers and loads of other go fast stuff.

I never do what the other guy is doing, and I went for torque and reliability. A 335 can make loads of power but not for that long in my opinion. I went for a relatively mild cam but still rad enough to give the desired slightly lumpy idle and the high perf noise I can’t describe. With a small Holley 650 and stock exhaust manifolds I got 330 real wheel horsepower and 380 lb/ft of torque, with 300 available by 1300 RPM. These are real, verified horsepower, too.

I also installed a GearVendors overdrive unit which makes the C-6 a six speed. The result is stupid fun. If you are cruising 50 km/h and stomp it, the rear wheels light up, it makes all kinds of rumbly go fast noises and scares babies in prams. It’s a total grin-fest.

The best part is it will also reliably burble along at 1000 RPM all day and that it uses 94 octane pump gas and likes it just fine.

I recently rebuilt the suspension, replacing all the 30 year old parts, adding new springs, coil over shocks and sway bars. Got the steering box rebuilt and modified and it transformed the way the car drives. It now has the suspension to handle the power.

The stock brakes are just fine and a real testament to the design in 1979.

VinceC, Christmas came early this year—I had figured that Part Two wouldn’t appear until perhaps sometime in the New Year.

This is an informative delight, and your careful & thorough work really shows. A Ford Guy really learned a lot from this (and he’ll be returning to it again and again).

I had a very personal response to the story of the cracked blocks, being that my father was Process Engineering (quality control, if you will) guy at the Cleveland Foundry at that time. I wasn’t happy to hear of the defects cropping up, but I’ll admit being cheered to hear that it was only at the Michigan Casting Center, and not in Cleveland!

The MCC was “Flat Rock” in Ford Shorthand, and occasionally Dad had to make the 2-1/2-hour drive to F.R. in SE Michigan to confer with his counterpart there (“I’ve gotta drive to Flat Rock on Friday; they’re having a casting problem with XXXXX”).

Again, VinceC, highest compliments to you for putting this together. I can’t think of a stone left unturned. I’m sure that, as Paul has indicated, that interested non-CC Googlers will be showing up in the neighborhood soon!

Thank you very kindly George! It is interesting that your father was a Process Engineer at the Cleveland Foundry. I don’t know of any issues with Cleveland Foundry castings, so they must have done a good job. From what I know, MCC had problems with the cores shifting which made some of these engine blocks susceptible to cracking in the lifter valley. Apparently lots of the engines were replaced under warranty as a result.

It’s also similar to Geelong that had casting issues due to core shift with the second batch of NASCAR blocks. Although in that case, the “bad blocks,” while not up to racing standards, were good enough for production cars. This is why some production Aussie cars ended up with the racing engine block.

Friend across the street made good money as stereo installer and bought a lightly used ’77 Cougar XR7 with balance of warranty (gee, 12,000 miles,

weren’t they generous?!) . At 15,000 miles the block cracked. LM dealer told him to pound sand.

It also dropped a valve and buggered a head, so he had to eat a long-block himself.

This cements my opinion that Ford Australia was a gearhead paradise during the 70s. Many growing countries who got old US tooling got outdated tooling. Australia got our best stuff while we replaced it with boat anchors.

In all seriousness this is a wonderful series! I was born too late to have a deep understanding of these engines and really just knew the basics like W vs C vs M vs 400 and 2V vs 4V, but how/why/when compression ratios changed, what blocks were best and Australia’s unique efforts on this engine family always were mysterious and full of conflicting information. My almost first car was a mid 70s Cougar with a 351, and I felt so lost trying to figure out which version it was and what I could do with it on a high school budget, it intimidated me right out of it(that and the rust).

Ford was frustrating with their engines, it always seemed the Chevy guys could just throw in a cam headers and intake on their 350 and have a strong street machine, but if you get the wrong year Ford you’d need, heads, pistons, rods maybe a block in addition. “At least I have a lead on built transmission I can use….. wait M uses a different pattern??? Son of a…”

Re The Pantera. In about March or April of ’74, Motor Trend had a clip out form that you could send to LM manager Ben Bidwell as a protest to keep it in production, as Ford had announced they were dropping it soon. My 14 year old self sent it in and actually got a form letter reply from said exec. Gist was don’t worry, the supply line was long and would last well into 1975. Translation, it’s a gas crisis and we can’t give these things away.

Looking back, what good would keeping it around have done? There was no suitable

smog legal engine for it any more. Could you imagine a Pantera with a 302, or a 351-2V

in any iteration? That would be as much of a joke a 351-2V Windsor-powered Bricklin, and an even bigger joke than the Cali-only 305 Corvette in ’81.

Ford made 335-series engines in South America, too. Brazil (Brasil) I think. An odd yet strangely familiar cubic-inch displacement, too.

‘Course, Ford was still casting the ancient “Ford Y block” in Brazil in ’75 and maybe later.

Ford made a 335 cid engine based on the “Windsor” small block, that was used in Mexican and South American markets. Perhaps this is what you are thinking of?

The sole engine offering in Venezuela market big Fords was the 400. Not sure if that’s because they had the tooling for it or it was imported.

Note in ’75 it was still Galaxie and the HP was still the ’71 gross figure.

The car it went into.

Excellent article. One important limitation for the 400 was the carb and intake choice. Ford trimmed pennies by opting for a small 350 cfm 2 bbl carburetor which was at maximum flow at a measly 3500 rpm. A common modification is either an aftermarket aluminum 4bbl intake, or, if cost was an issue, a Holley 500 cfm 2bbl on the stock iron intake manifold. Of course the 4 bbl set up is more powerful and more efficient. Combine that with an aftermarket adjustable cam timing set up, and one can easily add significant mid range and top end power, with improved throttle response.

I have a 400 in a ’77 Mercury. Even stock, its smooth, torquey and well suited for relaxed, effortless driving. The 460 was an option in my Mercury. I have one in my 77 Lincoln. I feel there’s very little to gain with a stock 460 over a 400. On paper, the 400 gives up a lot to the 460, but for real world driving, in stock form, they are very close, which says a lot for the baked-in virtues of the 335 architecture .

Great point about the small 2-bbl carbs. The 400 was strangled by these small carbs fairly early in the RPM range. Even with the stock low RPM tuned cam, a 4-bbl carb really wakes up a 400 by allowing it to breath at higher RPM.

The 460 had a timing gear set retarded 2 degrees by ’72. Compare the same year and car say a Lincoln Mk IV, and there was no comparison the 460 was the better engine. Today, its stupid easy to build a stroker crank 460 and there are a good number of street and race heads available and very affordable too.

The 1974 Ford Gran Torino Elite I drove in high school was equipped with a 400 2V. The car was capable of melting the right rear tire under certain conditions, a raucous and very juvenile activity I engaged in often. It did have tremendous torque and moved that 4200lb Elite with some fairly decent authority, considering we are talking Ford’s Malaise Era here. I regret I never had the chance or funds to convert it to dual exhaust, put some better gears in it, and maybe a few engine mods. It would have been a real runner then. It stood up very well to my knucklehead, teenage driving abuse, as it was equipped with the tough C6 transmission and 9 inch rear end.

Years later, out of school and making better money. I test drove a 1979 Lincoln Mark V with the same 400, rated at 173hp. (The Elite’s was rated at 170; go figure.) In that 4800lb Lincoln and all the extra emissions controls the Elite did not have, that 400 felt overtaxed and overburdened. That Lincoln seemed to spend most of its time in 2nd gear. I did not buy it because I found its performance too torpid to the point that the enjoyment of the car would be blunted. I should have bought it and held onto it. It was one of those rare Cartier Designer Series, finished in that champagne color with the burgundy accents. It was gorgeous. You know, hindsight being 20/20 and all.

ford should have stroked the 351 Cleveland and had 302w 351c and stroked 351c/400