(first posted 2/7/2016) 1965 was the last really big year for the big American car, and no car embodies that better than the 1965 Chevrolet. Never again would so many be sold: 1.67 million big Chevrolets; over a million Impalas alone. Never again would full size cars have such a large share of the market. Never again would there ever be a truly “all new” big American car like the ’65 Chevy; the genre had now evolved to a point where all subsequent versions were essentially refinements and variations. And never again would a full-sized American car be so stylistically ambitious, so stunningly beautiful, so radically different, and so be the near-universal love object of the land.

This is the peak moment of the big American car before its long decline, shot at sunset, appropriately enough. And in Evening Orchid, no less.

Part 1: The Ascendancy of Chevrolet

American automotive history, like so much history, can be boiled down to a few key eras, and the Chevrolet’s was arguably the longest and biggest of them all. Prior to the 1908 Ford Model T, cars were mostly very expensive and still largely experimental. Ford crystallized the state of the art in 1908, in a light but rugged utilitarian vehicle that lent itself to rural as well as urban use. By applying mass production techniques, he made it ever-more affordable, and the Model T became almost every American’s first car. But what about their second car? Would Americans be content to buy a black T forever?

Identifying that as the key vulnerability of Ford’s utilitarian vision—and acting on it strategically—was the genius of Alfred Sloan, GM’s President and the man who turned a loose collection of automobile companies snapped up by William Durant into an organized and highly profitable colossus. Sloan wasn’t the only industry leader who knew that there was no way to take on the Model T head-on on price alone. But he was the only one to develop and implement a viable alternative. It was based on the key assumption that once Americans had bought their first Model T strictly for utilitarian purposes, they would eventually succumb to the lure of style, and one that changed yearly. It worked brilliantly, for Chevrolet and for all of GM, as buyers would also be enticed to work their way up the ladder to GM’s higher-priced cars.

Throughout the 1920s, Chevrolet steadily worked to improve its quality, lower its pricing, and most of all, be attractive. The momentum that started a few years earlier really kicked in during 1926, when sales almost doubled to 548k. And then they exploded in 1927, when Chevrolet set two personal bests, selling over one million cars for the first time ever, and beating Ford in the process. Nobody else had come close to figuring out how to take on Henry’s Fortress T except for Chevrolet, which gradually worked its way up the siege ladder by offering a an ever-more stylish and comfortable car, without trying to match the T’s price head-on.

And with a few notable exceptions, Chevrolet became America’s number one selling car for decades to come, and the most profitable division within GM. Of Alfred Sloan’s many great accomplishments, none topped his success with Chevrolet. Except perhaps his decision to hire Harley Earl, in 1927, to create the first serious in-house design department, resulting in a stream of handsome cars like this 1936 Chevrolet. GM’s design leadership was only rarely challenged during the era that coincided with Chevrolet’s era at the top.

That manifested itself with Chevys that were consistently at or near the top in pleasing America’s eye, and with a string of design innovations, like the first hardtop in its class, the 1950 Bel Air. Style had been the Chevy’s key to success, and that would reach two new peaks, in 1955 and 1965.

The 1955 Chevrolet was all-new, and all-brilliant. It was trimmer and lighter than a comparable Ford or Plymouth, handled better, and most importantly of all, was bestowed with an exceptionally lively and efficient new V8 engine. And of course, it was a looker. The combination was unbeatable, and its dynamic qualities were respected even by the sports car crowd. The ’55 Chevy (and its ’56 – ’57 successors) became an instant classic, highly sought as used cars (and hot rods), and established the tradition of higher-than average resale prices for Chevys, one that would endure for quite some time and contribute to its enduring success.

In a banner year for the whole industry, Chevrolet sales surged to 1.704 million in 1955. That would be the all-time high for full-sized Chevrolets, but then there were no others, except for the Corvette, which managed all of 700 units that year.

Chevrolet made no bones about how it was marketing its all-new 1955s. It had gone from stealing the thunder of the Model T to the thunder of its own GM stablemates. The base list price of Chevy’s stylish new ’55 Nomad station wagon was higher than a Buick Century Riviera hardtop (not just a Special). But this wasn’t a sudden, drastic change; the “Sloanian Ladder” had been collapsing since the Great Depression. In 1930, a Cadillac cost about ten times more than a Chevrolet. By 1940, that premium was down to about 300%. By 1955, a Cadillac hardtop coupe cost about twice the Bel Air; less if the difference in equipment is factored in. And by 1971, the premium of a Cadillac Calais over a comparably-equipped Caprice was only some 10-25%.

The full-sized American car pricing (and differentiated bodies) scheme was collapsing. 1959 cemented that, when all of GM’s divisions shared the same basic body for the first time ever. But underneath the flamboyant wings and fighter-plane cockpits, the divisions still had the freedom to design their unique frames, suspensions and brakes along with their own drive trains. Except for the engines, that all would mostly end too, in 1965.

Of course there were a number of pragmatic reasons for that, as GM launched a wave of compacts and mid-sized cars beginning in 1960. By 1964, There were five distinct lines of Chevys to feed and nurture. That meant that resources once lavished only on the full-sized cars had to be divvied up.

The result was two-fold: Technical advances, bestowed so liberally on the Corvair, came to a virtual stand-still in the full-sized cars. Under their skins, a 1958 and 1964 Impala were essentially the same, riding on the same oft-maligned X-Frame and other chassis and drive train components. The only significant change was that the V8s were available with more displacement, and a new six cylinder, (necessary for the Chevy II), replaced the venerable Blue Flame six. The two-speed Powerglide, marginal drum brakes, slow and sloppy steering, and mushy handling were just as bad in 1964 as they were in 1958.

And while the big Chevy’s styling at least had some rapid-fire changes in 1958 and 1959, that all came to a virtual stand-still after a restyle in 1961. For four long years, styling changes were relegated to grille, rear end-treatments and side trim, along with one subtle re-skin in 1963. Not that it seemed to hurt any. And these 1961 – 1964 Chevrolets (clockwise, from top left), along with all of the earlier ones, long ago became the darlings of drag-racers, used car buyers, hot-rodders, hobbyists, collectors, low-riders, and more recently, donkers.

Their squeaky-clean all-American appeal led to higher resale values, which only further stoked America’s Impala diet. It was a bit rich on the empty calories, but who was going to argue with that in 1963? Consumer’s Report and maybe a few other serious journalists, who incessantly harped on the lack of handling, brakes, three-speed automatics, and a few other qualities that were clearly within GM’s technical grasp. But the bean-counters on the 14th floor were happy enough with the highly-profitable status quo. These cars were the big money makers, and as long as no one was complaining too loudly, why bother?

Full size Chevrolet sales had banner years during the X-Frame era. Unlike Ford, whose full-sized cars were clearly cannibalized by the new 1960 Falcon and 1962 Fairlane, full-sized Chevrolet sales held up just fine, even with the introduction of three new smaller lines; the 1960 Corvair, the 1962 Chevy II, and the 1964 Chevelle. In fact, one of the great unsung virtues of the Corvair was precisely that it brought in largely new buyers, unlike the Falcon. And the failed 1962 down-sized Plymouths weren’t really that much of a boost to Chevrolet; full-size Plymouth sales had already cratered in 1960; there was very little to scavenge from that carcass. In 1963, full-sized Chevrolets outsold Fords almost two-to-one. Chevrolet success during these years propelled GM to its all-time market share high in 1962 of 51%. That’s over half of the whole US market, not just among the Big Three.

Part 2: A New And Enduring Foundation

GM had milked the 1958 full-sized platform for seven very long years, which was an eternity back then. For 1965, all-new full-sized cars were on the program, and it would be the biggest change, technically as well as stylistically, since the tumultuous 1958-1959 years.

Let’s start with the foundation. GM’s 1965 B and C Body cars all rode on a new perimeter frame and a new coil-spring suspension. Before we get into the particulars, what’s really significant about this family of cars is that for the first time ever, all divisions shared the same frame and suspension. That was a clean break from the past, when the Fisher Body Division engineered basic common body shells (the C-Body was really just an extended B-Body since 1959), but the frames and suspensions were engineered by each division. In fact, during what I called the “X Frame Era” (full X-Frame history here), not all of the divisions used the X Frame (Olds never did), or only for some of the years. Only Chevrolet and Cadillac used it for the whole era.

In 1961, Oldsmobile and Pontiac started using a new type of frame design, (“perimeter frame”), with side frame rails that extended out to the very far side of the body, in order to allow a lower floor. That had been the original purpose of the X frame, but the perimeter frame had several advantages, including a perceived improvement in safety. In any case, it was clearly a better solution, and GM had several years to appreciate that with its use in the Olds and Pontiacs of the 1961-1964 period. Ford’s new 1965 perimeter frame was very similar to the Olds-Pontiac 1961 and the all-GM 1965 design. Full-sized American car frame and chassis design was now converging on what would become their final stage of development. The obvious exception was of course Chrysler’s unibody, which did sprout a front sub-frame in 1965, in an effort to improve its smoothness and quietness.

The configuration of the new 1965 perimeter frame was very similar to the one pioneered by Olds and Pontiac. And that basic design would underpin all GM BOF (Body-On-Frame) full and intermediate size cars right to the very end in 1996, and Ford’s similar BOF design to 2003. It was a mature technology, but also a dead-end.

The front suspension is a classic SLA (Short Arm-Long Arm) design, with geometry significantly improved from the previous generation, along with a wider track. The geometry induced more negative camber when cornering, improving control and stability. Brake dive was much reduced. Steering was also improved, especially the Saginaw power steering unit, now fully integrated into the steering box rather than the previous hydraulic booster. Overall steering ratio was 28.3:1 for manual, and 19.4:1 with power steering, which had 3.52 turns lock-to-lock (5.42 for the manual).

The rear suspension was also new and improved, with two primary trailing arms, carrying the coil springs. One additional upper control arm was used on the six cylinder and 283 V8 versions, and a second upper control arm with the 327 and larger V8 engines (and all wagons), to better control the motion forces under acceleration. The rear axle was a stronger Salisbury-type, and the driveshaft was now a one-piece unit.

The frame and suspension design on all of the new 1965 GM full-sized cars are all essentially the same, with only minor variations in details. This was another big step in the increasing centralization of the technical aspects of GM’s cars. That would soon also be the case with transmissions, as the new THM 400 and 350 were phased in. And that would of course eventually be the case with engines, as engine families used across divisions replaced unique units. As cars became more complex, with emission controls, complex HVAC units, safety requirements, etc., the old ways of engineering and building GM cars became increasingly obsolete. This was not just a cost-savings issue; changing conditions essentially demanded it. And the 1965s were the first big step in that direction, in terms of the full-sized cars (the new 1964 A-Body intermediates had already taken the same step one year earlier).

There was another aspect to this change in 1965: The Chevrolet was now closer than ever to a Cadillac under the skin, at least in terms of its chassis engineering and other aspects. And the remaining gap would only narrow over time, and eventually close completely. The new Caprice arrived in February of 1965 to compete against Ford’s LTD, with improved body rigidity, chassis tuning and a high trim interior not all that different from the Cadillac Calais. At the same time, the new 396 V8 and Turbo-Hydramatic 400 became available, and now the Chevy’s power train was its equal too.

The differences had been narrowing for some time, but this incremental creeping-up should not be underestimated. It is what eventually made the mid-market brands obsolete, a trend that has come to full fruition in recent years, with Ford and Chevrolet offering cars fully the equal of Lincoln and Cadillac, at least in certain models/trims. And that applies across the board with other brands too: The market has become drastically more compressed, and the rationale for premium brands has become more difficult to justify in terms of performance, interior trim, and other objective parameters. Increasingly, it’s the prestige value of the logo on the car. The Sloanian Ladder’s collapse was one rung at a time, and the 1965 GM full-sized GM cars were just one (big) rung less.

There was much that changed for the better under the skin; what about the parts that didn’t? The drum brakes were essentially carry-overs, 11″ in diameter with just under 200 square inches with the standard organic linings and 145 square inches with the optional sintered-iron lings. These optional linings resisted faded less and lasted longer, but had some shortcomings (noise, hard pedal when cold) that made them suitable mostly for hard-core performance drivers and heavy-duty use. The 1965 Corvette had standard four-wheel disc brakes; GM really should have offered at least front discs as optional (they finally did in 1967).

This applies to other aspects of the 1965 chassis: it had potential, but one that was still rather unfulfilled in its first few years. The shocks, although better positioned, were still not up to the task fully. And the tires were woefully under-sized, and not just because they didn’t begin to fill those huge wheel openings. The standard size for six cylinder and 283 V8 cars was 7.35 x 14, (which was essentially the same size as the previous year’s 7.00 x 14, thanks to some tire industry sleight of hand). 327 V8 and big-block cars received a bump to 7.75 x 14 (same as older 7.50 x 14) tires. These were all mounted on narrow 5″ wide wheels. At least wagons were bestowed with 8.25 x 14s mounted on 6″ rims. And all of these tires were of the controversial two-ply (four ply rating) construction, with weight capacity ratings that were precariously low compared to these cars’ size, weight and likely carrying potential, especially with the low 24 psi recommended pressure for that optimum Jet-Smooth ride. We’ve covered this issue before here.

Heavy-duty suspension and the F-40 “Suspension-special” as well as air-lift rear shocks were optional but were not widely promoted, and the take rate was low.

These chassis/tire limitations would soon improve steadily, as GM finally accepted the need to make their cars handle better and safer. 1965 was the year Ralph Nader’s seminal “Unsafe At Any Speed” came out, and it was a condemnation of the whole industry and its practices (the Corvair was just one chapter). There’s no doubt that the reason that Chevrolets started sprouting larger tires, on an almost annual basis, variable ratio power steering, optional rear anti-sway bars and standard disc brakes (1971). By 1970, although still on the same basic chassis and body, Chevrolets now had beefy 15″ wheels and tires, discs were standard on some models, and handling was improved.

Part 3: Mostly Nothing New Under The Hood

Under the hood, things looked all-too familiar too, which was not a bad thing, mostly, in terms of engines. The 1965s started with the exact same power trains as the ’64s, minus the 425 hp dual-quad 409. The two-speed Powerglide was the dominant choice, except for those still determined to do their own shifting. For those that took that seriously, at least the optional four speed was available with all engines except the six.

As of February 1965, the new 396 V8 replaced the 409, in two versions. The L35 was rated at 325 gross hp, and had a fairly mild hydraulic cam. It was available with the highly-regarded three-speed THM-400, which had debuted on 1964 Cadillacs and Buicks. The unit installed in Chevrolets did not have the “switch Pitch” variable torque converter stator, as used on some 1964 – 1967 Cadillacs, Buicks and Olds. But it teamed beautifully with the new 396, and finally gave Chevrolet a highly competitive power train (arguably the best) in its field. The 425 hp L78 version was an all-out high performance engine with an aggressive cam, mechanical lifters, aluminum intake, large Holley four barrel and other performance items, and was not available with either automatic.

Chevrolet, like all American car manufacturers, used SAE gross ratings for their engines until 1972, when net ratings were advertised. Engines were tested in conditions utterly unlike when they were actually installed in a car, including no air filter, fan, exhaust, generator/alternator, or other belt-driven devices, and the ignition was adjusted from factory specs to whatever maximum advance the engine would tolerate. Quite gross.

I’ve long wondered what the net hp of some of those old pre-emission-control engines actually was. Thanks to the GM Heritage Center, which has very detailed Vehicle Information Kits on line, here’s the net ratings for at least some of the 1965 engine line-up. Notably, the higher power V8s are missing their net ratings, probably because the gross ratings of these engines were commonly manipulated for competitive and/or insurance purposes. For instance, there is no real difference between the 425 hp L78 396 and the 425 hp L72 427 that was the top engine in 1966, except for the additional 31 cubic inches. That alone should bump up the 427 to 450 hp, or lower the 396 to 400 hp.

It’s probably a safe assumption that the 300hp 327 made some 250 net hp, and that the 396 made some 275 net hp.

Part 4 – The Driving Experience

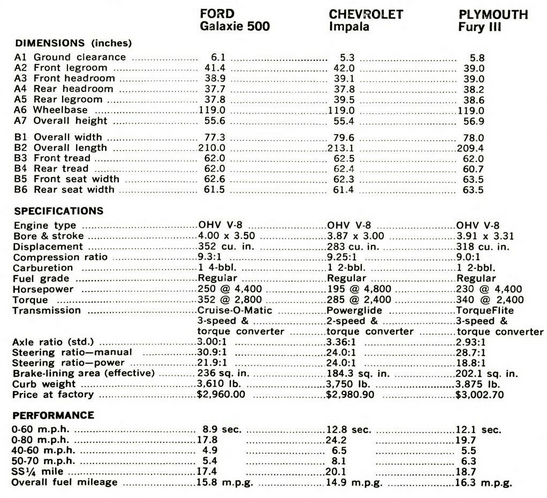

Needless to say, a 150 net hp 283 V8 and Powerglide equipped station wagon with a full load was pretty seriously taxed, never mind the 120 net hp 230 six. A 1965 Popular Science comparison (specs below) of the new Chevrolet, Ford and Plymouth pitted cars equipped a bit unevenly; the Ford had the optional 250hp 352 V8, the Plymouth the 230 hp 318 V8, and the Impala the 195 hp 283 V8. The Ford and Plymouth also had the advantage of three speed automatic transmissions. Given the Chevy’s disadvantages, it acquitted itself fairly well, performance-wise, especially against the Plymouth.

The Chevy’s lower fuel economy was undoubtedly the result of having to work more in its higher rev band to compensate for the lack of an intermediate gear, as the 283 was generally considered an efficient engine.

A comparison of these three cars by Motor Trend, with the Chevy and Plymouth equipped the same, but the Ford with a 390, yielded similar numbers, including 0-60 times of 12.4 for the Chevy and 11.6 for the Plymouth (9.6 for the 390 Ford).

Road Test wrung out a 300 hp 327 V8 PG Impala, and it did the 0-60 in 9 seconds. The 250 hp 327 was really the minimum for lively performance; which back then meant a 0-60 under 10 seconds. The 283 had been a great performer in the much lighter ’57 Chevy, but time, weight and increasing loads from power accessories had conspired against it. No wonder Chevy went to a standard 307 V8 in 1968, a 327 in 1969, and the 350 in 1970. And the THM 350 the “three-speed Powerglide”, arrived in 1969. It was all part of the rapid improvements this generation of Chevys received during its run. Too bad more of them weren’t on tap for the first year.

Car and Driver tested a 340 hp 409 PG Impala coupe, which ticked off the sprint to 60 in 8 seconds flat, and a 16.4/91 mph quarter mile run. In the spring of 1965, Motor Trend tested the new Caprice version with the new 325 hp 396 in a review we posted here, and the heavier four-door Caprice with the new THM-400 yielded an 8.9 second 0-60 and a 16.7/85 mph quarter mile. Of course, the 425 hp 396 would have left them all in the dust, but it was obviously not a choice for the average driver. (These vintage reviews will all be posted at CC shortly after this article)

And what about handling, and other dynamic qualities? All of the testers agreed that the new chassis was a significant improvement over its predecessor, and found the handling to be generally good, with much less brake dive, improved steering response, greater stability, and more controlled at speed. Overall chassis/body stiffness was improved, with less shaking and rattling over rough surfaces. That improved stiffness is of course essential to improved handling, but its potential was not yet fully exploited.

There were some demerits too, especially by Popular Science, which complained about (still) vague and lifeless power steering. But in comparisons to the competition, the Chevrolet was generally somewhat better handling than the Ford, which excelled at a quieter and softer ride, but not quite at the level of the Plymouth, which extracted greater control at the expense of a harsher ride. What one reads through the lines in all of these tests is that despite the improvements, these were not yet “great” cars, and handicapped by the (soft) standards and expectations of the times. Once GM applied itself on the subject, greatness was forthcoming. Not in 1965.

The brakes were a subject everyone danced around mostly, as they were marginally adequate for normal use, but everyone knew that these drum brakes were well past their sell-by date. GM dragged their feet in adopting disc brakes, let alone making them available, and it is one of their deadlier sins.

I’ve driven at least two ’65 Chevys; the experience was never really memorable, which is probably exactly what Chevrolet had in mind at the time. It was better all-round than its predecessors, but the improvements yet to come on this basic chassis would be welcome and overdue.

Let’s not beat about the bush: These all-new 1965 cars were hampered dynamically by penny-pinching, pure and simple. If they had been equipped as their 1969/1970 successors, with a larger standard V8, three-speed automatic, disc brakes and a bit more chassis tuning, their advanced styling would not have been hiding retrograde underpinnings.

Part 5: A Dramatic New Look

In researching this article, I was rather surprised at the lack of information readily available on the styling development and evolution of the 1965 Chevrolet and the other ’65 GM large cars. This was arguably their biggest stylistic change ever since the 1959s, for which there is abundant info and images. But there’s very little on the ’65s, and Collectible Automobile (“CA”) has never done a proper Design Analysis on these cars. What’s surprising about that is that these were the first culmination of the Bill Mitchell era, in terms of all-new full-sized cars.

Mitchell’s tenure as VP of Design at GM started in late 1958, but his influence didn’t come to full blossom until 1963, with the holy trinity of the Corvette Sting Ray, Buick Riviera and Pontiac Grand Prix. The two most important inspirations in his work, the muscular and point-nosed shark and the sheer look of a classic Hooper Rolls Royce, were now embodied in these instant classics. Everything that came out of Mitchell’s studios henceforth paid a tribute to these cars. It really was his peak moment.

CA has done two smaller articles on the ’65 Chevys, and that has yielded a few images along from other sources. The first one (above), supposedly from November 1962 (I have my doubts), shows a very conservative approach to a possible ’65 design, one that looks shockingly like a slightly warmed-over 1964 Buick LeSabre. There’s only a faint hint of the hips to come.

Here’s another, dated Nov. 5, 1962. This is certainly are more suggestive of what was to come, and the hips are now starting to show the form they would end up taking, especially on the lower one. But they’re still a smoothly-integrated, lacking the kick-up and the lower character line that distinguishes them from the final version. And there’s no suggestion of the semi-fastback roof yet. Or anything else that actually predicts the 1965’s design; in fact it rather predicts the smoother direction taken for ’69-’70 .

This clay, from the same date, does show a decided kick-up, rather close to the final version. But the front end is quite different, and the roof line is not very fast.

What happened?

I have heard references to a bold new semi-fastback design with the free-standing (although recessed, here) rear tail lights that was a bit radical but was adopted quite late in the game as the direction towards the production ’65s. The only image I can find is this one, which actually looks like it doesn’t have as “fast” of a roofline as the final version either. And the only reference to that process comes from “The Art And Colour Of General Motors”:

In the Chevrolet studios, excitement surrounded the big new Impala…a breathtaking departure from the angular 1961-1964 full sized cars. The responsibility that goes with designing the biggest-selling car in the industry didn’t deter the team, led by Irv Rybicki, from making a bold statement. Even though there was a load of “Chevrolet” brand character, from a wide horizontal grille to three-to-a-side rear lights, the 1965 was really avant-garde with a sexy rear-quarter “kick-up”, a “floating” knife-edge front bumper and tail lamps that sparkled like expensive jewelry on the gently curving decklid.

Everyone at Design Staff just knew this one was going to be a mega-hit, and it was….Funny thing, the ’65 Impala was a last-minute car. That flowing semi-fastback roofline, which ended up being shared by Pontiac, Oldsmobile and Buick, was a clandestine effort to replace the more Malibu-like roofline Mitchell had already approved.

Long after the 1965s were supposedly “locked in”, Irv Rybicki showed the semi-fastback proposal to Mitchell, who immediately fell in love with it. According to Dave Holls, “Mitchell needed GM president Jack Gordon’s approval for the last-minute styling changes.” recalled Holls: “Gordon arrived at design Staff, looked at both clay models, had no appreciation for anything he was seeing and said ‘Ah, Bill, it doesn’t matter. They both look about the same, don’t they?’ Mitchell was dumbfounded, blurting out: ‘The same? The same! That’s like saying Chicago and Paris look the same because they both have rivers running through them!'”

The stunning semi-fastback was approved for all divisions (except Cadillac) on that day, June 11, 1963.

Unfortunately, the name of the designer of that winning proposal was never given. But its quite a credit to him and the Chevrolet studio to be given the lead in designing the shape of GM’s new 1965 B-Body cars.

As to the origins of the freestanding round tail lights, here’s a sketch by Carl Renner, from October 6, 1957, a proposal for the 1960 Corvair. Like so many ideas floated all the time, it just needed the right project to be put to use on.

So let’s take closer look at what made the ’65 so special, stylistically. The front bladed bumper, which is raised and seems to float on the front end and allows the area below it to have “texture”, is a major deviation from the norm. Up to this time, bumpers were almost inevitably large, heavy and blunt, hanging across the lower portion of the front end. Never before on a mass-production American car had a bumper been freed from that position. It was a key turning point in the role that bumpers would play in the future of front end designs. Contrary to what might be expected, the front and rear bumpers were specifically designed to flex less when the vehicle was being jacked up by the bumper, as was the practice at the time.

The upper portion, with its protruding “forehead” leading edge just skimming the raised headlight surrounds, and the strong horizontal character line, are classic Bill Mitchell features, as seen on so many of the cars from his era, beginning with the 1963 Sting Ray and Riviera.

This dates back to perhaps Mitchell’s most influential design since his 1938 Cadillac Sixty Special, the 1959 Corvette Sting Ray racing car. On the Riviera, the leading edge was set back, between the two protruding fender blades/headlight covers. But in numerous variations, it became a signature of the GM look of the era, whether quite pointy as on the production Sting Ray, or decidedly blunt, as on a number of other GM designs.

The innovative front end design carried through to the hood, which did not continue through to the very front of the car, as was the near-universal practice at the time. It was “trapped”, and it created a serious challenge for the production engineers. But it played a key part in this leading-edge (literally) front end design.

One of the bolder choices made on the ’65 Impala was the absence of any bright accents on its long, flowing flanks, allowing the character lines and resultant shadows tell its story. This is especially the case with the Impala Super Sport, which even deleted the modest rocker trim of the Impala.

The Bel Air’s flanks were sullied by its bright horizontal trim. The only good thing to say about it is that it probably helped reduce parking lot dings.

I suppose this is perhaps the right moment to touch briefly on the 1966 refresh. Folks often have strong feelings about which of the two they prefer. Clearly, the ’66 is bit less adventuresome; the grille is squared up and less bold, the rear end also so, having lost the free-standing tail lights, and the bare flanks now have…chrome trim, even the Super Sport. That one detail alone makes the ’66 a bit retro-grade, in my eyes. If I had to guess, folks with more conservative tastes/outlook prefer the ’66, and those with a bit more adventuresome outlook prefer the ’65. Or maybe I’m just projecting.

The low-end Biscayne had a bright molding on the top of its hips, which was rather unfortunate. The poor designers; after they labor to come up with a new and successful design, they’re forced to dumb it down for the low trim lines. I vividly remember seeing a Biscayne in the showroom the night the ’65s were revealed at the Chevy dealer in Iowa City (an event seared in my memory), and running my hand over the Biscayne’s chromed hip, thinking Really?

We seem to have found ourselves at the Chevy’s tail, which is undoubtedly one of the bolder ones to ever grace the American roads. As much as I love them for their brashness, I will also admit to having some reservations about the taillights, inasmuch as they do look a wee bit like an afterthought, in terms of their relationship to the rest of the design. Which undoubtedly explains why they were a one-year wonder.

But I can’t imagine a world without them either. It’s as utterly distinctive, bold and instantly recognizable as any rear end design ever. Thank you, Bill Mitchell et al for having the guts to bring this to production.

Speaking of having stylistic guts, they were rather absent at the competition in 1965. Everyone’s large cars were new for 1965, and Ford and Plymouth both decided to chase the 1963 Pontiac’s design, which was a true game changer, and caused a mad rush to imitate it throughout the industry. The results, although not lacking in certain charms, were in a wholly different league than the Chevy. Both were designed almost exclusively with straight edges, and they failed to incorporate the ’63 Pontiac’s gently-flaring rear hips, a critical element and an obvious precursor to where GM was headed in 1965.

Admittedly, the more formal lines of the Ford, especially on the sedan, lent itself well to the new LTD and the ensuing direction it and the market were heading. One could argue that the ’65 Ford was something of a precursor to GM’s own downsized 1977 cars, by which time it was acknowledged that a more formal look was both easier to package in a smaller size and retain a certain “dignity”, as well being more in tune with the Great Brougham Epoch. The 1965 “sporty” Chevrolet was essentially the end of an era in more ways than one.

Ford scrambled to inject a bit of silicone in the ’66’s rear quarters, but Chrysler’s limited budgets meant it had to be put off until 1967. The flowing, rounded, fastback ’65 Chevys and their Pontiac, Buick and Olds B-Body stablemates had shown the way forward—at least for the moment—or was it sideways?

The ’65 GM cars’ bulging sides and curved side glass was really the fruition of What Virgil Exner had been working towards with his “fuselage” styling that first appeared on the 1960 Valiant, and would have been more fully realized with his 1962 proposals, as this “Super Sport” semi-fastback concept from July of 1959 makes quite clear. This is what the 1962 production Plymouth would have looked like, if not for the drastic down-sizing called for late in the development of the 1962 Plymouth and Dodge.

How much influence of that ’62 Super Sport concept are you seeing in the ’65 Super Sport? Exner’s hips stick out sideways; the Chevy’s straight up. Of course, there’s plenty of other differences, but in looking at the evolution of big American car design during their apogee, there’s no doubt that Exner’s designs were influential. His 1957s created a bit of a palace revolt in the GM Design Center, and his work on developing the fuselage look undoubtedly influenced GM too.

And of course, the ’65 GM cars would deeply influence the next new big Fords and Chryslers to come, which was in 1969. Both sported their take on the “fuselage look”, although the name would be commonly applied only to the Chryslers. GM actually pulled off a rather nasty little coup in 1969, as it sat pat on its big cars until 1971, except for another mild refresh, forcing Ford and Chrysler to spend vast sums on new tooling. GM obviously felt its 1965 bodies had enough mileage in them still.

The fuselage look reached its zenith in 1971, when the all-new GM full-sized cars pushed out their sides (and lengths) to excess, and in the process helped assure the decline of the full-sized American car and the ascendancy that mid-sized cars were already experiencing, starting in 1966 or so, culminating in utter domination of the sales charts by cars like the Olds Cutlass Supreme in the 70s and early 80s.

This trajectory towards morbid obesity came to a crashing halt in 1977, when GM downsized its large cars, to a size and format more like they had been back in 1955. They adopted a clean “sheer look” style that was a triumph of rationality as well as good looks, one which lasted for almost 15 years. It seemed like an eternity; only a design this good could have lasted this long. Farewell, Bill Mitchell.

But Americans are notorious binge dieters, and the swing back to ample roundness was probably inevitable. In 1991, the last generation of GM classic RWD cars arrived, with bodies once again pushed out on the sides, if not so much in length. Given that it still sat on the previous generation’s 116″ wheelbase, its proportions were not graceful from many angles, and it acquired the nickname “whale”. A mere humpback whale, compared to the 1971 – 1976 blue whales. Although these last Chevrolets of the breed had some high points dynamically, they were not a fitting ending stylistically, for a brand that had essentially invented the whole notion and succeeded on the strength of it.

Part 6 – Peak Success; Long Decline

And how did America react to the 1965 Chevrolet? It was love at first sight. 1.671 million big Chevys were sold, just slightly less than the all-time record in 1955, when there were only full-sized Chevrolets to be had.. More specifically, over one million Impala/Impala SS models were sold. The Impala SS, technically a separate model, had its best year it would ever have. And full-sized Chevrolets would account for a whopping 70% of all Chevrolet sales, a number that would decline steadily. By 1973, the peak all-time year for the whole Chevrolet brand, full-sized cars would account for only 26% of the total. What accounted for this?

Here’s the short answer. The new 1965 Mustang was an explosive hit, to the tune of 681,000 sold in its extended first year. The ’65 Impala coupe and ’65 Mustang were the two hot cars of 1965; one could not go wrong with either of them, in terms of social acceptance. But the world was changing rapidly, and not in the Impala coupe’s favor. While a young(ish) man, perhaps coming home from his stint in Vietnam or just having scored a steady job might well still be attracted to the Impala coupe in 1965, the demographic tidal wave underfoot (and the Mustang) would change that all very quickly.

And the Mustang was just one part of the equation. The huge success of the Pontiac GTO not only unleashed a raft of similar mid-sized performance cars, which also stimulated the whole mid-sized sector. One could rightfully say that GM’s move to consolidate their B-O-P compacts and the Chevelle on the new 1964 A-Body sowed the very seeds of the large car’s eventual demise.

The 1965 Impala was the last hurrah of the big sporty coupe. Yes, they were made for some time yet, but the bloom was soon off, and they quickly became “older men’s cars”. And it wasn’t just the coupes; sales of full-sized Chevrolets drooped a bit for 1966 (from 1.65 million to 1.5 million), but then the long decline set in. The years 1967, 1968 and 1969 saw sales drop into the 1.2 million range each of those years. 1970 sales plunged to 709k, in part due to a protracted strike. But sales never recovered much: 763k in 1971; 839k in 1972, and 977k in 1973, the big car’s last hurrah. In 1974, sales plunged again, due to the energy crisis, and stayed low through 1976.

The downsized 1977s managed an uptick to a respectable 662k, and sales were similar in ’78 and ’79. But after the second energy crisis, sales never recovered to even half that level, mostly bouncing around 200k, give or take, and then settling in for a terminal decline after 1991. And keep in mind that police, taxis and other fleets accounted for a very healthy percentage of those sales. The days of million-plus full sized Chevrolets being sold were quickly becoming a distant memory, as so much else from the golden 50s and 60s.

Part 7 – Vanessa’s 1965 Impala Super Sport

I have a list of historically significant cars that I want to find and write up, to tell the key chapters of automotive history. The ’65 Chevrolet has been on that list since day one, but I’d never found one on the street. In my mind, what I dreamed of finding was an Impala Super Sport coupe in Evening Orchid, and not a perfectly restored one either, but a genuine curbside classic. I long gave up on that hope, until a few months ago when I saw one just like that on the street, going the other way. Holy Bill Mitchell! The only ’65 I’ve ever seen on the streets, and there it goes, and I’m locked into traffic and can’t make one of my trademark U- turns in traffic and follow it. Ouch! But it gave me hope.

And then, walking through downtown with the dog on a rainy December day (weren’t they all?), there it is, parked in an office building lot. It was an awkward location for shooting, so I headed to the nearest office, walked in, and asked if anyone there owned the ’65 Chevy. “Oh yes! I’ll page Vanessa for you”.

Vanessa was ready for her afternoon break, and fired up the 327, which burbled happily but gently through the dual exhausts. After the choke was ready to back off a bit, she pulled out and across the street, to the curb.

The exhausts made their own fog to add to Eugene’s.

We lifted the hood, and found the compact small block nestled well back in the large engine compartment. At fast idle, its smoothness lived up to the 327’s rep as the sweet-spot of all the Chevy small blocks. It has of course more oomph than the 283, but it’s still quite short stroke of 3.25″ makes it smoother than a 350.

It was rebuilt not long ago, as the badge makes quite clear. The original decals were missing, so I’m not absolutely sure whether its a 300 hp or 250 hp version, and Vanessa didn’t know off hand, as the build sheet was in the glove box which was jammed shut. If the dual exhausts are original, it’s a 300 hp version. They’re essentially the same, except that the 300 hp version has a larger four-barrel carb and dual exhausts. Whether it really made as many more hp in net ratings as it was advertised will have to remain a dark secret. A safe assumption would be about 240-250 net hp.

But it doesn’t make a whole lot of difference; both versions were universally admired for their free-breathing and smooth-running characteristics, which made them quite capable of matching the performance of the larger 390 and 383 V8s often found in comparable big Fords and Mopars. Especially when backed by a four speed manual, to let the 327 really make the most of its rev-happy ways.

Vanessa invited me inside, where GM’s durable vinyl still looks great 50 years later, especially in white. Although they were called bucket seats, there wasn’t really any lateral support to keep one from sliding across their smooth surface when cornering briskly. And more regrettably, they seat backs had no adjustment. Yes, back in the day when all Americans watched the same tv shows, ate the same food and listened to the same music, they were all comfortable with one seat back angle. The good old days, when we were still told how to sit, by the nuns as well as by GM.

The trusty Powerglide’s shifter is on the console, along with the clock, since it had to give up its spot on the dash to a vacuum gauge. The optional tachometer replaced the vacuum gauge. Before any of you start wondering how it’s possible to have a semi-modern car with “only two gears”, please keep in mind that “the gears” are only part of the story of a torque converter automatic. Depending on the range of the torque converter, it’s quite capable of covering the effective range of several gears. A 327 Impala with the optional four speed and 3.31:1 rear axle ratio had overall gear ratios of 8.47, 6.32, 4.90, and 3.31, from first to fourth. With the PG, maximum starting ratio was 12.25, thanks to the wide-ratio torque converter, which made PG cars quite lively from a start. Low gear maxed out at a 5.83 ratio, and Drive at 3.31.

Top speed in Low depended on engine and axle ratio, but was typically about 55 mph with the 283 V8, 65-70 mph with the 327, and 75 mph with the 409. The biggest perceived shortcoming was of course an intermediate gear to bridge between Low and Drive, which would have made part-throttle downshifts at mid-range speeds less abrupt and not require the engine to rev so high. But the Chevy V8s were exceptionally willing to rev, and that quality made up some of the loss of the intermediate gear.

The Impala Super Sport came standard with the same 140 hp (120 net hp) 230 six as all the other models, but it did have full instrumentation standard to keep track of its vital signs, if you could see them, since a hand holding the steering wheel at the ten o’clock position conveniently obscured them. The vacuum gauge (or optional tachometer) was too far away for the driver to read; it was presumably on the far side of the radio to amuse the passenger. Or because the overall symmetry looked good to the stylists. As did all the bright surfaces that created plenty of glare. At least the optional tilt steering wheel at least offered some way of changing the driver’s position in relation to the wheel.

Isn’t that just splendid? And so inviting, as long as one is not too tall, as headroom under the sloping roof is somewhat limited. But who cared about that? Folks were happily squeezing themselves into the tiny rear seats of Mustangs; Americans were mostly still slim and limber. No wonder coupes have fallen out of favor; a lot of people nowadays would have a hard time getting in or out; the double cab pickup is America’s vehicle of choice for a good reason. Nobody in 1965 would have ever guessed that a Ford pickup would replace the Impala as America’s favorite passenger vehicle. No wonder these cars are held in such esteem; a reminder of just how much things have changed.

Vanessa told me a bit of how this car came to be in her possession, which is as classic of a story as the car. Her grandfather bought it new in March of 1965, in order to drive it to see her dad graduate from boot camp. An aunt then drove it through the eighties, and then was retired to a barn, until Vanessa’s dad got it from her in the early 2000s. After he passed away in March of 2004, Vanessa’s older brother stored the car for her until 2010.

Her brother got it in basic running order and it was shipped to Oregon. Since it’s been in Vanessa’s possession, the engine, transmission and the carburetor were rebuilt, and disc brakes replaced the drums on the front. Body work done to remove all of the rust from the upper half of the car and to eliminate leaks. The rubber seals around the windows were replaced, as well as the vinyl top. Another round of body work to get rid of some minor rust on the lower half of the car is next, before the interior gets fully refurbished, followed by an exterior paint job. Vanessa will keep it all original in appearance, including the Evening Orchid for the paint color. All of the work has been done at My Uncle’s Garage in Elmira.

Vanessa needed to get back to work, and drove the Chevy back to the parking lot, looking a bit out of place among the other modern small cars.

Especially so next to that Mini convertible.

It’s time to bid the 1965 Chevrolet and this sunny diversion back in time adieu, and continue our walk home in the drizzle of reality, steeped in the experience of the encounter and refreshed memories. Needless to say, this car’s arrival in the fall of 1964 made a deep impression on eleven year-old me. Never again would I be quite so excited about a big new American car. Apparently I wasn’t the only one.

7/3/19 Update: 1965 wasn’t really the peak year for big cars, in terms of market share. It was the last time they would sell in such large volumes, but the big American car’s market share had been falling since 1957. My post “Who Killed the Big American Car” puts all of that into proper perspective.

Thanks to George Neill and Don Andreina for vintage review scans and images

Related reading:

CC 1932 Chevrolet Confederate – Hark! What Rung On Yonder Ladder Cracks? J. Shafer

CC 1936 Chevrolet Master DeLuxe – Is It Too early For A Dubonnet? Paul N.

CC 1955 Chevrolet: The iCar – GM’s Greatest Hit Paul N.

GM’s X Frame – An X-Ray Look Paul N.

Powerglide: A GM Greatest Hit Or Deadly Sin? PN

CC 1958 Impala – A Ride To Remember J. Shafer

CC 1963 Impala SS 409 – Giddyup, Giddyup 409 Paul N.

Cohort Classic: 1965 Caprice – The LTD Reaction Paul N.

Undersized Tires: How GM Nickled and Dimed Americans (And Itself) To Death PN

CC 1966 Impala SS Convertible J. Shafer

CC 1970 Impala – The Best Big Car Of Its Time PN

CC 1972 Caprice Coupe – Cadillac carbon Copy? Tom Klockau

CC 1978 Caprice – GM Knocks One Out Of The Park Tom Klockau

CC 1985 Impala – Going Out In Style Jim Grey

CC 1990 Caprice Classic Brougham LS – Embarrassing FWD Cadillacs Since 1987 Tom Klockau

CC 1994 Caprice Classic LS – Last Of The Best Tom Klockau

A great article on a really special car! I was a senior in High school when these vehicles came out and the attention they drew was fantastic! I spent a lot of time looking through the sales brochures trying to figure out how I would equip one-never mind that there was no way I could afford one.

However,a friend of mine who had an after school job selling shoes somehow talked his mother into co-signing a loan for a ’65 Impala SS-300hp 327, 4 spd, positraction.. I remember him telling a group of us his mother told him if he missed a payment, she would be driving it. It was metallic grey, and he applied a black vinyl racing stripe down the hood, over the roof and on to the trunk. Racing stripes were really big then.

He ran the hell out of that thing-one day between classes he was crying the blues-he’d been playing road racer on the back roads and lost control; smashing up the driver’s side door pretty good. ” I had positraction and it didn’t help one bit” he lamented (well duh, positraction doesn’t overcome the laws of physics!) After graduation I only saw him one time-still driving the Impala. I think he got drafted…I never saw him again.

Brilliant, Paul – and a fantastic bookend to your 65 Continental piece, which I’ve used to explain the great income compression to my younger colleagues.

Also sent this to a client who has a pristine ’65 Super Sport h/t in black.

What really intrigues me is what’s left on your list of dream CCs…

Reviewing the article, I find there are a number of improvements that Chevy could have made to the 1966 models to address some of the deficiencies of the 1965’s particularly drivetrain and suspension.

A revised engine lineup with a larger standard V8 engine than the 283 cid plus a 2-barrel version of the 396 to compete against Ford’s similar 390 and Plymouth’s 383 – both of which could run on regular fuel:

ENGINES (Std.)

**Turbo-Thrift 250 Six-1 bbl.-155 horsepower (regular fuel). Transmissions ,3M overdrive, Powerglide.

Turbo-Fire 327 V8-2 bbl.-230 horsepower (regular fuel). Transmissions: 3M, OD, 4M, Powerglide, Turbo-Hydramatic.

ENGINES (Opt.)

Turbo-Jet 396 V8-2 bbl – 265 horsepower (regular fuel): Transmissions: ***3M, 4M, Turbo-Hydramatic.

Turbo-Jet 396 V8-4 bbl – 325 horsepower (premium fuel): Transmissions: ***3M, 4M, Turbo-Hydramatic.

Turbo-Jet 427 V8-4 bbl – 390 horsepower (premium fuel): Transmissions: ***3M, 4M, Turbo-Hydramatic.

Turbo-Jet 427 V8-4bbl – 425 horsepower (premium fuel): Transmissions: ***3M, 4M.

**Not available on station wagons, Caprice and Impala SS, and Impala Sport Sedan and convertible)

****Heavy-duty transmission.

Other changes for 1966 could (and should) have included: New 4-link rear coil suspension, Hurst shifter for 4-speed transmissions, optional front disc brakes or at least, finned aluminum drums similar to that used in Buicks, optional 15-inch wheels (standard on station wagons and with 427 V8) and beefier motor mounts such as the Safety Lock units introduced on the ’65 Pontiacs, and Turbo-Hydramatic transmission available with most V8s (including the standard) or at the very least, a Powerglide with “switch pitch” torque converter. Other suggestion: Leather seat options for Caprice and Impala SS coupes with Strato bucket seats and Strato bench seat in Caprice coupes and sedans, an all-vinyl version of the Caprice sedan interior for the station wagon, all-vinyl upholstery in several colors optional on Impala 4-door sedan, Sport Sedan and Sport Coupe (standard in convertibles and station wagons), and a Bel Air “custom decor group option” including front and rear padded seats in cloth-and-vinyl in sedans or all-vinyl in wagons plus full wheel covers, chrome door and windshield moldings, dual ashtrays front and rear; and trunk, underhood and glovebox lights. Some of these suggestions such as the front disc brakes did appear in 1967 while the 327 and 396 2-barrel engines, and Turbo-Hydramatic transmission with all V8s finally arrived in 1969.

Am I the only one who thinks it’s misleading to give names like “Turbo-Fire” to engines that are not turbocharged?

In a modern context, it is, but in 1965, the only production passenger car with a turbocharger was the 180hp Corvair Corsa, and I don’t think a lot of people who weren’t gearheads or pilots were that familiar with what a turbocharger was.

And add Cadillac’s new-for-1966 variable-ratio power steering thought it would likely be 1967 or 1968 before it would be extended to Chevrolet – that actually didn’t happen until 1969 on full-sized cars, Corvettes and Camaros; and 1970 for Chevelles, Novas and the new Monte Carlo.

If you look closely at the picture of the 1977 Caprice, you can see the front seatbelts being anchored to the roof of the car like they were on a 4 door hardtop of 1971-76 models. In production, the seat belts were anchored to the B-pillar.

Interesting catch!

Also, in the photo of the 1977(between the 1971 and

the Whale!), notice how car is angled downward toward

the rear – or nose up toward the front depending on

how you perceive it – a la Stude. I’m sure that did

a whole loada good for aerodynamics, esp at highway

speeds. 🙂

Thanks for the great article–glad I stumbled across it. I’m in the middle of a frame-off restoration of the 65 Impala convertible I’ve owned for 20 yrs now. It’s all original–Regal Red, 325/250HP. I’ve been struggling with upgrading the front drums to disc and the PG to THM-400 but after reading your article will keep it all original. It’s a piece of history and your article reminded me of that. Thanks!

I was 8 when these came out. South Louisiana loved Chevrolets and these were very popular, even in this color.

Just a few years ago, my wife gifted me with a set of DVDs of classic cars – old commercials, car shows, restos, customs, the works. One commercial was from Fall 1964 with the Bonanza and Bewitched cast (Chev was their sponsor at the time).

Ben Cartwright intros the bunch – Adam drives up in a Vette convertible and says a few words about it.

The Man from Uncle then shows off a couple of Corvairs, one a Corsa, demoing the telescoping steering wheel.

Samantha and Endora drop in and Sam twitches Hoss to the scene, then she nose-wiggles a new Chevelle with Original Darrin inside (the good one).

Hoss and Endora show off a Chevy II sedan.

Finally Little Joe gives a little spiel on the Impala coupe.

You can Youtube the video, however, my copy’s color quality is like-original whereas the Youtube is washed out.

I miss the old commercials where you actually learned something about the vehicles – good things to know, like how the F100 can isolate the driver from bursting light bulbs and how quiet the Fords are, assuming you could afford AC and not our usual 4/60 air conditioning.

Growing up in the New Orleans, LA area, I do recall many full sized Chevy 2 door “fastbacks”. Seems like SO many of them were: white exterior, blue bench seat vinyl interior, 283 V8 engines, 2 speed Powerglide transmissions, power steering and the excellent factory air conditioning (SO very desirable in this Hot & Humid area!)

However, it seemed like Ford and Mopar station wagons were more popular than a Chevy station wagon.

I am familiar with the ad in the comment by Dave B . Those things on the fenders

had me puzzled . I think that they are rear view mirrors that some dope

has put on BACKWARDS ! could this be? And isn’t this white interior spiffy

but keep the scrub brush handy

A 1955 Chevy handles better than the same year Ford or Mopar??????

1965 was the first year Chevies (and Buicks and Pontiacs and Olds) started with incurable (it seemed) rust around the windshield and rear windows. By 1968 a stroll thru a crowded parking lot here in New Orleans revealed GM cars with duct tape, butyl caulking, masking tape and other temporary stop gap means of TRYING to stop water leaking into the car’s interiors.

One of my favorite Chevy designs, and my utter favorite Chevy color: LOVES me some Evening Orchid!

My dad, who alternated between Chevys and Fords as company cars, ordered a yellow 66 Super sport . Yellow was popular, at least in California for a few years. Great looking car, but he turned in a 64 Galaxie 500 XL that we all agreed was a really good road car. It was equipped with heavy duty suspension and being from Ford’s “total performance” era seemed to benefit from Ford racing all over the world in all types of competition. Not just 1/4 mile and stock car. The Chevy was also equiped with HD springs and shocks but the the driving experience was not the same. We were building a cabin in the Sierra Nevada’s at the time and did much foothill and mountain driving on 2 lane winding roads. From then on I had little interest in cars that did not handle well which naturally led be to owning many foreign cars in my youth.

Excellent read!!! well done article!!! you should write a book about this. very well covered. you hit all the spots all the years……..nice job!!!

What an excellent article, I was a senior in high school when the ’65s came out and they were tremendously popular. My parents bought a ’65 Impala-4dr sedan, 6 cyl and powerglide like they they always bought. It may have been a great looking car, but the build quality-at least on this one-was terrible, it must have been built on a Monday or Friday; fit and finish of the exterior panels left a lot to be desired, the interior panels on the doors didn’t fit properly and it suffered from all sorts of squeaks and rattles. My parents drove it for about a year and a half and then traded it in on a 1966 Pontiac Catalina, the difference between the two cars was stunning, the Pontiac was a totally different vehicle and I mean that in a positive way. A 290 gross horsepower 389 and the turbo hydramatic made for a totally different driving experience. My parents never bought another Chevrolet after the ’65.

I didn’t have the time to go through all the comments. This is my most favorite car ad and still brings tears to my eyes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l02EGYwp2Go

This ad was knock out of the ballpark. You don’t have to be a Chevy fan but that is just an awesome ad.

Bob

Paul, this is one of my favourite CC articles authored by you. Nice concise history on the brand, excellent comparisons with other makes, how the styling was influenced, and some indication of your preference. What a great opportunity to meet with the current owner as well, what a great find!

I always preferred the cleaner styling of the 66 over the 65. The long rectangular taillights were just better than the round ones that looked better on the 64. I felt that the taillights on the 65 were artificially elevated somehow, perhaps unnecessarily, but certainly to the detriment of the styling. It made the ass end look uneven, perhaps even military to me.

Great piece!

Paul,

So as not to post a comment that is lengthier than your article, may I just say that, if somewhere in the world there is a university Department of American Automotive History, your exposition on the rise, peak and subsequent fall of the large American car could be the basis of a PhD dissertation in the discipline. Bravo!

Thanks. But in a way, this post is a bit misleading, as the big car’s market share started dropping rapidly in 1958. By 1965, it had already lost almost half its market share. I’m assuming you’ve seen my more recent post in the long decline of the big car?

https://www.curbsideclassic.com/automotive-histories/automotive-history-who-killed-the-big-american-car/

You are absolutely right about the writing on the wall for big cars starting in the late ’50s, but that takes nothing away from your insightful and concise analysis of the changes afoot, whose final results we are seeing today. I only wish the average new vehicle today weren’t a humongous pickup or a look-alike “cross-over, but wishing won’t make it so. Again, thanks for a wonderful tutorial on the long, declining road of the big ‘merican car.

Great article!

Superb article with many thanks for uplifting my day and love of these cars. Heres mine. Bought in Colorado and shipped by me to England. Best year and colour. Thanks to Mark for quality rebuild in Denver.

Hi Paul and Vanessa,

Thanks for your superb and educational story abut this legacy 1965 Impala SS.

I have a better understanding now of Bill Mitchell’s team design of my 65 Impala Convertible and 65 Impala Wagon.

Keeping this heirloom in the family is special!

Gary

Vanessa rocks.

I could swear the car in that November, 1962 sketch was a 1970 Torino.

Hmm. Bunkie…

Hi Bill,

Thanks for writing and posting this incredible article on the 1965 Chevrolets.

I agree that the 1965 Chevrolet is the pinnacle of Chevrolet styling and drive train performance.

I have a 1965 Impala Danube blue/medium blue convertible with the 230 I6/Powerglide and a 1965 Impala Medium blue/blue 9 passenger wagon with a 327/Turbo 400 drive train.

Thanks to your article, I have a better understanding of the design attributes of my special

1965 Impalas.

Best,

Gary