But back in London, Cosworth had hit a ‘stumbling block’ with the EAA engine. Mike Hall, Cosworth’s engineer responsible for the BD-series engines, commented, “It was extremely light compared to the BDA with its pressure die-cast aluminium block from Reynolds, but was not up to the ratings we were putting through it. Designed to be a two-litre racer, we could not make the cylinder block live. There was nothing we could do.”

Cosworth’s head of Sales, Jack Field, stated that, “Cosworth stopped development of the Cosworth Vega F2 – Sports Racing engine when GM wouldn’t update the block to keep it from coming apart. Experience with the engines confirmed the block was fragile. The top separated from the bottom. A crack would originate from the water pump opening and travel toward the rear of the block on the left side. The crack would either let the coolant out or worse let the oil out by cracking the main oil feed galley. The resultant oil spray would get on the headers and a fire would follow.”

Primarily used in Chevron B19, B21 and Lola T290 race cars during the 1972 and 1973 racing seasons, the engine’s light weight and power output made it a formidable competitor, with EAA-powered cars racking up a respectable number of wins and top-ten placements when the engine held together. But for the block’s weaknesses and other teething issues, it could well have pulled off DeLorean’s plan to dominate European F2 and SCCA “B” Production class racing.

A history of Cosworth Engineering written in 1988 recounts that, “Hundreds of blocks were being delivered, many failing a pressure test Cosworth devised for them and littering up the place while a solution was found. It never was. Those which passed the test were released, the first version stirring in anger in Guy Edwards’ Lola but failing to go the distance despite the attentions of Messrs. Duckworth and Scammell at Salzburgring.”

Accounts from EAA-powered drivers and crew indicated the engine would typically fail after 2–3 hours of racing. These engines were making 270 HP as previously mentioned. The consensus was that the stock block could handle up to around 250 HP when running longer duty cycles. GM did respond, belatedly, to the cracking problem by tooling up and manufacturing 50 units of an HD version of the block with extra ribbing.

But by 1973, Cosworth had had enough and pulled the plug – the EAA race engine project was dead. A number of the HD blocks subsequently found their way into hill climb, USAC Midget and IMSA RS Vega cars, and proved to be reliable and competitive engines in those applications.

Before we return to development of the street version of the Cosworth engine, it’s worth taking a moment to briefly touch on other engine options being considered for Vega in this timeframe. Per Ed Cole’s request, the Vega had been developed to accept a V8 engine, and a single prototype was built using an all-aluminum engine that was the last of several 283 cu in (4.6 L) units from the CERV I Corvette R&D program. Bored out to 302 cu in (4.9 L) and mated to a Turbo Hydramatic automatic with a stock differential and street tires, the car yielded quarter mile (~400 m) times under 14 seconds in Hot Rod magazine’s July 1972 road test of the prototype. That GM was seriously considering a V8 option is confirmed by the fact that early-production Vegas used transmission crossmembers with clearance reliefs for dual exhaust pipes.

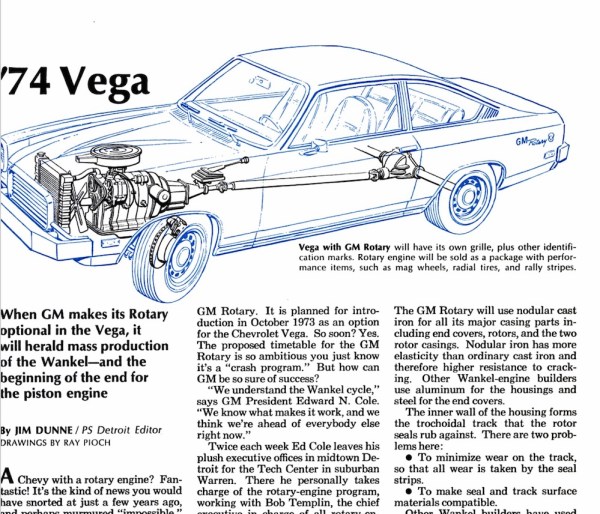

Additionally, GM had been busy working on its RC2-206 rotary engine, with intent to offer it in the 1974 Vega as documented in the May 1972 issue of Popular Science. In fact, GM had done durability testing of RC2-206 Wankels fitted in 1973 Vegas, but then decided to instead offer the rotary in the H-bodied Monza 2+2 – early-production Monzas had a wider transmission tunnel to accommodate the planned rotary. But it was not to be, as Ed Cole postponed the rotary program in September, 1974, retiring from GM the same month. Pete Estes, his successor, had little interest in the engine and the program was canceled in April, 1977 despite data from the R&D team indicating they felt they had solved its fuel economy and durability issues.

As an aside, development of the Monza started in 1971, well before Vega’s problems were widely known – Monza was not a response to Vega’s failures, but rather an attempt at a more upscale and exotic offering aimed at a market slot above the Vega.

Bill Mitchell couldn’t resist getting in on the act, either, with his ‘CorVega’ image car shown at the 1971 New York Auto Show. Originally powered by a turbocharged 2300 engine, the car was later completely revised with a Cosworth Twin Cam engine and distinctive bodywork.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t also mention the XP-898 concept from early 1973. While the body was completely original and made of innovative foam-filled molded plastic, all of the running gear was stock Vega. The one drivetrain exception was the engine, which used the stillborn cross-flow aluminum head that Chevrolet had developed. Power was better, NVH was reduced and the engine was a full 4” shorter than the stock Vega unit, allowing for a much lower hood line. Ah, well…

In early April, 1972, Ed Cole had test driven three Vegas including a stock base-trim car for reference, the prototype V8 car and a prototype Cosworth Twin Cam Vega fitted with dual Weber-Holley two-barrel carbs making 170 HP gross (about 130 HP net) and 125 lb-ft torque. He loved the Cosworth and offered his support for a run of 5,000 Twin Cam Vegas. Even Zora Arkus-Duntov was impressed with the Cosworth, stating it was ‘nicest 4-cylinder’ he had ever driven. DeLorean got his first ride a couple months later and signed off on development toward EPA certification and production. While two cars were prepared for 1973 emissions testing, they were never submitted as engineers were still working to sort part-throttle drivability and emissions issues. Further work was done on the cam profiles and to improve the torque curve, the cast iron exhaust manifold was swapped for a tubular stainless steel header to improve low-RPM drivability as noted above.

All this work delayed the program past the point where they could make the 1973 model year, so the new target release was 1974. Seven pilot build cars were assembled in April, 1973, all wearing silver paint and bearing COSWORTH VEGA 16 VALVE decals on their front fenders. Chevrolet Public Relations began teasing the upcoming limited-edition Cosworth Vega, with a formal announcement for the 1974 model year occurring in July of 1973. The car’s design had been frozen by this point, with the color scheme being revised by GM designer Jerry Palmer to black (a color unavailable on other Vega trims until 1976) with gold accents, bearing the COSWORTH TWIN CAM name on the fenders, engine cam cover, horn button, wheel center caps and on a plaque indicating the car’s build number fitted to the unique gold engine-turned dash panel. John DeLorean would not be around to oversee the final development of the car, however, having resigned from GM in April.

Enthusiastic reviews started to pour in from the trade rags, and in January, 1974, Car & Driver’s test of a Pilot build Cosworth Vega turned in the fastest 0-60 MPH time (7.7 seconds) of any car they tested that year (keep in mind, this was right at the beginning of the Malaise Era and the lightweight Cosworth was still making 170 HP gross at this point).

Finally it was time to run the car through the 1974 EPA test cycle. It’s an oft-repeated fact that two of the three test engines failed the test cycle. The backstory is that a decision was made (strenuously fought against by the Vega TC engine team) to significantly retard the timing in order to provide a margin of safety in the emissions results. This created excessive heat that caused failure of the exhaust valves and seats at around the 46,000 mile mark in the 50,000 mile test. The engine team was bitterly disappointed, feeling that the engine would easily have passed using the recommended timing settings.

The whole EPA test cycle, including months of durability tests, would have to start over from scratch – and would have to meet even tighter 1975 regulations. The Bendix electronic fuel injection system was revised to improve air distribution, and a Pulse Air system was added – this system did the same job as an A.I.R. pump, but without the pump’s 6 HP penalty (note that Pulse Air is different from an EGR system). High-energy ignition was added, and the timing was advanced, which, along with the requirement of lead-free fuel, ensured everything would work well with the now-mandatory catalytic converter. Internal Chevrolet testing required an engine be able to survive 200 hours at full load – the Cosworth engine went over 500 hours. Cal Wade even ran a test engine up to 9,400 RPM in a clutch burst test and the engine survived just fine (as did the clutch).

Three cars began durability tests in September, 1974 (the same month Ed Cole put the rotary engine program on hold and subsequently retired), each configured differently to ensure at least one would pass. Testing completed in January, 1975, and one of the three configurations met California’s tighter limits for 1975, so this configuration became the one used in production, making the Cosworth Vega the only GM car to be 50-State compliant. In fact, all three test cars came very close to meeting 1977 Federal standards.

In February 1975, five Pilot cars were built at the Lordstown plant. The first RPO Z09 production car was built on March 27, 1975 and on April 17, 1975, a media event was held at Lordstown, where the Cosworth Vega began rolling off the line at approximately 1.67 cars per hour on two shifts – two-and-a-half years after the original planned launch date.

A total of 5,000 Twin Cam engines were hand-assembled (and signed by the builder) in batches of 30 in a clean room at the Tonawanda, NY facility originally set up for assembly of all-aluminum ZL-1 427 cu in (7 liter) V8 engines. As an interesting historical aside, five low-mile used Cosworth Vega engines were purchased to use for reference by the Oldsmobile Quad 4 development team.

The Cosworth Vega was finally here, but reviews were not quite as gushing as they had been for the scrubbed 1974 model. Power was down to a mere 110 HP (net) at 5,600 RPM and 107 lb-ft torque; the compression ratio had dropped all the way down to 8.5:1. The 1975 Vega GT engine made 87 HP (net), so you got about 30% more power with the Cosworth, but that same Vega GT engine also made 14% more torque, at 122 lb-ft. The heavier 1975 Monza (called the ‘Italian Vega’ by DeLorean) launched with the same 2300 engine used in the Vega, but was also available with a 262 cu in (4.3 liter) V8, also making 110 HP (net), and if you lived in California, your V8 Monza came with a 350 cu in (5.7 liter) V8 making 125 HP (net).

110 HP may sound anemic, but power was down across the board throughout Chevrolet’s lineup due to 1975 emissions requirements. The L-48-powered Corvette (165 HP) was only slightly faster to 60 MPH, and a V8-powered Camaro (145 HP, but almost a half-ton heavier) took 10.9 seconds to achieve 60 MPH compared with the 8.7 seconds recorded by Car & Driver in a 1976 Cosworth Vega.

Where the Cosworth Vega positively excelled was in handling, partly because it received the revised rear suspension used in the heavier Monza. The Vega had always been a good handler if optioned right – Road & Track in 1973 reported, “With these tires (BR70-13) the Vega does better on the skidpad than every other car in our test summary except the Jaguar XJ6, very select company indeed. It also outdoes the ’73 Corvette on its radials in this particular test.” Reviews quickly racked up touting the Cosworth Vega’s agility: Car and Driver reported in October 1975, “As quick as the lil’ black Vega is in a straight line, it would be a big mistake to use one as a straight-line machine. The car’s forte is a nice, winding road. The sort of place you don’t see jacked-up Road Runners with drag slicks. This is where the Cosworth really shines. At moderate speeds, the car is as close to neutral handling as any American car I have ever driven … The outstanding feature of the Cosworth Vega is its excellent balance. Roll-stiffness distribution is ideal, with little understeer entering a turn, and just the right amount of drift from the tail as you put your foot down to exit.”

Road Test magazine’s October 1976 ‘Great Supercoupe Shootout’ pitted an Alfa Romeo Alfetta GT, Mazda Cosmo, Lancia Beta and Saab EMS against the Cosworth Vega and found that, “The Chevrolet Cosworth Vega is the only American car worthy of the lot. It is more than just some little super coupe … Read ‘em and weep, all you foreign-is-better nuts, because right there at the top, and by a long way at that, is the Cosworth Vega. It had the fastest 0-60 time, the fastest quarter-mile time, and tied with the Saab for the shortest braking distance … The Cosworth is American, and a collector’s item, and it came close, damn close to winning the whole thing.”

But despite the sparkling handling, and the fact it was the first American mass-produced automobile to feature a DOHC 4-valve, 4-cylinder engine, the first Chevrolet with electronic fuel injection and the first Chevrolet to use pressure-die-cast aluminum wheels, there were precious few takers. The price was certainly eye-watering; another $800 or so would put you in a Corvette, and Chevrolet even had the chutzpah to advertise the car as “One Vega for the Price of Two.”

Dealers were told to “play hard to get” – the thought being that having a Twin Cam in the showroom as bait would bring in customers that could be switched over to other Chevrolet offerings – these dealers often ended up sitting on cars long after they were canceled, eventually selling them at a loss. At least one dealer went so far as to fit Landau roofs on a few cars in hopes of finally moving them off.

After having moved only 2,061 units in 1975, changes were made in hopes of generating higher interest. Eight additional exterior colors were added, along with a number of additional interior color and material options. Along with the new grille and rear taillights that all 1976 Vegas received, the Cosworth got upgraded brakes, softer springs and a 1” higher ride height. An optional Borg-Warner T-50 ‘dogleg’ five-speed transmission paired with a 4.10 ratio differential was added and the 1975’s dual-outlet tailpipe was revised to a single outlet. 1976 sales were dismal none-the-less; only 1,447 units were sold (for a total of 3,508) before the plug was pulled for good. GM broke down 500 leftover Twin Cam engines for spares and destroyed the rest.

45 years later (as of this writing), the Cosworth Vega remains – aside from a small pocket of enthusiasts – an outlier in the collector market, despite being one of the rarest Chevrolet cars ever made. Many have of course succumbed to the ravages of time, hooning, accidents or V6 and V8 engine swaps. A variety of other engines have found their way under Cossie hoods including an Ecotec, a Mazda rotary and a 3.0 litre Cosworth V6. Non-runners may sell for a couple thousand or less, and a decent driver-quality car can be had for $6-8K. The current upper end of the market was set recently when 1976 Cosworth Vega #3037 sold on Bring A Trailer for $48,000 – this car had a mere 39 miles on both the odometer and the originally-fitted Goodyear BR70-13 tires. But there aren’t many Cossies left in that kind of time capsule condition…

I always wondered why we didn’t hear more about the Cosworth Vega – now I understand.

The photo of the Cosworth ‘factory’ is of the premises in Edmonton (near where I grew up) which they vacated in 1964 for a purpose-built factory in Northampton.

Excellent article Ed! This has to be the most comprehensive history of the Cosworth Vega I have ever read – well done. I also enjoyed the racing history. I recall you speaking of your old Vega, but I had no idea you had owned a Cosworth Vega. It looks like it was a very nice specimen and it certainly sounds like you enjoyed it thoroughly during your ownership. Bringing your car back to a stock appearance certainly improve the looks in my eyes.

It’s too bad the Cosworth Vega took so long to come to market and when it did, it wasn’t overly successful on the market. I often wonder how many people that were shopping for a small sporty European car would have seriously considered a Vega. Not only was it’s reputation poor by the mid-1970s but buying a Chevy Vega didn’t exactly have the same cachet as a BMW, Alpha or something similar. Its also too bad that the engineering and quality of the Vega didn’t match it’s good looks, road manners and in the case of the Cosworth the great engine.

Aaron Severson wrote up the Vega and Cosworth Vega over at Ate Up With Motor as well, which fleshes out the story even more.

Thank you, I didn’t know they had an article on the Cosworth Vega on Ate up With Motor. I will have to read it, I am sure its highly detailed.

https://ateupwithmotor.com/model-histories/chevrolet-vega-cosworth/

Probably the definitive piece on the Vega!

Wonderfully detailed and written article Ed. My memory is that the Cosworth Vega was always “right around the corner” and then delayed another year. The original concept was sound but the execution resulted in another “woulda, coulda, shoulda” for GM.

I’m glad that you got to experience it as it was meant to be. Great COAL!

A wonderfully detailed and written article Ed – thanks! My memory is that the Cosworth Vega was always “right around the corner” and then delayed for yet another year. It was another excellent concept but poor execution by GM, a “woulda, coulda, shoulda”. I’m glad that you got to experience it in the way that it meant to be driven.

A really excellent COAL!

Another dream that would never be, thanks once again to dad. Three years later I’ve also graduated with an M. Ed. and dad once again was willing to foot for a new car. Same restrictions: Must be a Chevrolet, and no Corvette (no out and out restrictions against a Camaro this time).

With the Cosworth-Vega available at this point, I didn’t argue the restrictions. And dad was interested (my Vega GT was still running well), until he saw the $6300.00 sticker. That killed it immediately, and I settled for a red Monza 2+2 with 5-speed. Which I really enjoyed although it wasn’t the autocrosser the Vega was.

This was the last free car. I paid for the next one, although dad managed to insert himself into the deal on that one, stopping me from getting what I wanted (so what if I’m paying for it, welcome to my family life) and sticking me with the worst POS I,ve ever owned. A 1979 Monza Kammback with V-6 and 5-speed.

I’ve read multiple comments you’ve written about your dad this week. I think the one on the Opel was from 2014 or thereabouts. Anyway, just to throw a little different perspective out there…it sounds like he bought you at least two new cars. Lots (most) kids get zero new cars.

Oh, I appreciated the new cars. It’s that there were always catches. It’s a family thing.

Thanks Ed for telling the whole Vega story. I was a bit sad that I never got to see this car in person, since I learned to drive in one and have a soft Vega shaped spot in my heart too.

Now that you’ve got this out of the way, I’ll be looking forward to the autocrossing report on your 40hp VW!

Great history, I have read everything I can find on the CV, and still learned a lot on this entry. The car was so, almost, the ’70’s Lotus Cortina. I have always been intrigued by the CV, and have imagined building the engine up in the way Cosworth intended, with big compression and proper carburetion. Unfortunately, I can’t get around the fact that doing the build would give me an engine that could reliably catastrophically crack the block at any moment, as Cosworth found out at the time. Lesser engine builds, such as the one the author owned, would fare much better. But the idea of owning a CV with a true 250+ horsepower is really the point of the thing. Waiting for the “Big Bang” every time I wound out the engine would sort of take the bloom off the rose.

It’s too bad GM was so aggressive at going after the best with Cosworth for its new Vega, while at the same time, pinching pennies at the moment of truth, when things were almost where they needed to be. Any person taking on an intensive build up of a race car or hot rod knows how the trade-off goes, how, at some point, one has to say “enough now, let’s wrap up this build”. But GM was right there, and from the looks of it, one modified/redesigned engine casting away from something for the automotive ages, rather than a fascinating footnote.

You might find the following comments of interest (lifted from h-body.org IIRC). Note the comment about a turbo’d engine making a reliable 300 HP!

A modified ’76 CV (making 260 HP) captured the Bonneville Land Speed G/Pro class record at 156.818 MPH in 2009. I believe that may have now been superseded, though.

Cosworth of England, when they ran in Group 2 sports cars, cracked or split blocks after 2-3 hours in enduro racing so it does depend on what duty cycle you plan on running. COE engines were making 270HP. I pit crewed for a Cosworth Vega midget owner in the middle 90’s. The stock block can handle around 250HP, above that it is suspect. The midget was running a HD block, GM made about 50 of these, and the owner experimented with lightening the crank. The crank was not balanced correctly and cracks formed above the mains. He then went to a stock block, the engine dyno’d at 300HP at 9000RPM, running 14:1CR on methanol. He made external re-inforcing aluminum plates that tied the top of the block to the bottom (I only have one picture of the right side of the engine with the plate, see below). The left side used three turn buckles plus a plate around the water pump. The stock blocks are a hit and miss, we have two CVOA members that have turbo’d the engine, both running boost over 20lbs, neither have had block problems. One a drag racer and the other a modified street car. The street car dyno’d close to 300HP at the wheels. These were all 2.0L sleeved engines.

Another discussion talked about making custom lower main caps that were wide enough for threaded rod to line up with the head bolt holes, thereby sandwiching the bottom end to the head. No one has put this design to test. When the blocks do split it’s at the water jacket (see other two photo’s below).

My autocross engine uses a long stroke crank and .070″ over bore, 12.7:1CR, 2.4L. It has run hundreds of autocrosses without any problems (with the exception of when it swallowed a bolt that mounted the air cleaner!) but the duty cycle is short. It makes between 230-240HP but it rarely gets over 7500RPM, the added torque from the longer stroke makes a whale of a difference.

Thanks! Good information. Early on, I was part of a pit crew for a group of guys who ran Vegas and CVs in IMSA RS and SCCA, back about 1980. Did a lot of work with both the stock Vega engine and the Cosworth version. One could simply look at a part and know which of the two it belonged to, by observing the quality of the casting, the machining, and the finish. The Cosworth parts really were finished to high end, tight tolerance, exact fit, with care in the finishing work and detail, right out of the box. The look and feel of the parts told one that this engine was something really special. The Vega parts were simply the typical banged-out pieces.

The problem with the Vega was the throwing of rods through the side of the block. The problem for the CV, even just a few years after production, was finding spare parts (basic engine reliability for the CV was not an issue for us). Though they share a common starting point, almost every piece of the CV engine is different than the Vega (to Cosworth’s and GM’s credit, they worked so hard to try to get it “right”). Racing programs often need spares that ordinary street cars wouldn’t generally need, an odd spare casting of some sort, say, or a flywheel. Not always available.

It’s frustrating to me that GM didn’t finally see it through, but I think the pollution control thing just sucked the power out of the street legal version, to the point where the engine people threw up their hands and said “that’s all we can do, folks”, with the pollution control and engine management technology they had at the time. On top of that, 1972 turned into 1975, the industry was deep into Malaise Mode, big-time racing faded a bit as a marketing tool, and time just got away from the CV program. With the end of the entire Vega production run getting in sight, the idea was to get what you have out there, instead of banging away on the last few issues. Since it would obviously be a 110 hp car in street form anyway (good, but not spectacular), there was no real customer for the car, at the price, other than those seeking something different and interesting. But at 6 grand, a hard sell.

I have always been intrigued by the CV, there is so much to it, and such a noble effort by a bunch of car guys at GM. The photocopied internal corporate pages in this article are tangible evidence of the car guys making their case to the bean counters, “we can make this work”. Of all of the GM efforts over the decades that didn’t hit their potential, this one could have been some cross of the original Shelby GT350 Mustang and the original Lotus Cortina. In the eyes of owners and some fans, it likely already is. Instead it is a secret car, nurtured by a secret society. You are either a member of that club, or likely don’t even know that it, and the car, even exist.

I will likely never own one, as I have reached the age and the point where I am finishing the projects I have rather than taking on new ones. But I came of age in the ’70s, and the CV was the next big thing, right around the corner, any day now…and then it wasn’t. Glad to see that a few people still carry the CV torch, as people do with the Yenko Stinger, for example, or the Lancia HF. Not everything needs to be a small block V8 or a Hemi. At any car event, I will likely beeline first to any CV in sight. They are such special cars, warts and all.

What a great history! I knew you had the Cossie, didn’t realize you sold it again though, thought it would be a forever keeper. But I’ve been through that myself last year so I get it. Still, as others have said, this is by far the best/most I’ve ever seen in one place detailing the car and you having owned one (and a standard one back in the day) brings an ever better perspective to it. I’m now trying to figure out what’s next for the man that I think went from RAM2500 to Diesel Beetle to Honda Fit to Chevy SS to Vega Cosworth. The SS must have half a million miles on it by now the way you drive it, but your choices are delightfully unpredictable.

Terrific article! I had a postcard of the CorVega that I kept for years, and now I finally know what the back end looks like – after over 30 years. (I could never find a picture online.)

The XP-898 looks a lot like the fourth-generation Camaro.

So for you, Mr Ed, it’s viva, lost Vegas?

A terrific article about a car whose NIH corporate gestation was so inward-looking that it amounted to strabismus.

Which might, perhaps, just account for their first twin cam.

Great information on a not very well known car.

I bet there are more than 500 still out there. I’ve come across 3. Two that were sitting in their owner’s garage, one of which had boxed and other junk stacked on top of its dusty body. The other was just dusty.

The third was one that came into the shop I worked at that was a certified emissions repair facility. As you noted the idle speed was 1200 rpm and the state emissions testing regime at the time required the idle speed to be 1100 rpm or less. When the owner went in for a test of course they told him that they couldn’t test it. He said but it is adjusted to factory specs. Eventually he was directed to the person with the state who was responsible for overseeing certified shops. He directed the owner to contact us as we had the highest level of cars actually passing their retest instead of issuing a repair wavier in his territory.

So late one day it showed up with the owner who brought along his factory shop manual. I stuck the probe up the tail pipe and gave it a sniff. It was within the CO and HC limits but of course idling at 1200 rpm. Tried as we did we couldn’t make it hold an idle at 1100 rpm or less. The supervisor showed up and then he fiddled with it for 45min before accepting that this engine would not idle below 1200 rpm. Not only would it die, the HC numbers were very high during the short periods it would idle.

So he signed the paper work so that the owner could license it, off it went never to be seen again.

Now he did say it was something he had recently purchased so I guess it is possible that it was one of the ones I’d seen in a garage. But I have to believe there are still a number of them sitting in someone’s garage, gathering dust and/or holding up boxes.

I would have been torn between a CV and a Mercury Capri with the Cologne V-6. The Capri would have been a better daily driver I think.

Terrific write-up on the CV! It just wasn’t in the cards, given the players. But it makes a great story.

And your car was the way it should have been, with some real beans in the engine. I’m glad you finally were able to fulfill your CV wish, with such a nice example.

I’m out here in the remote corners of Eastern Oregon, escaping from the smoky hell of the Willamette Valley. We have some surprisingly good cell coverage this morning, hence the rare comment from me.

What a great article! Brings back memories of me poring over the ’76 Vega brochure that I had as a 10 year old, wondering what the “Cosworth Vega” was all about. Best line that made me LOL, “The ’82 Cavalier that succeeded my ’71 Vega was a much nicer car by comparison.”

My God, I remember poring over the ’76 brochure at 10, and thinking how awesome the CV was!

Wow, what a great biography! Given your expertise on the Vega, you were the perfect author for this topic. In fact, another subtle clue yesterday besides your tail light photo, was most readers knew you were a Vega authority. I was thinking ‘Vega-related’ in seeing your writer byline before looking at the pic.

I apologize as I am writing on my lunch break, and I’ve yet to read your full article, but as a kid the Cosworth Vega engine and package seemed like a much better fit to me in the Monza. I know the Cosworth was well in development already, and you probably answered my question in your report. The Vega was slightly before my time, but as a kid then, the fresh Monza seemed like a better platform for the Cosworth engine and upgrades. I was young in ’75 and ’76, but knew the Vega already had a sullied reputation by then. And was old school compared to the Monza.

Like Ed Harsley up above, I can remember reading the car mags back then, and there seemed to be at least one line about the Cosworth Vega every single month for something like 3 or 4 years. Then it came out and the auto press went very silent on it almost immediately. Now I understand.

This is a story of the slowly morphing dysfunction that was GM at the time, and once DeLorean was gone from Chevrolet (and Cole from GM) the Cosworth’s champions were gone too.

I had not realized that the car had come and gone so quickly for you. But you have now checked it from your bucket list. If there a Vega Merit Badge you have earned it.

If there’s a Vega Merit Badge you have earned it.

Love it! Does a Vega key FOB count? (c:

(mine’s in a box somewhere right now, but looks similar to this one)

Great article, and I’m glad you had a good ownership experience. I have been rereading my old car magazine collection, and it really does seem like there is a Cosworth mention for every car produced. They covered it for years before it arrived, and then they mentioned it in every issue until GM stopped advertising it.

I think your tuned and tweaked Cosworth Vega was the way to go. The problem with the stock version was that it did too good of a job predicting the future. While it was very advanced in the mid-’70s, it had a mechanical spec sheet that was later matched by luminaries like the Toyota Echo. Collector cars are often valued for being obsolete in interesting ways, but the Cosworth Vega was exotic in a way that became mundane. The previous owner realizing the performance goals that were lost meeting emissions regulations made your car far more satisfying to drive. Also, even if stock rules in car collecting, there are still far too many ‘investment’ grade CVs running around for anyone to ever make any money on one.

Going off of memory, Ed Cole must have held quite a sway over GM. From being part of the development team for the ’49 Cadillac V-8, to overseeing the Chevy V-8 in ’55, he had to have been held in high regard.

But after “fathering” the the Corvair (and it’s adverse publicity) and then being allowed to follow it up with the the Vega, seems a lack of oversight on GM management.

I’m still wrapping my head around the T-50 transmission. There were so few units made for ’76, and the T-50 being optional, there couldn’t have been many Vegas so equipped. It seems that it was also available in (some?) H- X- and A-bodies, but it couldn’t handle much torque, so the largest engine to which GM mated it was the Oldsmobile 260 V-8.

I believe it was the first regular production option 5-speed in any American-made vehicle. I think I’ll do more research and see if I can turn the story of the T-50 into a post – there’s not much out there on the web.

There were several variants of the T-50 with different gearing. The unit used in the CV had a nasty habit of seizing up solid at speed due to a bushing being used where a roller bearing should have been, along with lightweight oil to help fuel economy. Current owners run heavier oil and overfill by 1 pint to alleviate this issue. When it happens, the whole drivetrain locks up, which makes for some interesting pirouettes.

My Brothers 1976 Pontiac Sunbird with 3.8 Liter Buick Engine had a T-50. He bought it used in 1979.Good for 38 MPG at 60 mph.

GM should have went for the stillborn L-10 engine with cross-flow aluminum head that put out 111 hp in the XP-898 concept instead of what was chosen for the Vega, perhaps it would have been an even starting starting point for the Cosworth Vega.

Would have loved to have seen the Cosworth Vega engine in the smaller Chevette as the US equivalent of performance Chevettes from Opel, Vauxhall and Isuzu.

Btw do anymore photos exist of the CorVega?

As configured for the 1971 show:

Another view of the Twin Cam version:

The stated reason was that the L-10 was not able to hit emissions targets. However, I’m sure Ed Cole (father of the Corvair) simply wanted the aluminum block and that was that.

I did a lot of mining of the old H-body.org forums in researching this article and found a number of comments from folks who worked at GM back in the day and had first-hand observations (at least from the perspective of whatever their role was). I’d like to eventually tackle another piece on the Vega’s development, as there are a number of so-called ‘facts’ that take on quite a different light when broader context is added.

Thanks for the images, rather like the look of the Black Corvega Twin-Cam.

One of the things that intrigues me about the Vega (from a non-US perspective) is how they could have been plausibly improved had the right decisions been made during development to remedy or completely butterfly away their infamous reputation, the same goes with the likes of the Pinto.

Another aspect would be whether there was a missed opportunity to commonise the Vega with the Opel Ascona A/B or a shortened GM V platform similar to what Vauxhall considered for the Cerian project before they were forced to turn the Ascona B into the mk1 Cavalier (and the Pinto with the mk3-mk5 Cortina) as was the case with the T-Car.

Was the displacement of the L-10 otherwise the same as the regular 2300 engine? Additionally was the 2300 conceived to displace just 2300cc or were other displacements envisaged beyond the 2-litre Cosworth Twin-Cam?

Also heard the CERV-based V8 used in the Vega V8 prototype was essentially an all-alloy Chevrolet Small Block V8, which together with the later development of the SB V8-based 90-degree V6 makes one wonder why GM felt the need to buy back the Buick V6 or attempt to buy back the rights of the 215 Buick / Rover V8 when they could have simply made their own 90-degree V6 from the Small Block V8 as well as produced all-alloy V6/V8 engines.

And drifting away from the Vega a minute, of the view GM could have also gotten away with developing turbocharged and dieselized Small Block-based variants in place of the Pontiac 301 Turbo and Oldsmobile Diesels.

There is no indication the 2300 block was ever intended to have alternate displacements. The Cosworth EAA was destroked to meet the 2 litre F2 requirement, easily done with a different crank. In fact, there are a number of street TC engines that have gone the other way – returning the engine back to 2.3 or even up to 2.4 litres.

While aluminum blocks (and heads) are commonplace today, back in this timeframe they were much more expensive than cast iron. Add to that the cost of development for a reliable street application that, more importantly and expensively, would meet ever-tightening emissions regulations, and it’s easy to see why the CERV engine never went beyond the R&D stage at that point in history. Recovering the Buick V6 was quicker, less expensive, and in hindsight, a brilliant move given how reliable and durable the engine turned out to be over the years.

What am trying to get at with the idea of GM developing an earlier Chevy V8-based V6 (instead of buying back the Buick V6) and producing all-alloy versions as was considered for the Vega V8 prototype, would be the fact that there was an opportunity for GM to apply the lessons they learned with aluminum on the CERV V8, 215 BOP V8 and L-10 prototype (in place of the 2300) engines onto the Small Block V8 and related V6.

That would have cost a lot more money than buying the unused Buick V-6 tooling back and bolting it right back in the exact same place it had been removed from.

Nice write up on the Cosworth Vega. My neighbor took the easy way out and dropped a small block into his Vega. Ran very well.

…this write up really makes me want a Cosworth Vega now. Excellent article dude!

Terrific writeup — and the soundtrack alone of your autocross video is enough to make me want to buy one!

Just got a chance to read this in full, excellent write up! I sort of knew the bullet points of the Cosworth but most information in between is very sparse, and the story is much more interesting than I imagined(I never knew there was an actual racing application for example. Or that it was used during the Quad 4 development).

It’s unfortunate timing, when you look at Japanese sport coupes in the 80s their specs weren’t far off from the Vega, 5-speed DOHC fuel injected 4 in a pretty capable RWD chassis? Sounds like a AE86!. The V8 Monza May have proved a better value and more conventional, but a V8 was a dead end in a sport subcompact car. Furthermore had it debuted when intended before the Vega image was tainted on what was the superior (IMO) original small bumper design, the idea of paying double for it might not have been quite as perplexing. Paying that much for an exotic engine in a car now well known as a lemon was a really bad proposition. Chevy would have been far better off putting that engine into the new Monza body than the tainted but also low end Vega body, but I understand why it’s own aforementioned complications nixed that notion for product planners(wild goose chase with the rotary engine).

By contrast the Taurus SHO had a rather similar background with its Yamaha V6, but unlike the Vega the Taurus had an excellent reputation to build off of despite it being introduced 4 years after the debut, and it didn’t cost double the price of a regular LX. It’s not some obscure footnote in Ford’s history as a consequence(it lasted 3 generations and the now extinct D3 Taurus actually revived it). GM had a real problem with their pricing structure starting about this time, not everything made in the 80s was bad or uninspired or out of touch with trends as it appears from the majority of examples (Buick’s T type trim being a major example that comes to mind) but they priced them out of being good values, the consequently slow sales nixed them from the line and buyers were only exposed to the laziest of GM engineering and image. When they were at the stage of the Cosworth’s final development, I just imagine someone asking “so how much should this package cost?” … “how about double?” …”yeah sounds fair. Now who wants some champagne?”, and that was that. No real number crunching, no marketplace analysis, and for the love of god don’t spend a dime of that potential profit on marketing (Hmm, Chevy SS, anyone?). The Cosworth Vega May just represent the exact moment corporate suits finally overtook the car guys in the company.

IIRC there was a dedicated machine that dealer service departments were supposed to use to diagnose and service the fuel injection system. I wonder how many dealerships actually got these machines and how much use they saw.

Ca. 1977 I struck up a conversation with a Cosworth Vega owner in Los Angeles. He said’ he’d replaced the fuel injection with a pair of Webers.

There were more Chevy dealers (~6,000, IIRC) than the planned 5,000 copies of the CV, so to get one to sell, a dealer had to agree to purchase the unique service tools and get training. Which I’m sure, in hindsight, they regretted. The service tools pop up for sale every once in a while – saw a set on ebay a while back that were still in their GM packaging.

Really enjoyed this piece, and find outing out about a car I knew little of, although was aware of.

Clearly, you enjoyed your return visit, and rightly so.

Thanks for the detailed feature Ed.

Brought back memories of my well optioned 74 GT which allowed me to travel many places including a six-week road trip through the US and Canada during the summer of 75. One stop on that trip was a Chevy dealership someplace in Florida which was displaying a Cosworth Vega. I recall its price tag was around the $6,000 and the car was a beauty. A salesperson was eager to help me cut a deal by taking my GT as a trade. Very tempting, but no.

Wow, missed this the first time around! I knew Ed was a fellow former Vega owner, but never knew about this Cosworth experience. So I need to retract the statement I made a few weeks ago about me being perhaps the only regular CC-er who ever drove a Cosworth Vega. Though I might still be the only one who drove a stock example. What was actually most interesting to me here was Ed’s experience with crawling back into a low, crude, harsh Vega after 40 years. I only had mine for about 3-1/2 years, late ‘76 to mid-‘80, but I took it on a multi-thousand mile road trip all over the West and carpooled with 2 or 3 other full sized males on a fairly long commute for about a year, once or twice a week. Sure, it was a bit cramped but I don’t recall any of that as a hardship, at least as long as I was in the driver’s seat. Automotive standards have really changed! And being younger didn’t hurt.

I must have been really busy in September to have missed this opus. I remember both the excitement before the Cosworth Vega’s release and the disappointment of the first road tests. Between the insane price and below expectations performance I can understand the poor sales. Personally, if I was in the market for a sporty rwd hatchback with black and gold paint in the mid 70s I would have bought a Capri. I think I would still favor the Capri as a more refined car, plus 7 year old me was fascinated by the rally car map light on the A pillar.

The Vega, both standard and Cosworth was such a missed opportunity, victim of GM’s hubris and parsimony, plus the general Detroit belief that small cars should be penalty boxes I would be very curios to explore the might have beens of a Vega with a Vauxhall 2300 slant 4 in standard and HSR form and a Mazda 13B swapped Vega. I want to like the cars because the early ones look like mini Camaros but they seem too flawed to be worth it to me.

The car was never intended to sell more than 5,000 per year. The mistake was the dealers didn’t sell the one they had when they had a buyer. Thats why only 2061 were sold in 1975 instead of 5,000. Dumb plan.They should have built 5,000 CARS in 75 and given each dealer one car. There were six thousand dealers then. Poor sales management. They only destroyed the 1000 engines cause 77 standard meant another test. You left that part out, and they wrote off each one for $10,000. that’s a million dollars. Maybe that was their plan from the start.

Wow, I never ran across the info on the writeoff of the engines, nor meeting the ’77 standards. Makes more sense in that light.

You should have had the valve stem seals replaced to cure the oil consumption. The block was never at fault. The seals would fall away with wear. I had it done on my 5 year old Vega GT for under $300. more than 40 cents a quart daily but I got 150,000 miles out of that engine without sleeves. Then the water pump failed and it overheated. I know someone with 400,000 miles on his original block. The silicon content is responsible for that. Dont overheat it and it will last longer than any cast iron block Period. End of story.

If we’d only known that back in the mid-late 1970s! I think I mentioned it, but the sleeved engine I put in my ’71 ran great and was quite reliable up through the time I swapped in the Buick 3.8l. We put the sleeved engine (back) into the ’73 Kammback it originally came out of, and my brother drove that for several more years.

I remember working at McLaren Engines inthe mid ’70s. My boss was Fritz Kahl (of Katech fame). He put the engine in a stock Vega (powder blue) and it ran fine till it lost oil pressure.! Now I know why??