(Update: there’s a newer and more comprehensive article on a 1962 C80 truck with IFS here)

1960-1963 was a remarkable period of time when GM introduced a number of innovative vehicles, the result of an adventurous spirit in the air (or something in the water) at GM. The rear engine Corvair, the Buick aluminum V8 and cast-iron V6, the Tempest with its independent rear suspension and flex-drive, the turbocharged Olds Jetfire and Corvair Spyder. GM seemed determined to break out of its rather conservative mold on a number of fronts.

And the trucks were not spared either; in 1960, GM did something very unusual, even to this date: it equipped almost all of it s truck, from light duty pickups all the way to HD semi-tractors with torsion bar independent suspension. And like so many of the innovations from that period, this one didn’t last either; by 1963 solid axles were back, and the light duty trucks got a conventional coil-spring front suspension.

Presumably, that big-truck IFS was less than successful on several levels, because finding one still on the road has become nigh-near impossible. I actually did see one driving not long ago, but I couldn’t shoot it. So this handsome solid-axle ’66 Chevy C60 will have to stand in, and be a testament to the fact that not all innovations pan out.

The Chevrolet and GMC trucks were all-new in 1960, and were the first really substantial change since the Advance design trucks from 1948. The pickups and light duty trucks were significantly lower, due to an all-new frame that allowed the cab to sit lower, and new suspensions front and rear.

The rear suspensions on the ½ and ¾ ton light trucks had a new coil spring rear suspension. But the really big news was up front: a totally new SLA (short-long arm) independent front suspension with torsion bars. And all the way up to the heavy duty models (C80).

The frames for the light duty trucks shows how it drops down behind the front wheels, allowing for the lowest cab at the time. And the frame has a center X member, adding rigidity.

Only the 4WD and forward control models were spared the new IFS revolution. GM made a bold gamble with this, and like quite a few other of its bold moves during this period, it just didn’t pan out. No wonder GM became so conservative technically in the mid 60s and later.

Here’s some images I found at 6066gmc.guy.com of a C60 series truck’s suspension. I can’t find any conclusive information anymore as to why GM dropped the design after 1962, but I remember some anecdotal comments years ago about it being more maintenance intensive. And possibly not quite as rugged in difficult service conditions. And undoubtedly being more expensive. I suspect the last one was the over-arching reason it was dropped, as presumably there was no competitive sales advantage, and a higher associated cost.

What’s clear from these pictures is that the system for the larger trucks was not only much more rugged than the light-truck version, but the torsion bars act on the upper A-arm, whereas on the light trucks it works on the lower A-arm, like the Chrysler system. Undoubtedly this was done to keep the torsion bar out of the way of the undercarriage.

As a kid, I was surprised to not see the typical solid dropped front axle on some of these Chevy trucks, until I figured out what was going on. And they became rarer with time. So until I chase down that running C50 stake bed with IFS that I saw, we’ll have to move on for now and savor the solid axle of this C60.

And yes, it is a ’65, thanks to its tell-tale badge being in this position, and not down lower like the ’66.

And what is feeding those twin exhaust stacks? Sadly, I neither heard it running, or was willing to pop the hood as there were workers nearby from the company. But if it’s the original engine, we can make some guesses.

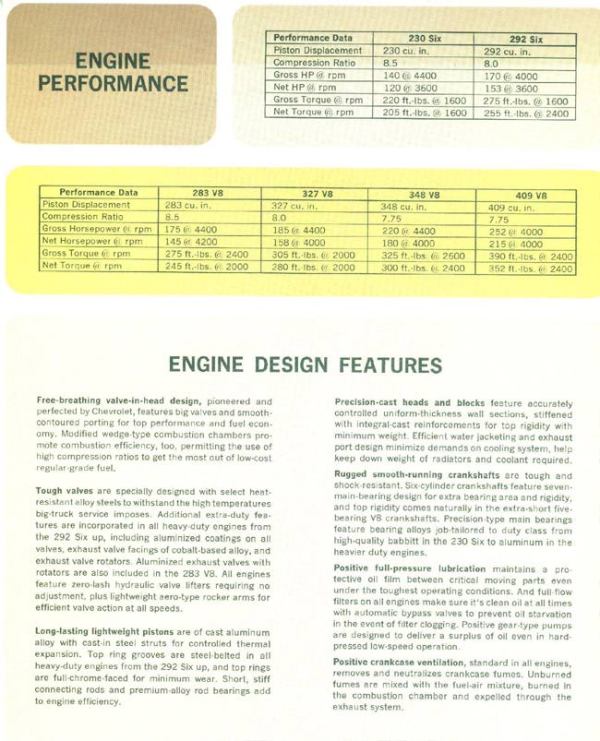

The standard engine for the Series 60 (15,000 to 21,000 lbs GVW) was the 292 six, rated at 170 gross and 153 net hp. Yes, truck engines back then were always shown with both gross and net hp, as the second number was the one that really counted. BTW, 153 net hp is pretty stout for an old-school in-line six with a one-barrel carb, more than a lot of V8s would muster in the 80s.

The optional engines (for the C60) 327 V8 with 185/158 hp, and the 348 with 220/180 hp. Note that the 292 had more net hp than the 283, and almost as much as the 327. That helps explain why it was commonly used in medium sized trucks; lots of torque and plenty of hp. And its torque came in at 1600 rpm, unlike the 283’s at 2400 rpm.

When I worked on a construction crew in Iowa in the early 70s, we had a C50 truck with the 283. Not surprisingly, for a truck engine the little 283 was a relative screamer, as it needed (and was happy to provide) lots of revs, unlike the Y-Block Fords in the other truck. Quite the contrast; but caning it to 5000 rpm for each shift did make me wonder how long it would last.

The 409 was reserved for the even bigger trucks (C80), but who knows, there could be any permutation of Chevrolet V8 under there now, even a 427, which made for a wicked-sounding truck engine at full chat. For that matter, nothing sounded better than the 348 and 409, with their distinctive exhaust bite.

Even if IFS didn’t pan out, we can still mull over the joys of Chevy V8 sounds through twin exhausts; even more memorable, and enduring. And here’s a question: has any other truck maker tried IFS in the heavier weight classes, other than Tatra?

(there’s a newer and more comprehensive article on 1962 C80 truck with IFS here)

I can imagine the torsion bar independent front suspension being used on Chevy/GMC light duty trucks, like the C10 and C20, maybe the C30. But for heavier duty trucks, it doesn’t look like something that would’ve worked very well, unless it was beefed up enough to withstand the heavier engine and drivetrain.

Great read !

In 2012 Volvo introduced IFS on its big FH-series trucks.

And for quite some time Ginaf has been using IFS on its 4×4 rally raid trucks.

Thanks, Johannes, for opening my eyes to a truck maker I’d never heard of before.

They’re heavily based on DAF technology (cabs, engines, axles), although the rally raid trucks have a

13 liter Cummins engine, tuned to 850 hp.

Below their biggest “standard” truck, as seen a lot here, both on- and off-road. It’s a 10×8 truck with hydropneumatic suspension, 4 of the 5 axles are steerable, and the (only) dead axle in the middle is also liftable.

Legal GVW 110,000 lbs. Factory guaranteed GVW ad another 22,000 lbs. As far as I know this is the only manufacturer that builds them with these specs. (I’m talking about trucks that are allowed to drive on any public road)

Great read. I always assumed the ’60-’62’s were coil springs like my ’65-’70 C10’s were. The way I used to thrash and off road my ’65, (went through a lot of junkyard lower control arms bottoming out after flying over dips on fire roads) smashing flat the underside of the arms, I can see the lower torsion spring would be smashed the same way hanging down so low. I got good at changing them quickly in auto shop so I could destroy them again the next weekend. I think similar hooning on this set up would create a lot more ground clearance and damage issues, possibly even collapsing.

Fascinating to see the differences GM used between the medium duty trucks vs light duty. I didn’t realize either one had torsion bars in those years, let alone the difference between where they connected to the control arms. It makes sense now, why I’ve seldom seen a ’60-’62 Chevy or GMC light truck that is raised. Most of the 1/2 tons at car shows from those years seem to always either be stock or lowered at the front for street. Makes total sense now given the poor ground clearance with low hanging torsion bars. . . Even with the added expense, I still wouldn’t mind having a ’60-’62 C50 or C60, with either a stake or dump bed. It would be a unique vehicle for hauling fallen trees and other large items. From a styling standpoint, I always loved the wraparound windshields and hoods with twin grille openings on the earlier models.

Interesting to note then the 348 V8 got a longer lifespan in medium-duty trucks, it was available until which model year for the C50/60/70?

1965

last year for 348,409 was 1965 in 60- 70 chevrolet truckss

Thanks for filling another hole in my knowledge.

I’m glad GM stuck with IFS on their light pickups; the C/10 was much better handling than ’60s Dodge D-series, which scared me a bit when I entered a curve faster than I should have. Well, one is not supposed to hot-dog these things, right?☺︎

My son had a similar experience in his old work truck (Nissan Patrol with way-overloaded utility box in the tray) when he somehow forgot he wasn’t in his Mitsubishi Lancer. Entered a roundabout at 60km/h…..

Somehow he kept it shiny side up, but he gave himself a BIG fright.

“even a 427, which made for a wicked-sounding truck engine at full chat.”

This is no joke. Even the Peanut Port Big Block Chebbies sounded great.

I worked as summer help at our Public Works Dept when I was a kid. They had 2 GMC dumps, one was a Tandem with a 427 (Tall Deck Truck block) and the other a Single with a 366 (Short Deck Tiny Bore Truck Block). They both sounded awesome pounding away at idle and rolling up to their 4k Redline.

I loved getting assigned to either one of those for the day. they were so much more fun than the geriatric Loadstar dumps that were on backup.

Big US Chevrolet and Ford gasoline trucks were very popular here in the pre- and post war years. But as the fifties went by, it was clear that the switch to diesel engines in trucks was irreversible. That meant that International and Mack -since they had their own diesel engines- survived the longest. Both also had their own Euro assembly facilities.

Note that I leave out the “domestic” (Big Three) Euro-trucks from the past decades. Like the Spanish Dodge trucks and the very successful Ford D-series from the UK, both cabovers.

I couldn’t find one photo of the above generation of Chevy trucks owned by a Dutch company, but this clean duo below will do just fine.

Interesting that on the light-truck version the torsion bar doesn’t align with the pivot of the bottom arm but just outside it.Haven’t seen that before.

The great thing with torsion bars on a car is that you can easily lower the suspension. The drawback is that the floor has to be above the torsion bar so it can’t be the lowest part of the car.

For a moment I thought I could help Paul out with a truck I saw last fall, but nope – this is a ’59, not a ’60. Still a great gnarly face.

Love the front end on this truck, especially the turn signals in the hood.

Great read. Love your coverage of trucks.

Very interesting dead end for a volume manufacturer. One question, specifically in relation to the view in the third image: How can the bar twist if the inner pivot of the lower control arm doesn’t coincide with the axis of the torsion bar? Even if the pivot axis and the bar converge to a single origin (the anchored end) I’d guess there’s a sheer action to be accommodated.

I hadn’t noticed that. It makes you wonder what Chrysler suspension engineers thought of GM’s effort.

I was wondering the same thing. How can the torsion bar twist when it’s not aligned with the pivot point for the lower control arm? Wouldn’t the torsion bar just break?

Apparently the torsion bar has to bend a wee bit too as well as twist, which shouldn’t be too hard on it given what’s it’s made of.

I really doubt they would design a torsion bar that also has to bend. Doing so would create stress concentrations at the ends of the torsion bar and a strong possibility of fatigue cracks.

I would hazard a guess that there is probably a swivel built into the ends of the torsion bar. I’m thinking a splined end that is not cylindrical shaped but slightly ball-ended.

Even with a swivel or slightly ball-ended torsion bar this is an inferior design to what Chrysler had. I can see why they got rid of it.

What are those lever like things highlighted with the bars on the anchored end? I have to imagine those are integral to making the system work. I wonder if GM was trying to get around existing patents with this layout, whatever the answer is it seems needlessly complicated.

Just the anchor for the non-moving end of the torsion bar. It’s attached to the frame. It didn’t really need to be highlighted, as it’s really just a frame extension.

I doubt there were any patents, as torsion bars had been used extensively for decades. It’s not really patentable.

I wonder if there is any advantage to which end the adjuster goes at? If I remember right, Chrysler started with the adjusters at the frame end, and then switched to putting them at the control arm end.

If nothing else, they do make it nice and easy to get the ride height just right.

They are lever arms on the ends of the torsion bars. They are more a part of the torsion bar than a part of the frame.

That is the adjuster for the ride height if you go full size with the picture you can make out the bolt that goes through the end of the lever to hold it to the frame. The torsion bar would pass through the adjuster into a bushing in the frame to locate it while the lever sets the “twist”. Without an adjuster you either end up with no preload or a really difficult to assemble system.

10/10! Great article Paul. Thanks for enlightening me on the subject.

I spent a summer as a teenager driving one of these old ifs C-60’s. Being the kid, I got the worst truck and this one was close to done. The steering had dangerous slop in it and the interior was bare metal. But the brakes were up to snuff and the 292 six ran great. It had a 2 speed rear end which I had to figure out. It was amazing how it would chug up roads just cleared by the Cat. I’d dump my load and go back. Often I had to back up hills to dump gravel, hardly my favourite.

I doubt it could go faster than 50 mph.

If you think about it, GM really elevated its engineers and stylists after the war. They got a brand new Technical Center, and their what’s next ideas on everything from cars to trains to kitchens were the highlight of the near-annual Motorama’s that ran from ’53 through ’61. There was a real push away from financial control of corporations to operational control – watch the movie Executive Suite for a demonstration, and Alfred Sloan’s retirement in the mid-fifties only reinforced that. The engineers would be in charge – until the bean counters lowered the boom, of course.

Good stuff. I owned a 60 GMC for several years, 305 V6. 8ft stepside 4 gear box. The torsion bar front end coupled with coil spring rears made for a fantastic riding truck. The V6 had great torque and a tremendous bark that would set off car alarms regularly. 10 mpg and the achillies heel, wimpy brakes. A friend currently owns a 60 Chev C60, still sporting its wheezy 235. No problems with the front end yet…

From what I understand, the torsion bar IFS was dropped on the larger trucks primarily due to cost and weight, but also possibly due to sagging issues. The upper control arm mounted torsion bars required the frame rails to be boxed quite a ways to the rear of the truck, and also needed a heavy crossmember or on some models an ‘X’ brace (shades of ’58 Impala!) to counteract the twist of the torsion bar anchor brackets. One odd feature of the larger (upper control arm) torsion bar setups was that they were non-adjustable, and if a sag developed there was no way to correct it other than replacing the bars. The light duty (bars on the lower control arms) were adjustable, and a slight sag could be easily corrected. GM uses torsion bar IFS on all their current HD pickups, both 4X2 and 4X4.

It’s also worth mentioning that the big Chevies were not the biggest IFS trucks produced by GM – those were the top of the range COE “Crackerboxes” like the one below, and if I am not mistaken, they also had an air suspension option.

Excellent ! It’s LHD, I wonder where a rig like that drove around. Maybe a “Michigan Special” ?

Front IFS air suspension was indeed featured on the DFR and DLR versions of the ‘Crackerbox’ from ’59-’62. The ‘Crackerbox’ continued with conventional leaf spring suspension until ’68. When the GMC R.T.S. II transit coach debuted in 1977, it had an independent IFS air suspension similar to the early ‘Crackerbox’ design.

There it is

Interesting. I have never really read much about the “crackerbox” GMCs, and had no idea that IFS was available on them. I used to see them on the road, and but never looked under their front end. I wonder how many were actually built with that IFS option?

I learned a lot from this one; never thought of torsion bars in connection with anyone by Chrysler. While Chevy/GMC seems to have gone quietly back to a more conventional setup for ’63, there was plenty of fanfare for the new ’60s–this teaser’s in all the papers (August 1959):

Packard used torsion bars in the 50s, front and back, for its famous self-leveling suspension. And of course Tatra and VW used them since the 30s. They were used in a lot of tanks in WW2 and such.

The Renault R5, known to usa consumers as “LeCar” was torsion bar suspension all 4 wheels. The front was using 2 longitudinal units, while the rear has 2 transverse units whichresults in a difference of 1.5″ wheel center to center measure from side to side.The rear torsion bars are as wide as the car so one sits ahead of the other. Other renaults of the era had torsion bars as well. I have a pair of these rides, and the charachteristics of the suspension, (very long travel, initially compliant with progressive stiffening) make it unique and enjoyable. I love unique engineering solutions, sad accountants have won out over engineers, now we have cookie cutter cartoon cars!

Yes; I didn’t mean to imply there weren’t others. And that distinctive off-set Renault rear suspension was first used on the R16.

You have two R5s? You should write them up for us some time.

Thanks Paul yes I realize, it just seemed many readers were not aware of how widely used torsion bars were, so i thought I’d toss the R5’s in the ring, I had 3 but had to sell my best due to the poor economy, it was a 1980 with only 23.000 miles! sigh!, but glad I still have my twins, ragroofs, 1980 and 1986, USA and Canada spec. respectively.

the 1986 is a daily driver, and hopefully the 1980 will soon be as well. I’d be happy to write them up, thanks for the invite. Ths is a really great site BTW, thanks.

Good; never heard from an R5 driver. Just the other day, Stephanie asked me if they made any with automatics, because she so loves how cute they are.

You can contact me via the Contact form for the specifics.

Yes, the R5 was made for the NA market with an automatic as far as I recall. My father bought one used in about 1980 and I recall that it was not the first one we saw because he insisted on a manual. It rusted quite badly quite quickly but compared to a late 70s Corolla it was not especially worse in that department. However, there were a lot more mechanical issues with it compared to our Toy.

Torsion bars were used in tanks long after WWII. In the 1980’s I was in an Army National Guard armor battalion and our M60A3 tanks had torsion bars, great big huge ones. This model tank was phased out of U.S. service around 2000 but it continues on in other militaries around the world. For all I know modern tanks have torsion bar suspensions to this day.

Kenworth developed a torsion bar rear suspension about this same time. I’ve heard it rode well, but was troublesome and wasn’t available long. Air ride was the coming thing.

Wheels of Time, the American Truck Historical Society magazine, just recently had an article on heavy duty IFS, some being still available on high end motor homes.

Alfa Romeo 430RE (1942 – 1950) – The greatest truck ever made

The B Model Macks might have something to say about that…

Not exactly the IFS system like in the article, but DAF’s H-drive system had both independent front- and rear suspension. Note that DAF only used it on military vehicles.

Below the YA126 4×4 truck.

DAF YA126 H-drive system. (Source: VTH9-326, Feb. 1959)

A very interesting read. Like several others, I was never aware of GM’s torsion bar trucks. I can see how a nonadjustable system for the HD models could have been sub optimal in the field.

I had a long wide box 1960 Chevy pickup for a while – I remember the slightly eerie ride it had in which the normal up-and-down movements were slower than expected.

We have a 62 3 ton that was in regular use on the farm until a few years ago. We still have it of course, because we keep everythin, but just today Dad was making noises about selling it. Weird. Anyway, it does have a very different ride from the solid axle trucks. Smoother I think, but tended to wallow somewhat when loaded. We also have a 63 1 ton, much different feel.

What an interesting idea for a big truck. If Volvo is trying it again today, maybe its time simply hadn’t come yet.

Also–the C60 pictured is one sharp-looking truck. The color scheme works but it’s also just a very nice-looking design!

the one advantage of the torsion bar suspension was an incredibly smooth ride … drove one for years in the 80s as a teenager … never did abuse it much, so can’t attest to durability under duress … I can attest to it being almost car-like as far as steering it down the road … much more comfortable than a straight axle … My family still owns the truck and my brother and I are pondering putting it back on the road just for fun …

I know it’s an old post but the most obvious disadvantage with the spring on the top arm is unsprung weight. Here in Oz the early Ford Falcons couldn’t outsell the Holdens until the first McPherson struct Commodores came out in 1978. Until Ford put a real front end under the EA Falcon in 1988, the fords suffered from more than twice the unsprung weight of a Holden or Valiant. Early Falcons, like 64 – 73 Mustangs had the coil on the top arm and over twice the unsprung weight of a “spring on lower arm” design.

Drive a 64 Nova and a 64 Chevelle down a corrugated dirt road and you’ll find out why. The “top springs” “pig-root” off the road sideways! GM tested the early Novas here against the EH Holden with the same result.

High unsprung will fatigue everything from the tyre to the driver.

There’s no difference in unsprung weight whether the spring is mounted on the upper or lower control arm. Please think about that for a minute. There’s no logic to your argument.

I had a 1961 Apache 20 put about 800# on it and rode like a Cadillac with those torsionbars under it but a 235 6? No power🤨🤔

Thank you very much Paul.

I always wondered why it doesn’t have springs. Now I Know!

With my dad we are repairing a 61, as soon as we finish it I promise to upload some photos.

In the 1980’s, I bought a broken-down ’62 Chevrolet C60 flatbed with a 235 to haul steel around Phoenix. I found a bellhousing out of a ’57 283, and installed a 292. It ran great,

BUT …

The front end was worn out. Once it got to about 40 mph, the steering would start a wild wobble that wouldn’t quit until you stopped. Think of going over railroad tracks in a ’62 VW Beetle with a bad steering damper. Back in those pre-internet days, I couldn’t even find new ball joints. So we fabricated mounts and installed a big steering damper. Problem fixed! (Or at least it was driveable.)

We ran it for another 5 or 6 years like that.

How do the cabs compare in size on a 1965 C10 and C60 ??

They’re all the same basic cab.

I have a 1960 chevy c60 27ft short ex Travis air force base wayne body bus with the front IFS. Drives Okay. Need front brake drums. Might try convert to discs.

We had a 1962 C60 on the farm for years. Rode nice and smooth. We had a bad ball joint about 20 years ago and We could only find a used one for $100 or so I think. We have since scrounged updated a few spare ball joints. Great truck. We swapped in a 235 6 out of a 1961 Chev car when the 261 died. Still parked in the weeds on our son’s place. It would probably fire up with a battery and some fresh gas.