(first posted 9/4/2015) Seeing this 1942 Hudson sitting for sale next to the road caused a panic of sorts. Painfully eager to stop and take pictures, I was up against the clock. It was the opening day of the state fair and my daughter had an entry to deliver with the submission deadline staring us in the face. Thinking about it, being up against the clock was the same problem faced by all the 1942 models in the United States.

Finding this Hudson fulfilled a pipe-dream; I’ve been wanting to find a 1942 model car in the wild for a while. That my long awaited 1942 model was from an independent make was icing on the cake. With my last CC being another independent (here), after a long drought of finding anything, it appears the tides have turned.

The Hudson Motor Car Company was founded in February 1909. It was named after financial benefactor Joseph Lowthian Hudson, an English immigrant who was 63 at the time of Hudson’s founding. Hudson was also the founder of Hudson’s Department Stores in Detroit. Derivatives of the Hudson Department Stores can currently be found as Target Corporation.

As an aside, Hudson’s niece Eleanor would later be known as Mrs. Edsel Ford.

While Hudson had ponied up the working capital, the Hudson Motor Car Company was founded by a consortium of eight businessmen experienced in the fledgling auto industry. Of the group, Roy Chapin, Sr. was the prime organizer and would be president of the company until 1923.

Except for a eight-month stint as Secretary of Commerce at the very end of the Hoover Administration, Chapin stayed at Hudson until 1936; he died that year at age 55.

Production began in July 1909 for models titled as 1910s. By the end of the year, the rapidly growing United States automobile industry had over 290 makes located in twenty-four states. The competition was fierce but buyers quickly realized Hudson had a good product as 1911 production volume would be 6,500 units, the seventh highest of all brands.

Hudson was never a low-priced car, however their introduction of the four-cylinder Essex in 1919 gave them an entry to compete with Ford and Chevrolet. Sales of the Essex were sufficient to propel Hudson to third place in sales by 1925.

Throughout the 1920s, Hudson built a reputation for its durable straight-six engines as found in its Super and Special Six series (1926 shown), cars that were viewed as a good value and possessing solid reliability.

In identifying a place where things started to fray for Hudson, 1924 would be a very likely culprit. Where the Essex had always been a four-cylinder car, Hudson decided to provide the Essex with six-cylinder motivation and move the Hudson brand upmarket. By 1930, this resulted in a single Hudson line, the Great Eight. Not so idealistically named, the eight-cylinder engine of the Great Eight had less displacement, thus power, than some previous six-cylinder Hudson cars and this eight was being forced to move a heavier car.

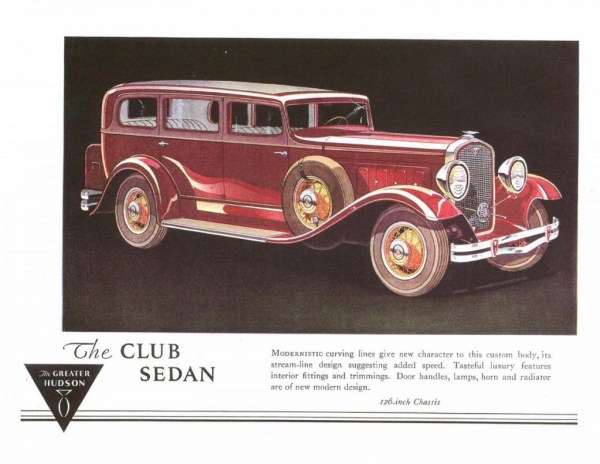

Hudson kept this engine for 1931 and 1932 in the Greater Eight (1931 model shown), but the timing was awful. The Greater Eight was a beautiful car, but eight-cylinder engines combined with stepping upmarket while the Great Depression was in full swing was not a recipe for success. Sales reflected it too; whereas Hudson had built 85,000 Great Eight’s in 1930, sales dropped to 23,000 for 1931, and to less than 8,000 for 1932.

Despite juggling names and engines, sales of Hudson branded cars weren’t that great for the next several years. In 1934, Hudson would again abandon six-cylinder engines, reserving them for the Terraplane, the successor to the Essex nameplate. The Terraplane itself would transition from being a standalone name from 1934 to 1937 to being a Hudson in 1938 and 1939, after it had served as an Essex model in 1932 and 1933.

For the most part, Hudson was able to keep its financial head barely above water for the bulk of the 1930s, primarily due to Terraplane sales. However, in an effort to keep sales going, it strongly appears Hudson cut prices to below the break-even point. Where they had scratched out a profit of just under one million dollars for 1937, the recession during model year 1938 (the cars seen in this advertisement) culminated in a loss of nearly five million dollars.

With the Terraplane name dropped for 1939, Hudson was back to being a singular brand. Sales climbed each year from 1939 to 1941, with Hudson making efforts to set itself apart as a brand. Hudson’s 20,000 mile endurance run in 1940, with an average speed of 70.5 mph, captured a new American Automobile Association record and helped bolster sales.

Anyone paying attention to world events in 1941 knew of the wars in Europe and the Pacific. While there were plenty of staunch isolationist advocates at the time in the United States, those sentiments evaporated on December 7 of that year. Upon Japan bombing Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, the United States officially entered World War II, waging war against both Japan and Germany.

At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, the 1942 model year was just getting underway, with Hudson having introduced their new models in September. These were far from being carry-over models from the redesigned 1941, as the 1942 Hudson had a number of positive changes and upgrades.

The most notable of the features for the 1942 Hudson was Drive-Master, their answer to GM’s recently introduced Hydra-Matic transmission. A combination of Hudson’s Vacumotive clutch and a series of servos, Drive-Master allowed nearly automatic shifting. Placing the car in high gear, the driver could accelerate to around 25 mph; lifting their foot off the accelerator prompted the car to upshift to high. Depending upon the mode selected, a car equipped with Drive-Master could be driven like a typical three-speed manual or have automatic clutching with manual gear selection.

Another significant change for the 1942 Hudson was the running boards being camouflaged. While still there, the doors were now curved to minimize their prominence. The running boards had ran their course and this was the first step toward their ultimately being eliminated completely.

By 1942, Hudson officially had the Traveler and Deluxe on the 116″ wheelbase, the Super Six on a 121″ wheelbase, and the Commodore Six and Eight, both on a 121″ wheelbase. Hudson brochures simplified this considerably, as the cars were lumped into the Six, Super Six, or Commodore Series.

Our featured car does not have a lot of chrome on it, but this Hudson to be the short wheelbase, bottom rung Six. The six-cylinder Hudson was by far the most chosen engine option for the 1942 Hudson’s, of which only 40,661 were produced.

Upon taking pictures of this car, it certainly prompted a few questions, such as for what time period were the blackout models built? This particular Hudson has all its trim pieces coated in chrome, something that did not carry through for the remainder of this truncated model year.

The “blackout models”, also sometimes referred to as “victory models”, were the cars built on and after January 1, 1942, such as this 1942 Plymouth. Instead of the bumpers and trim being chromed, these pieces were painted in an effort to conserve materials for the war effort. These blackout models are rather rare; automobile production in the United States ceased on February 5, 1942, so these models were built within a span of about five weeks. Further, the United States government had capped production for each manufacturer as well as commandeered somewhere between 500,000 and 540,000 of the 1942 model cars for government use and rationing. Any 1942 model car is quite rare, but the blackout models are even more rare.

The upside is that it’s easy to determine this Hudson was built during calendar year 1941, during the sunset of peacetime and automobile production prior to the horrors of World War II.

Perhaps there was some symbolism with my being pressed for time when finding a 1942 Hudson. When this Six was produced, Hudson was pressed for time to finish producing cars prior to their quick transition to war production. Further, Hudson itself was pressed for time as only a dozen years later it would merge with Nash to create American Motors.

This Hudson was for sale in the tiny town of Tipton, likely to entice people heading west to the state fairgrounds. Advertised as running great, our Hudson Six has an appearance that is teetering the border on the low end of the patina spectrum, a breath away from a less endearing descriptor. However if one were so inclined, it’s a great survivor that literally oozes with considerable and unique history.

She’s a solid old girl, and with a little love she could easily go another seventy-three years.

Nice with a grease and oil change plugs n points maybe a set of modern tyres and give the brakes a once over, I’d just drive it, if it hasnt rusted thru in 73 years its unlikely to in the time I have left.

We are restoring a 1942 super six. Not far to finish.

A great article about a great car. You brought out a couple of facts that I hadn’t read before… JL Hudson = Target, and the amazing built-in table!

The ad with “This is how you feel” is flatout weird. What’s the metaphor? Baggage cart? Rickshaw? Two-person wheelchair? Baby stroller?

Most people don’t want to feel passive when driving. Google is making the same mistake with their ‘autonomous’ car.

Prior to about the middle part of the 20th century, it seems as though any extraneous or strenuous effort was thought to be bad for the heart. I remember hearing my grandmother – born in the 1890s – telling her contemporaries, “Don’t strain yourself! You’ll give yourself a heart attack!” She’s probably turning in her grave, since I start my day with 30 minutes of high-intensity cardio exercise. 🙂

If you want to see something funny, watch the original HydraMatic promotion videos on YouTube. They make a fuss about how the automatic transmission saves a young woman driver from needless movements.

http://youtu.be/2xbgzNZWatE

Great find, excellent article, and nice opening paragraph. Also hoping some caring soul comes along and gives it a little TLC – not much, just enough to make it road-worthy…….

I LOVE this car. It’s a good thing it is so far away, or Mrs. JPC might be surprised to find her van parked outside, which would not be a good thing.

Though I have never had any personal contact with them, Hudsons have always fascinated me. I have especially been captivated by the 1940s models, from the speed-record-setting 40 model to the stepdown cars at the end of the decade.

The two things I had not realized were how long Hudson spent running on a near-empty tank, and that Hudson had a semi-automatic transmission. As a bit of an early automatic transmission geek, I am amazed that I had never even heard of the Hudson Drive-Master. Fantastic writeup on a fantastic find!

Good stuff, thanks. I never realized the connections to the Ford family and Target – I’ll make sure to bore my non-auto loving family with that detail the next time I have to drive them over there.

Hudson just moved up a notch in my estimation. They really fought the good fight and made what seems to be some pretty decent cars until the end.

I snapped this while out and about a couple of years ago. Not a great photo, but a Hudson for sale in a yard is a rare thing.

I’d ultimately love a Hornet but that is a nice little car.

I shouldn’t be all that surprised with the Hudson/Ford connection, the Ford’s married into the Firestone family too. I believe that current family scion William Clay Ford Jr. can claim both Ford and Firestone blood.

Or that Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, Thomas Edison & John Burroughs were good friends and took many camping trips together for years. They called themselves “The Four Vagabonds”. Kind of like African Safaris only in the US and motorized using cars and truck, most likely Fords.

Boy, what I wouldn’t give to go back in a time machine and listen to their campfire discussions!

For some reason, I fell in love with the advertisement you posted for the ’26 Super Six. Next weekend is the Old Car Festival in Dearborn. I see a perfect storm brewing! Now I’ll be casually looking around for a ’20s Hudson. 🙂

If anyone’s in the Ypsilanti/Ann Arbor area, I suggest visiting the Ypsilanti Automotive Heritage Museum. The proprietor is considered the last Hudson dealer in the world.

It also has Kaisers, Corvairs, and anything else that was built at the big Willow Run plant (other than a B-24, of course–it wouldn’t fit in their building).

http://ypsiautoheritage.org/

Thanks for the interesting writeup. After 73 years this car must have been on some great adventures with the many generations since. I hope it’s down time is nearing an end and the car will have another go around with a new family.

The history of Hudson and the other early makers of cars brings up a question. How could profits be made on such tiny production runs of such medium priced cars. Today there is so much platform sharing and worldwide sales and limited customer choices, yet look at how many choices Hudson offered in 41 with such limited resources and after many difficult years. Even with all the production efficiency of today, few automakers are immensely profitable. At some point, small production runs became untenable, I wish that could be overcome so that there could be a renaissance of choice before the driverless cars take over.

To begin with, developing an automobile was a lot cheaper back then. Part of the reason is that the companies were, for the most part, unfettered in what they could develop. There were no environmental regulations, crash standards, recalls, legal liabilities to the level they’ve developed over the last forty years.

A company was free to build whatever they wanted, at whatever level of quality they thought they could get away with and still receive customer acceptance.

Secondly, a lot of parts in those cars were used for decades. That Hudson six? I believe it was originally designed somewhere in the late 1920’s and was used thru the final (real) Hudson Hornets of 1954.

And before the war, while huge and dominant, the Big 3 weren’t as all encompassingly dominant as they became in the 1950’s. All the independents, grouped together admittedly, had a fairly good chance for survival if GM and Ford hadn’t gotten into that 1953 model year pissing match. That, more than anything else, spelled the doom of all the independents. And you’ll never convince me that that wasn’t the secondary intent of Ford’s push.

The first sign of how rough it was going to become was Kaiser, who after the first two years and the 1949 “Kaisers don’t retrench” error was obviously living on borrowed time. Hudson had foolishly overly-locked itself in to a body that couldn’t be restyled, and nobody expected GM to take styling in the direction that it went. Which, unfortunately, was at least 90 degrees off from what the independents had expected it to go.

The large Hudsons competed with Oldsmobile and the cheaper Buicks. Once the 1954 Buicks and Oldsmobiles appeared, with their wraparound windshields and sleeker bodies, Hudson didn’t stand a chance with a car that had debuted six years earlier. The lack of a modern OHV V-8 was another serious handicap for Hudson.

The independents largely competed in the medium-price field. By 1954, GM had that segment largely sewn up with Pontiac, Oldsmobile and Buick. The Chevrolet-Ford sales war didn’t help, but the independents simply couldn’t compete with the style, power and pizazz of Buick and Oldsmobile.

Packard didn’t compete directly with Ford or Chevrolet, but its sales hit the floor in 1954, too, primarily because it looked stale and lacked a modern V-8.

It still amazes me the degree of importance the consumer placed on having a V8 motor and automatic transmission back then. An equal displacement straight six is absolutely not inferior to a V8 in any way except in an all out race on a race track. If I was shopping for a car back in the late 40s or early 50s and I intended to do the maintenance myself, I would absolutely prefer a large straight six with a manual transmission.

So a Ford 300 Six vs. a 302?

Yes, indeed, the ’50’s Packard Clipper, which accounted for approximately 80% of their sales, competed directly with Olds and Buick. Both the latter received new bodies for ’54, increased engine size and horsepower and the re-introduction of the Buick Century. All this for cars having more features and content at lower or parity prices with Clippers.

People who sought the most car and relative prestige for their money immediately beat a path to the Olds and Buick dealers, realizing not only could they get a more modern car but also not suffer the terrible depreciation hit at trade-in time with a Clipper. ’54 Clipper sales tanked right at the time the company needed the revenue stream the worst.

As hard as it is to fathom now, the OHV V8 was simply all the rage in that era, considered the modern, coming thing. Any carmaker without one was at a terrible disadvantage in the sales race.

I get the impression that in 1950, if two versions of the same car were sold side by side for the same price and were the same except one had a 225 cubic inch flathead V8 with a 2speed auto and a single bbl carb…and the other had a 225 cubic inch inline six with overhead valves, a two barrel carb and a 4speed stickshift…the V8 version would outsell the inline six by two to one simply because is has a chrome V8 logo, two exhaust pipes, and an automatic transmission.

The flathead 6 was also used in the post-1954 badged-engineered “Hashes.”

Poor Hudson never stood a chance when GM and Ford got into a price war in the early 1950s.

To add insult to injury, Hudson had invested its limited development resources in the Jet, a relatively luxurious compact sedan that was priced significantly higher than a Chevy or Ford. Even 10 years later, when the Big Three introduced compacts, it would have struggled to compete. It took an additional 10 to 15 years and an energy crisis before the imports were able to successfully sell a compact at a premium price.

Great article!

Down here in Florida with the older cars, there’s people that have no problem driving a car with some rust on it, to show its full originality and yeah you have the perfectionists that never drive their old cars if there’s dust on it that day.

I recently also came across a ’42 Hudson in South Carolina, it’s a salvage log that sells complete cars from the 20’s up and like this Hudson most at that place are on the last call roster.

There’s four types of people that are driving by and looking at the Hudson that you saw; recyclers, snobs that think the only good car is a brand new car, tree huggers that will embrace the day when another old gas clunker is off the road and you the visionary, that knows you’re pressed for time to save this Hudson! Buy it!

I like it , clean lines and just enough bright work .

I can’t make out the price…..

-Nate

$3,750. It runs and drives well according to what I found advertised.

That might be sitting there for a while. It’s a little known car (except by car people) in questionable condition and it’s a four-door. Too bad. I hope the owner is realistic and open to offers that start with a one or a two in the thousands place.

Not to mention, “runs and drives well” could mean just about anything. You’d almost certainly have to dump the purchase price right back into it to get it reliable.

I found this in mid August and it was still there yesterday. You are right, the audience is slim and it needs love.

Wonder if the various Hudson clubs know about this one?

I like it in spite of the extra two doors , depending on the rust under neath and how well it actually drives (most think it anything old runs at all it ‘ drives great !! ‘) , I’d figure the value to top out around $2,500 as it’ll take a honest $45,000.00 to properly restore it….

This is one classic car you won’t ever have to worry about another , better one showing up at the Shine & Show .

Step down Hudsons tore up the NASCAR Tracks , look into what happened to them .

-Nate

I’m well-versed in Hudson NASCAR lore, but this is a pre-Step Down, pre- “Fabulous Hudson Hornet,” pre-Paul Newman in “Cars” car. Nothing wrong with a nice four-door, but the market will bear what it will.

This is probably not a car anyone would do a ground-up restoration on; that’s the beauty of the current “patina” trend. If you are socially conscious, you no longer need to be ashamed of driving a beater. If you are not socially conscious, it’s business as usual! 🙂

I’m still waiting for the loads of cheap ’30s and ’40s vehicles everybody keeps saying are going to materialize.

The cheap 30s and 40s vehicles were gone a by a few decades ago!

In 1977, my dad bought me my first car which is very similar to this one – a 1941 Chevrolet Special Deluxe 4-door, for $250. The seller was elated to be rid of it, and towed it all the way from the nearby town to our doorstep. I had it completely apart and sandblasted, with the front end sheet metal all straightened out, before I went off to college. The parts were sold off about 8 years later as I realized that I would never have the time to finish it.

Even back in the 1990s, nobody wanted 4-door cars. I couldn’t even give the body shell away so reluctantly I cut it up and hauled it off for scrap.

In 1973 I could have bought almost the same car, a 1947 Stylemaster for $125.00 from a friend of mine. It was all original and was in excellent condition inside and out with no rust. It needed new kingpins, I have been kicking myself for not buying it for the last 42 years.

My father had a friend back in the 40’s who owned a taxi company. Hudson was what he ran for cabs because “they would run for 200,000 miles without taking the heads off,” he used to brag. Also on blackout 42’s, even if old stock chrome parts were used, they had to be painted so noone had an unfair advantage over anyone else.

Interesting article about a brand I always liked. Happened to like both Hudson and Nash before they became AMC.

Additional note is that the brand has some claim on a “hot rod” legacy. When I was a boy the jalopies were a big favorite of mine and I followed one guy who ran a Ford V8 jalop. He hated it when another guy with a Hudson would show up. The engines were limited to 1948 or before. The big Hudson six was a winner that not too many drivers had. With twin H power it could not be touched but think that actually came later. Better than chevy or ford. Direct competitor to Olds starting with the Olds V8 in 49. I’ve always thought that Ford and Chev were good examples of wringing the last effort from an engine design with their small blocks. I think Hudson did just as well with their Flathead six.

This car tugs on my heart for some reason, four doors or not. I suppose one day I’ll pull the trigger on another old car when I have a cash surplus. I would do that if I saw this one. Or a Zephyr.

Folks: A must see museum for Hudon fans is Hostetler’s Hudson Auto Museum. See it at:

http://www.hostetlershudsons.com

It is located in the Amish area of northern Indiana. Well-worth a stop!

how did Chapin keep his glasses upright? there don’t appear to be any temple pieces….maybe old time auto execs sat very, very still? 🙂

Thats a Pince-Nez. It clamps to the nose.

Suitable for light office work only!

I’ve always wondered about those. I’d think they’d be uncomfortable.

Interesting car. The way the doors sort of ‘flow’ over the vestigial running boards give it a evolutionary missing link-feel. If it isn’t too rusty I could see paying $2 – 2.5K. I hope someone gives it a good home.

“…lifting their foot off the accelerator prompted the car to upshift to high.”

My grandfather bought one of those first Mercedes-Benz W120 Pontons with automatic gearboxes in the 1950s. The technology was much more primitive than the modern fully automatic gearbox. It required the motorists do the aforementioned procedure as to prompt the gearbox to upshift.

Eventually, he traded in for a 1962 W111 220 then 1968 W114 280, which had more modern automatic gearboxes and didn’t require that procedure.

The problem was the old muscle memory still stuck in my grandfather’s head even when driving his newer Mercedes-Benz cars. Riding with him was very much nauseating experience along with his prodigious use of cigars. He forbid us from cranking the windows down slightly for little bit of rejuvenating air because he didn’t want ash to be scattered all over the interior.

Hudson has always been an amorphous company to me, and this piece sets me straight. Love the archival stuff. Very crisp, very enjoyable writing.

Riding in an open car was fine in the good weather, but cold and miserable on inclement days and cold-weather seasons. Hudson gets credit for leading the way for the closed sedan body to dominance by the end of the 1920’s. In conjunction with Briggs Body Co., they developed the inexpensive-to-produce two door coach from straight cut wood frame and very few drawn metal stampings.

Initially the 1922 Essex coach priced at $1,245, the touring $1,045. By 1925, both styles were $765, the sales of closed cars took off. This move also forced other carmakers to develop closed models priced at or near parity with their open tourings and roadsters. The public quickly availed themselves of the more practical, comfortable option. Opens cars became the province of those after a sporting appearance and experience, approximate 10% of buyers.

If there’s no rust-through, that’ll make a great project for someone. Me, I’d leave the body as-is and save my work budget for the interior. Rare, and quite a good-looking design.

Hello, We are Good Fellaz Custom Classics. I was blown away reading this article because this EXACT CAR FROM TIPTON was just brought to us to restore for a man and his father. We would love some info and see if you would like to come see the progress.

http://www.goodfellazonline.com

http://www.alibipresentationstv.com

Good Fellaz

6164 Osage Beach Parkway

Osage Beach, MO 65065

573-693-1707

You have me curious. I’m guessing (hoping?) they are wanting it to be rehabilitated back to stock condition?

Email would work out fine and I can get with you that way if you prefer. Just leave a comment here to let me know.

I drove by your place just this past weekend.

That ’42 Plymouth is the first photo I’ve seen of a “black-out” trim car. I l also noticed that the ’42 Hudson only appears to have reflector lights on the back – were proper stop and indicator lights a mandated requirement back then?

Any idea where I could purchase a car just like the 1942 Hudson featured in the article? My parents had a two-toned version when the got married and unfortunately smashed it up on their honeymoon. They did get it repaired and drove it till the early fifties.

Awhile back I was perusing 1942 American car brochures to see if there was any sense of impending doom in the text or illustrations, or a more somber tone than usual that alluded to the darkening situation. To some extent there was – for example Packard’s ’42 brochure included this blurb: “This is a year for farsight buyers. It is a year when careful selection of a new motor car — with Quality guiding the choice — is bound to pay larger-than-usual returns… “. Hudson’s brochure included the page pictured below.

I also looked at some 1946 brochures to see how the first cars in almost four years were handled. Chevrolet’s included reassurances that the ’46 models were exactly the same as the prewar Chevys, which surprised me because I thought people would have expected some improvements after all the wartime technological innovations and be disappointed that there weren’t any. Was Chevy trying to spin that lack of progress to be a good thing, or was their real concern amongst consumers that postwar materials shortages (or something gone amiss in the retooling to car production) would cause quality/reliability problems?

The wording in the 1946 brochures was definitely just putting a very positive spin on the fact that Detroit was going to be selling nothing more than “same old, same old” for the 1946 model year. And this was due to a few reasons:

First off, car production only started again in the very late summer of 1945, and having spent the previous three years doing absolutely nothing but defense work, the Detroit automakers didn’t have time to do anything but un-tarp the old body dies and start pressing sheet metal again.

Secondly, they found out rather quickly that they didn’t have to do anything different. Customers were so desperate for new cars they they were willing to buy anything. While I don’t know my father’s discharge date (European theater), I do know that he was back at Motor Sales Corp. before New Year’s Day 1946 and selling Chevrolets again. Or, should I say, taking orders and putting people on the waiting list. There was no selling involved. He’d tell me stories of people who tried bribing him to get higher on the list. There was no way that Detroit was going to waste money bringing out a newer, better, car until they absolutely had to to remain competitive.

Third, given the aforementioned factors, of course Detroit took the cheapest ways out possible to get cars back on the showroom floor. There’s a reason why the ’42 DeSoto had those beautiful hidden headlamps, while the ’46 pretty much used Chrysler fenders modified to fit the DeSoto body – the ’42 was designed with the expectations that it had to stand out to sell against it’s competition in a normally competitive environment, the ’46 didn’t worry about competition. The only competition any of the manufacturers had that year was in having cars to sell. Period.

This really shows when you look at some of the things that were sold back in those years, products that no manufacturer in their right mind would have done five years later. Like the Crosley – the American desire for a kei car has always been tiny. Somehow you just know that 90% of those year’s Crosleys were sold to people who would have really rather had a Chevrolet, Ford, Plymouth or Studebaker Champion. But they couldn’t get one.

Or the knowledge that Kaiser and Frasier brought out lines of cars powered by a flathead six engine that was underpowered and barely sufficiently marketable back in 1940-42. But that’s all the more they could come up with for 1946 to get a car out, then made enough errors in subsequent years to ensure they never had the money to put a competitive engine in their cars. And even with a bit of an unofficial head start (1944-ish on design), the first real Kaisers and Fraziers were 1947 models. There were very few ’46’s built.

It takes time to design a new car. Even when you’re using a second-rate, easily available, drivetrain.

The other interesting point is that GM, Ford and Chrysler seemed to be smart to wait until 1949 to bring out their postwar cars. If you look at who brought out what as a totally new car when, every manufacturer that rushed to beat that 1949 model year ended up either out of business or definitely on the long slide to the end by the VJ day tenth anniversary. Now, a lot of that was due to the Big Three’s control of the market. They had the time to keep churning out old designs knowing customers would buy them until their new designs were well developed without rushing. The independents didn’t have that luxury. They felt they needed to get their new designs out first to try and capture as many sales as possible, hopefully to turn that into long term growth, before the Big Three came out swinging.

And, of course, GM set the standard. Every advanced design by an independent was made obsolete when GM didn’t follow ‘everybody’s expectations’ as to what a postwar car would look like. Tough luck, Studebaker, Packard, Hudson and Nash.

If you look at who brought out what as a totally new car when, every manufacturer that rushed to beat that 1949 model year ended up either out of business or definitely on the long slide to the end by the VJ day tenth anniversary. Now, a lot of that was due to the Big Three’s control of the market.

I think it came down to the Big Three’s control of the market. I doubt that the independents’ fate would have been any different if they’d introduced their postwar cars in 1949. Besides the Big Three’s control of the market, this is my take, manufacturer by manufacturer:

1. Kaiser-Frazer: undercapitalization, Henry Kaiser’s refusal to retrench.

2. Hudson: a unitized body that couldn’t readily be restyled, as you said. Sinking money into the Hudson Jet–but the cost of the Jet would have paid for a new full-size car or a new V8, but not both.

3. Studebaker: an antiquated plant, overly generous wages and dividends.

> Every advanced design by an independent was made obsolete when GM didn’t follow ‘everybody’s expectations’ as to what a postwar car would look like. Tough luck, Studebaker, Packard, Hudson and Nash.

Of those four, I think Studebaker came close to predicting the Big 3’s postwar style with their restyled 1947s. The ’52 model below is a minor facelift of the ’47 body, and looks not unlike what Chevy and Ford were selling the same year. Not so Nash, Hudson, and Packard, all of which bet big on streamlined upside down bathtubs.

All around, quality built. During my service station days, we got a Step-down in for lubrication. Just to see the underneath of one was quite a sight. Many lubrication points on these. I counted 33 “viscous chassis lubricant” points alone. One thing we didn’t do was renew the Hudsonite Clutch Compound. These cars had a very smooth, durable cork lined clutch that required this fluid.

Saw this one recently

I must have missed this nice writeup in 2015, Jason—-and I see the 2017 update of the car finding a home and restoration effort (I’d love to learn more!).

Right now I’m reading a big study of the U.S.’s industrial ramp-up for WWII, including the more alarmist pre-Pearl-Harbor, wanting to cut back on civilian “unessential” production earlier & more than others. Great to see today’s Hudson, which was part of that whole story…..