curbside photos posted at the CC Cohort by trabantusa

curbside photos posted at the CC Cohort by trabantusa

(first posted 12/12/2013) The Great Aerodynamic Fever hit its peak in the years 1932 – 1934, when the streamlining contagion suddenly flared up on both continents. Infected designers and engineers would awake one day and find that they were suddenly incapable of drawing straight lines anymore, especially vertical ones. One of the earliest victims was Raymond Loewy, a French engineer who moved to the US and got his start here designing department store windows. He soon put his affliction to good use.

image source aldenjewell

image source aldenjewell

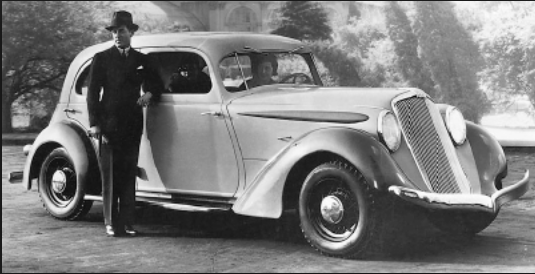

Rather than seek a cure, Loewy decided to exploit the phenomena, and opened an industrial design office in 1930. One of his first clients was Hupmobile, one of so many small independent automakers. He cleaned up their 1932 models a bit, but the big leap forward was the 1934 Hupmobile “Aerodynamic”, Loewy’s first clean-sheet automotive design which arrived the same year as the ill-fated Chrysler Airflow. And although the “Aerodynamic” was less radical than the Airflow and relatively more successful, it still wasn’t enough to save Hupp. Apparently American consumers had a natural resistance to the streamlined contagion.

Not surprisingly, the Hupmobile was named after its founder, Robert C. Hupp, an engineer who had worked with both Ransom E. Olds and Henry Ford striking out on his own in 1909. And like so many founders of new companies, he eventually got into it with his investors, and walked away just two years later. Hupmobile survived, and prospered during the go-go twenties, and hit a sales peak in 1928 of 55,000 cars.

But the Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Depression severely impacted Hupp, like so many independent brands. So they looked to Raymond Loewy, in the hopes that he could replicate the success he and other designers had in making consumer products look more attractive by enclosing their working parts in a streamlined envelope. If it worked for toasters, why not cars?

Hupp thus became Loewy’s first automotive client. Wisely, Loewy did not push the (aerodynamic) envelope too hard with his 1934 Aerodynamic Hupmobiles, available in six cylinder and eight cylinder versions, and in coupe and sedan body styles.

From the rear, the Areodynamic Hupmobile is only about a year ahead of such mainstream cars like the Ford, which adopted similar design language for 1935, except at the front.

Unlike the Airflow’s blunt front end and waterfall grille, Loewy went with more traditional design cues up front, but faired all the elements together. The result is bold, dynamic and advanced for the time, but certainly not revolutionary, like radical and grill-less Tatra streamliners of the same vintage.

Loewy’s approach to streamlining the traditional front end is somewhat similar to that taken by Philip O. Wright with his 1933 Pierce Sliver Arrow, shown at the 19933 Chicago Exposition, although the Silver Arrow was more radical in the treatment of its front fenders and the lack of running boards.

Did it have the desired effect, sales-wise? Well, sales did improve, up to a whopping 9420 for 1934. That also included non-Aerodynamic models, but undoubtedly the new look generated a bit of badly-needed foot traffic for Hupmobile. 1935 sales rose to 10,800.

Although the cars looked smooth, the company was in total disarray thanks to another fight for control of the company. By 1936, Hupp was in ruins, and shut down for an extended period of time.

Hupp had one final act of desperation before it shut down for good. General Manager Norman De Vaux bought the body tooling from the late and great Cord 810/812, and adapted it to Hupps rear wheel drive chassis, with a new nose styled by John Tjaarda, another of the early infected designers. But Hupp couldn’t get the Skylark into production, and made a deal with also-floundering Graham to have them build the bodies for both companies. (Graham CC here)

That Cord design must have been doomed, as it took forever to get any kind of production going by Graham due to tooling problems. Production didn’t begin until 1940 (!), and the supercharged Graham outsold the Hupp Skylark six-to-one. But it wasn’t enough to save either company, and Hupp shut down for good in July of 1940, having sold some 300 Skylarks.

This 1935 Hupmobile is a great find by trabantusa, who posted it at the CC Cohort. I was infected by the aerodynamic contagion at an early age, and seeing a car like this triggers symptoms; writing them up, in may case.

Paul,

Thank you. From the day I first read about these cars, at age 12, and looked at the line drawings in the book, I’ve always wanted to see one.

And never had.

OK, its only a photograph, and not actually being able to stand on tiptoes and look in the driver’s side window; but I’ll take it. Gladly. I finally get to see what one of my childhood obsessions looks like.

By the way, someday it would be fascinating to have someone do the research on Norman DeVaux, who was one of the more fascinating minor players in the automobile industry during the 1920’s. I believe he was involved with the Ruxton (looked very much like, and was introduced just after, the Cord L29), the Continental four cylinder automobile (same idea that Willys attempted with the Americar in the late 30’s), then the DeVaux (the Continental, rebadged) before working his way into Hupp.

A manipulator, wheeler-dealer, the guy who could dream up everything . . . . . as long as somebody else was providing the money. Now that I think of it, he was kind of the 1930’s version of Malcom Bricklin. And was no more successful. But he did leave a mark, if you know where to look.

The Ruxton used a continental straight-8 flathead. The ’40 Hup Skylark SHOULD have modified Tijarda’s front headlight design, trashing the dull- teardrops and using a version of those pod-like headlights on the ’38 Studebaker(whose lenses mimic-ed the slant-back of the grill vent on the hood), that were one yr only, because they didn’t fit the grill/front of the ’38 Stude. Also, the Hup & Graham, SHOULD have used a longer wheelbase, giving the luxury & “value” of the size(length) of the Cord. Cord didn’t have (and thought he couldn’t afford) a huge stamping press, so the Cord sedan bodies had 13 pieces in the top–acceptable for a luxury make, but expensive for a mid-priced car like the Hup, who had to develop jigs to get those 13 pieces welded together, when GM or even Budd would have had a single, stronger, stamped, “turret-top” piece. I LOVE the Sound of the name, “De Vaux”. I’ve seen both types, in real life,–Skylark/Hollywood, and each has enough room, under the hood, for a Volker DOHC, crossflow, electron head that would have easily made another 50-80Hp on top of the stock 110, making a V-8 like the Cord had, un-necessary. Volker made alloy DOHC heads for straight-8 and V-12 Packards that were put in boats in the Detroit area for “racing” & stuff during Probition) and some found their way into race cars and a few street-cars, even in the 30s.

Are we not men?

I wonder if there are any Volker heads around. Probably wouldn’t fit a postwar Packard Straight 8, tho.

What really would have modernized the Skylark/Hollywood is a much larger rear window, perhaps a 3-piece design similar to the Cadillac 60 Special with chrome divider bars. And it may have maybe reduced the amount of separate steel pieces that had to be welded in as part of the roof at the rear portion. Agreed freestanding headlights in pods were becoming dated by 1940 when grilles were getting wider and fenders getting fatter when designers started integrating them into the fenders like Cord did, even though not hidden.

I love when we revisit the ’30s design revolution. I can’t quite say this car is beautiful, but it is fascinating, especially the treatment of the headlights.

IMHO, I think the headlights kind of suck, COMPARED… to using ’38 Studebaker pods. Check out ALL the ’38 Studes, and see if you don’t agree. Studebaker had used those for one-year only and then abandoned them, so they also would have been cheap to acquire,–maybe 10 cents on the dollar. The ’38 Stude pods on the Hups & Grahams(Skylark & Hollywood) would have sold many more units than the teardrops used, that manufacturers were moving away from, because of “Continuity of Design,” and, “Flow”…

Great find – all new to me.

Even at this distance in miles and time, that 1934 car looks distinctive, modern and pretty sharp.

I guess the brand died not because of this car but due to the competition from the Big Three and Hupp’s inability to meet it.

Hupmobile had the same problem as all the other independents – too small to compete once times got tough.

In 1929 everybody was going great guns. Well, almost everybody. Hupp was unique in that their 1928 sales were better than 1929 – not a good sign when you’re already starting to go down at the very height of the Roaring Twenties.

By 1930 the shakeout had started. You had the Big Three: GM, Chrysler and Ford (in that order). Sheer sales muscle who could overwhelm anyone else.

Then you had the independents who were either healthy or had enough resources to give them a good chance to ride it out: Studebaker (who handled the Depression with incredible stupidity – they could have been in the first group), Nash, Hudson, Packard, Willys.

You had a third group who was marginal, but still had a big enough customer base to possibly ride the Depression out, if it didn’t last too long: Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg (who did surprisingly well until the ’34 model year crashed and burned), REO, Graham, Pierce-Arrow.

And there was everyone else: Stutz, Hupp, Marmon, Peerless, whatever was left of Durant’s empire, etc. They would have probably gone under even had the Depression ended before the 1932 election. The industry had matured enough that the small size limit for being a viable player had gotten much higher.

Size matters. When you’re selling 40,000 cars in a good year, you’re going to be hammered by Oldsmobile or DeSoto alone. Much less facing the resources of the rest of the parent company. 1930-34 was the second major shakeout in the auto industry, preceded by 1920-22 and followed by 1953-58.

Sales of Jordan were also declining even before the 1929 crash. Many of the smaller independents competed in the medium-price field, and sales in that segment were declining even before 1929, if I recall correctly.

Very graceful and elegant,I’ve never seen one and have only seen one in a magazine.I like that Pierce Arrow also.

Wow, that illustration of the Huppmobile with the dirigible in the background is awesome(talk about a phallic symbol) !

Really cool find. I am surprised that nobody has mentioned the fascinating windshield treatment. The entire car is certainly inventive, and the way the headlights are faired into the body is quite unique. I saw pictures of one of these years ago, and I still can’t decide whether I like the front or not. That front bumper, however, is a pure delight.

As for the Skylark’s problems, I have read that they stemmed largely from the fact that the Cord body was never designed for serious volume production. The body dies made small pieces that had to be joined and filled by hand, and were production nightmares. The other problem was that because of the switch from the fwd Cord to the rwd Hupp, the body sat much higher on the frames and made the cars look very awkward.

Like Syke, I always enjoy a dip into the prewar stuff.

What wasn’t mentioned is that after missing the 1937 model year Hupp made another attempt at a comeback in 1938. The car was quiet, conservative, kinda reminded you of a 1937 Buick – and it came out just in time for the 1938 Recession. Just as the country started to think the hellish times were over, it fell back again. Not enough to drop the country back to 1932, but bad enough to put the end to A-C-D and Pierce-Arrow, and mortally wound Hupp. And did almost as much damage to Graham. The Sharknose was a complete bust in the market, a worse sales disaster than the 1934 Auburn.

The Skylark/Hollywood was an absolute last, desperate throw of the dice. I’ve read that only 53 Skylark’s were made, and whether they were salable models or just pre-production prototypes is open to discussion. Just the same, they only made a bit over 300 Hollywood’s, and Graham retreated back into war work. At which time Joe Frasier took over and they became part of the Kaiser-Fraiser empire.

“As for the Skylark’s problems, I have read that they stemmed largely from the fact that the Cord body was never designed for serious volume production. The body dies made small pieces that had to be joined and filled by hand, and were production nightmares.”

Correct. If I recall, the roof alone is seven different stampings that have to be assembled in a jig and soldered together. The technology to make a panel that large was newly developed by GM in 35. Cord didn’t have that kind of money.

Hupp subcontracted it’s body building to a company in Grand Rapids, Mi. The story goes that the firm in GR was charging Hupp more for the body than what Hupp wanted to charge at retail for the finished car. So Hupp turned to Graham, which was also desperate for a new model, and that is how Graham ended up making both the Skylark and Hollywood.

As for the Cord not being designed for volume production, I’m afraid E. L Cord put way too much priority on “halo” models. Gordon Buehrig did a refresh to the existing Auburn line, but the only model that received a complete new body was the Speedster. The bread and butter Auburns only received a new radiator shell and fenders, grafted onto the previous generation models. The refresh worked for a year, then sales dove and the Auburn line was killed.

Buehrig was initially charged with designing a junior Duesenberg, but he took a pragmatic approch, designing something very close to the final Cord design, but using off the shelf, reliable, Auburn drivetrain. Someone up top had the idea to make it front wheel drive, which caused a problem and cost cascade as that required development of a new V8 engine and the abominable preselector gearbox.

Delays caused by the new engine and trans pushed production back to the point Cord was afraid of missing the publicity of the New York auto show. To qualify as a “production car” for the show, 100 810s were built by hand in the experimental building behind the HQ building in Auburn.

The car was a huge hit at the show. Orders poured in. It still wasn’t ready for production however and many of the orders were cancelled as time passed. Meanwhile, most of the 100 hand built preproduction cars were deemed unsalable and scrapped.

Stunning the amount of money wasted on the 810 program, especially considering the company was fighting for it’s life.

When customers finally did receive 810s, they soon discovered the drivetrain was still underdevloped and troublesome.

The Auburn Cord Dusenberg museum has a set of an 812, Skylark and Hollywood sitting side by side so the lineage is easy to see. Another museum, directly behind the ACD museum, in the old experimental building, has the remains of one of the preproduction 810s that had been used as landfill, then dug up 50 years later.

The pic is of an early design for the Hupp version, which was rejected as looking “too much like a Cord”. For my money, it’s much cleaner then what finally went into production

Part of the Graham plant still stands at 8505 W Warren in Detroit. After Graham closed, Chrysler bought it and built DeSotos there for much of the 50s.

It was always saddening at the way A-C-D failed, especially as they were riding out the first part of the Depression way better than anybody should have. Back in the early 30’s, Auburn seemed to have a cachet as “the car to be seen in”, and about the closest modern equivalent I can think of were the late 70’s/80’s BMW 3-series. Not a huge seller at the time in comparison to everything else, but a definitely sign that you were making it very nicely.

The 1930-32 models seemed to sell very well (afraid I don’t have hard numbers), while there was a dip in sales for 1930, the 1931 numbers outdid 1929! Which no other car company could claim. And the ’32’s must has sold decently well, because I’ve seen more ’32 Auburns at shows in my life than any other year. Something went very wrong between the ’33 and ’34 model years, as I’ve read that the ’34 was a failure in the marketplace.

By the time the ’35 was facelifted, it was that famous front end that you’ve seen on the 851 and 852 boattail speedsters coupled with the earlier body. Which really didn’t look all that good in the 4-door sedan.

Like you mentioned, E. L. Cord’s biggest weakness was a love of halo models, and an almost complete ignoring the plain old 4-door sedans by the mid-30’s. And, he was getting disinterested. Aircraft had his fancy by this point, and he was ignoring the automobile company.

Ive seen the insides of a 810 I caught one being restored at a museum here and the spares car they had was in a dismantled state, very crudely engineered but a beautiful car.

The two-piece front bumper is quite elegant as well – although maybe not very practical in a minor front collision.

Don’t forget the Hupp/Graham cars were on a shorter wheelbase,–a big mistake, I think. Some small manufacturers had not only volume problems but labor troubles(Hupp), and I believe the coming increased taxes on business, the O’Bama of the era, FDR, wanted for 36-37, deepened the Depression. The Studebaker Chief killed himself, thinking he had ruined the company, but they spun-off the “Cost-no-object” Pierce-Arrow (and didn’t use Pierce’s superior straight-8, and V-12s, where the build could have been cheapened slightly if put in Stude “Presidents”[–their ‘Caddy’]), –hired the “Hot” French designer Raymond Lowey to make a “LandCruiser” for Dictators & Presidents, and soldiered-on. –What a Name for a car in the 30s–a Dictator,–a mid-line Studebaker!

Mae West had a primrose yellow ’41 Graham Hollywood. It sat in a body shop lot on

3rd Street, east of La Cienega in West Hollywood during the late ’70s. I used to drive by it frequently and imagine her behind the wheel during the ’40s. In the late ’60s, when still a young lad, I had the extreme good fortune to own its sister car, but mine had been street-rodded with a 392 Hemi, high-banded pushbutton Torqueflite, duals, an interior from a mid-’60s T-Bird, Keystone mags and 14 coats of black lacquer. We were the terror of the hills around Blawenburg, N.J. for a whole summer.

Even 70 years later, the lines of this car are stunning. To think that it appeared in 1940 must have raised a lot of eyebrows (or 1937, if you start with the Cord Beverly sedan). We drove it to New York once, parked it in a garage off 57th Street, nose out, and when we returned and opened the front (suicide) doors to mount up and drive off, a businessman in a well-fitting suit, and carrying a briefcase, walked by, glanced our way, stopped, backed up, took another look and asked us, “Iss dis a Cherman kar?”

It was that spooky.

They turned Mae’s into a limo by cutting the car in half an adding a foot to the frame and body, then putting a diamond-shaped window in the extra space.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

Knowing little to nothing about Hupmobile, I found it fascinating to read about how a small independent put forward such a bold design, at the same time bringing Raymond Loewy into auto design for the first time. My only knowledge of Hupmobile comes from hearing Al Pacino’s character in “Scent of a Woman” ridicule a car as being a “Hupmobile” and having to look up what a Hupmobile was.

A timeline (with photos) from Hupmobile to Avanti would be interesting to see.

I believe that the feature car is the same one that I saw at LeMay’s yearly show a few years ago – note the dual exhausts.

Here’s a rear view….

Looks like it’s sitting on an air supension too, given how low it is there .

This ’35 Hup must have been the inspiration for the pre-war Opel Kadett, whose headlamp treatment I had always considered unique. And less than elegant.

In the photo of the ’29 Hupmobile, if the style of the car didn’t give away the era, the model’s cloche hat would!

“And like so many founders of new companies, he eventually got into it with his investors, and walked away just two years later.”

Hupp set up his own company using his initials (R.C.H.) in Detroit 1912 to build the car that he wanted to produce at Huppmobile – a reasonably priced ($700) car. Initial sales were promising – 7,000 in 1912 and orders for 15,000 cars for 1913. The R.C.H.’s reputation, however had been tarnished from hasty manufacturing to meet those orders, and company president Charles P Seider (who took over from Hupp in 1913) decided to close down production in 1915.

Another aerodynamic contemporary of this Hupp is the 1934 Studebaker President Land Cruiser, a low-volume halo car that also appeared as a sort of companion to the Pierce Silver Arrow at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair.

These two make quite a contrast, with this early Loewy designed Hupp appearing more European (go figure. 🙂 ) Where the front of the Hupp contains most of the drama, the Studebaker’s action is mostly out back.

From the front

I do not believe I would ever kick that car out of my garage! You gotta love that three-piece windshield. That alone makes me drool!

Great article. Here is a good look at a unstylized photo of perhaps the most interesting aero Hupmobile – the coupe. Notice the oddly-shaped window opening.

The Coupe is the real stunner .

-Nate

+1 on that coupe.

RE: Hup Coupe — Wow, very punk rock in my eyes. Wish it was my daily driver.

Great article, Paul. Another car/ series that I had no idea about, and my Hupmobile knowledge is next to non-existent. I do think that, visually, the grille is a bit too big for the front area…….maybe too high? But the car is very strikingly designed, and it’s always interesting to see and hear about what the independent companies were doing, before they went under.

Oddly enough, I had thought of Graham, RIGHT before the paragraph where you mentioned them. It’s interesting that the Cord design had essentially crippled various companies, because of the expensive and inefficient tooling. No doubt this had some impact on the Big 3 analyzing production processes to make sure that they didn’t repeat the same mistakes.

The Skylark was a great looking car, though. It would have been interesting to see a company succeed with the Cord design……even the ’66 Toronado needed a few more years to be more conventional in design to really appeal to a wide audience. If one considers the original Toronado, has the Cord design ever actually been a money maker for any company?

That Hupp was influential. The distinctive headlamp faired into the sides of the grille caught designers’ attention. Opel (GM) copied it for their ’37 Olympia, Renault copied Opel when they did the ’38 Juvaquatre and the Russians also copied it (1940 KIM 10 & 1946 Moskvich 400, the latter a complete Opel rip-off). I doubt Raymond Loewy ever saw a penny in IP rights from this design gimmick. But that’s good design for you – people will just copy it.

Ah – somehow I missed your post. Pictures of all of those below.

A local classic car hire firm has several Huppmobiles though they are twenties models not the later Loewy designs,

I quite like Loewy designs and still drive one of his later efforts.

It was only a few years ago that I became aware of the Loewy designed Hupmobiles. I’ve been a fan ever since!

In these times during America’s automotive history, Nash;Hudson; Studebaker; and Packard all were in decent financial health and George Mason’s dream of an American Motors was almost 20 years in the future. Meanwhile, six interesting marques – Auburn, Graham, Hupmobile, Willys, Deusenberg and Cord – all were at various heights on that slippery slope of falling sales leading to bankruptcy. All they needed was Son of Billy Durant to come along, corral all six into an umbrella corporation and convince financial backers to breathe life into the new entity.

Imagine, the combined output of these stylists, engineers and production facilities collaborating for the survival and benefit of each marque! This could have been the REAL American Motors.

Interesting to contemplate.

I love the reposts of old articles, because it’s fascinating to read the comments that followed. This was definitely one of the better discussions we had on a marque in quite a while.

Someday I’d love to see an article on the 1934 model year in the American car industry. Something about that year had almost every manufacturer hitting on all cylinders when it came to car design. A beautiful combination of the prior ‘antique’ automobile design updated with aerodynamics. For a year or two, this gorgeous combination held sway.

Then by 1936 everybody was evolving towards what we consider the WWII design era.

I am surprised no one mentioned how the Hupp influenced some of Opel’s late 30s design – the below is a 1939 Admiral. That front headlight/hood merger could also be seen on the smaller Kadet Olimpia (and later on the Soviet Moskvich 400 which was a copy of sorts) as well as Renault’s Juvaquatre. So perhaps it was not THAT esoteric.

Opel Kadett

Moskvich 400

…and the Renault.

Some of these were quite long-lived, with the Moskvich being built from the prewar Opel Kadett sometime into the late ’50s, overlapping its’ replacement model as was the norm for Soviet cars, while the Renault Juvaquatre van and wagon were built alongside the (watercooled vertical inline rear-engined and thus not suited to such formats) 4CV right up to 1961 when both were replaced by the FWD, 5-door hatchback in its’ standard model, Renault 4L.

THANK YOU for adding these photos ! .

-Nate

Great-looking car and one I wasn’t familiar with at all. These early examples of streamlining are truly fascinating!

“Although the cars looked smooth, the company was in total disarray thanks to another fight for control of the company. By 1936, Hupp was in ruins, and shut down for an extended period of time.”

Those mid-1930’s managerial conflicts deserves an article in its own right!

“who handled the Depression with incredible stupidity – they could have been in the first group”

Studebaker, as a company, was remarkable in the number of stupid decisions they made before finally ending production. Bad business decisions, poor negotiating skills, incomprehensible styling decisions, you name it. Still they were the last of the independents, through sheer luck (Packard) if nothing else. Their run of bad decisions is only rivvaled perhaps by the last 10 years or so of AMC (Matador Coupe, Pacer, Matador sedan restyle).

”Infected designers and engineers would awake one day and find that they were suddenly incapable of drawing straight lines anymore,especially vertical ones” . We can say that they resume 90 years later because if we look at the best-selling vehicles,pick-up truck , they are only horrible sections of vertical wall. Sad to say but in terms of mobility offered to the public, the designs of this old aero era were more advanced than the modern generalist offer.

Early Hupps also had a unique approach to headlights. Eyes Aloft!

Graham somewhat survived, into the post war era. They were part of the Kaiser Frazer effort, and early Frazers were a Graham-Paige product.

Wonderful design. I would love to see one instead of just a picture. The back licence seems remarkably un aerodynamic.

Well done Paul. Very fascinating read for sure! Sad to think just how many American automobile companies have gone by the wayside over time.