This article started out rather differently than how it turned out. Finding GM Deadly Sins during the eighties is like shooting fish in a barrel; they’re everywhere; it’s much harder to find a GM car from that era that isn’t one. Of course, the Allante—which has somehow eluded our barrel so far—certainly qualifies; it was a classic dud during that era where just about everything GM churned out was deadly.

This should have been one of the easier Deadly Sins to write, but about a quarter of the way in, I realized I had gotten it all wrong. No; not about it being a DS and all of its obvious shortcomings. It was something rather different, and much deeper and more pernicious—GM’s cancer had been festering a lot longer before it made itself fully obvious.

Having made the wrong diagnosis, I had to start over.

My first take was the rather obvious one: GM’s decision to commission Pininfarina to design the Allante was the ultimate confirmation that GM Design had finally lost its way under the direction of Irv Rybicki.

Here’s what I had written: Can you imagine Bill Mitchell turning to Batista “Pinin” Farina in 1961 or so to ask if he might be available to design a Cadillac roadster—to be the ultimate image-bearer for Cadillac and GM—because he didn’t feel his staff was up to it?

Heresy!

But was Mitchell’s vaunted GM Design staff up to it? Once I started down the path of digging up examples of what his staff had created in terms of two-seater Cadillac concepts, my premise starting melting, like a clay left out in the rain.

So let’s go back in time and see how Harley Earl and Mitchell actually had envisioned two-seater roadsters and coupes for Cadillac, starting with this 1953 Le Mans. To the best of my knowledge—and limited research time—this is the first relevant Cadillac roadster concept, given that Earl had favored Buick as the brand for his milestone Y-Job and subsequent follow-ups in that realm. But by 1953, that all changed, as sports car fever was now a pandemic, and every division wanted to be a carrier.

Undoubtedly, the Le Mans name was chosen as a tribute to the success of Brigg Cunningham’s Cadillacs at that storied 24 hour race a couple of years earlier. But clearly, the Le Mans concept was more suited to boulevard cruising than a race track. It set the template for many subsequent Cadillac two-seaters: a way to preview upcoming styling trends a year or two before they were adopted by production cars, or to test new ideas for their viability. They likely weren’t actually feelers for a possible Cadillac two-seater, as that space was still being carved out by the new Corvette.

1954 brought the Cadillac El Camino.

Ans the La Espada, the open top version. They’re too big and ponderous, and with those Dagmars in front and big fins in back they look what they essentially were: shortened, cut-down Cadillacs, not a viable high-end roadster or coupe.

It’s clear that Cadillac was not taking the growing market for high end two-seaters seriously. This segment of the market was of course utterly dominated by imports, like this 1954 Ferrari 250 Coupe by Pininfarina.

More importantly, there was the 1954 Mercedes 300 SL, the first of the long line of cars that would come to define the heart of this market for decades to come. Cadillac utterly ignored that inconvenient truth, that the SL was the standard bearer for its brand, and as such a key element to its eventual success in toppling Cadillac’s hegemony in the US premium brand market.

Cadillac never tumbled to the fact that the 300SL was not just a cut down Mercedes sedan; it was a race-bred world-class sports car. That’s what made its reputation. It didn’t matter that subsequent SLs would be more like cut-down sedans than race cars; by that time its image was solidly established.

This key fact is precisely what all the premium sports cars from Europe based their success and brand image on: they were successful in racing, and established a genuine pedigree. This was something that couldn’t be faked, no matter how hard Cadillac might try.

At least Chevrolet got it, thanks to Zora Arkus-Duntov. Before he pushed to make the Corvette a genuinely competitive sports car, it languished and almost got cancelled. The 1953 Corvette suffered from that same cut-down-sedan image, with its standard Powerglide and six. That all changed, and very dramatically after the Corvette went racing and sprouted some genuine creds along with its vastly improved power train and chassis.

It’s not technically a Cadillac, but this 1955 La Salle concept shows how out of touch not only GM design was, but their engineering too. Its styling is provincial, at best; better suited to a carnival kiddie ride than something to even ponder putting up against the Europeans.

The fact that it was “FWD” without a functioning FWD drive train suggests that maybe GM did have the kiddie market in mind. It would have made a great pedal car.

And then there’s Harley Earl’s final blowout to the genre, the Cyclone XP-74. You like Dagmars? We got them; and then some.

Time to move on to the Bill Mitchell era, which I thought might yield some more promising concepts, renderings or models. It would seem rather obvious that the market for high-end two-passenger convertibles and coupes was growing steadily. The Corvette and its various concept offshoots was certainly getting a lot of attention by Bill, but what about Cadillac? Why not a high end roadster or coupe, to do battle against the “pagoda” SL as well as the various Maseratis, Ferraris, and such? Certainly they must have been pondering the growth of that market.

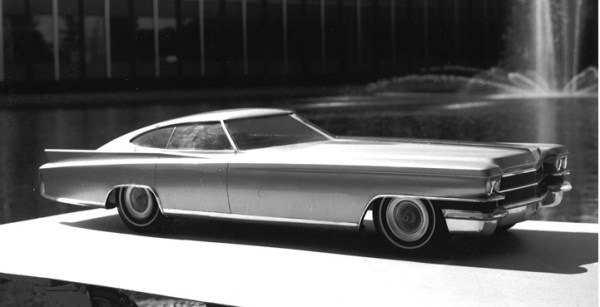

Here’s what my search for “two passenger Cadillac concepts 1960” turned up:

A two passenger coupe model from 1961. Pininfarina would undoubtedly approve. Such exquisite proportions!

This is apparently the first of a number of long nose concepts that came out of the Cadillac Studios in the sixties. And if I had to guess, it’s almost certainly the first of a long series of models and renderings created by Wayne Kady, who started his career at Cadillac in 1961, before moving on to Buick in the seventies. The recurring theme will be painfully obvious.

Ah yes; classic Kady, from 1963. I suppose this doesn’t really belong here since it appears to be a 2+2 or such, but it’s an insight into what was driving Cadillac styling in the sixties: Oblivious, to reality as well as the competition that was steadily eroding Cadillac’s image.

This one also from 1963 looks to be a two-seater, for what it’s worth.

Here’s another one, also attributed to Kady in 1963, has all the hallmarks of a roadster. Not a very realistic one, but then who cares? Cadillac was riding high in 1963, and who gave a damn what those guys in Italy or Germany are doing?

Actually, both Earl and Mitchell did, and they regularly traveled there and bought one or two of the best from the carrozzerias back to display in the lobby of the design Center, to stimulate their creative juices. Maybe Kady used the back door?

This one, also by Kady, got an official number, XP-840 (1965). Kady’s work invariably strikes me as if he were a sixth grader, who somehow got a job at GM Design and was told to just keep doodling away.

And his style, such as it was, continued to evolve, but only in the direction of ever-more outlandish.

It seems to have peaked in 1967, when this completely absurd V16 roadster rendering was made. Ah yes; now we’re really on a roll; something locomotive-sized with which to steam roll those pesky I-talians!

The Italians and other European designers did not indulge themselves in such outlandish child’s play. From the first sketch of a new car, it was always with the expectation that it was going to be built and functional as a car, even if it was a one-off.

My Google search for “Cadillac two-seat concepts 1970s” came up with nothing. Really? This was the decade of the Mercedes SL, when it steadily ingratiated itself with ever-more Americans looking for something with more style, image and panache than a…bloated 1975 Coupe De Ville. And if they couldn’t afford an SL, a 240D would do surprisingly well as an image-boosting alternative. Performance and doodads were not the criteria; the three-pointed star on the hood was the only one that really counted when you pulled up to the valet parking at the country club, restaurant, or in your driveway.

If you can find some evidence that Cadillac was taking this threat seriously in the seventies, in the form of concepts or renderings or such, I’d love to see it.

Meanwhile, others were stepping into the breach, resulting in a rash Seville roadsters. Even GM wouldn’t have done this, but one does wonder if the growing interest in these was noticed back in Detroit? Surely they couldn’t have not; they were too painfully unavoidable.

And then came the eighties, Cadillac’s—and GM’s—decade from hell.

Pages: 1 2

I’m going to start this on kind of an off note, but I honestly feel like Irv Rybicki and sons probably could’ve done a better job on this car than Pininfarina. I’ve always felt that the Allanté looked like a slightly squashed refrigerator box with oddly shaped door cutouts, and even if they wouldn’t have had hard points dictated by the platform GM put it on, the car still would have been lackluster. I guess I’ve never been a big fan of the “folded paper” school of design that many Italian cars of this era conformed to. I mean, it’s not heinously bad or anything, but it’s far from inspired.

Oddly enough, I do like some of the Rybicki era creations, save for the formal rear window treatment on some sedans (and coupes!). The N body spawning the 1986 Riviera-Toronado-Seville was bad juju, too. But I’m quite fond of the 1981-87 update on the 1973 trucks, which even hung in there nicely until 1991 on some models. The 1988 GMT 400 trucks were another stroke of genius, and the early W body coupes weren’t too shabby either. Though the 1982 A bodies looked too much alike, the Pontiac 6000 STE was a bright spot. It’s weird, as many of GM’s creations in this era were brick shaped devices, but they somehow look more pleasing to my eye. Admittedly, it did take me awhile to see the new Ford Taurus as a car instead of a moon rover, but that one truly rung in the 1990’s well ahead of GM and Chrysler.

On a side note, wasn’t that hunchback Seville and derivatives pushed through under Bill Mitchell?

That was an enjoyable read.

Comparing the SL and Allante profiles really drives home the point. The Caddy was so completely outclassed and outgunned.

I actually find more pinache in just the rear view of the Celebrity than the whole of the Allante.

When JR Ewing (of Dallas) started driving one of these, I think it symbolized the decline of Cadillac and the show, even though I was a teen and only a casual observer of both. But I really thought that at the time.

When Cadillac gave the 2-seat market a second shot with the XLR, it came closer to building a worthwhile competitor to the SL. The XLR was closer to what I imagined a Cadillac response to the SL should be, but even that was still a bit off.

I actually find more pinache in just the rear view of the Celebrity than the whole of the Allante.

Surprised to say I had the same thought. Here’s what I’ll say, the sheer look got overused but the Celebrity was probably the best execution of it since the 77 Impala(I never liked the 78 Malibu in sedan form much) and the biggest sin of the Irv Rybicki era at GM was it’s steadfast clinging to the sheer look, and the Alante in effect looks like Sheer look with the good aspects of it watered down.

Agree. Have also always thought that 1961 Jacqueline coupe is a real beauty.

Thank you for this deep dive into Cadillac’s troubled history with sports (and sporty) cars. This goes much deeper than my previous take on this car too – which was that GM was reaching back for the cachet of the 1959-60 Eldorado Brougham and its Italian bodywork and ultra high price, oblivious to the fact that Cadillac struggled in that price class even then.

Your treatment makes me think of how Cadillac was totally MIA during the 50s when everyone was mad for sports cars. Kaiser, Hudson, Nash, and of course the Corvette were among the attempts folks made. Chrysler’s Italian connection and the Dual Ghia were other more successful (if on a really low scale) high-end sports coupes. I had never really noticed how thoroughly Cadillac (at the peak of its influence) missed this boat. And if any manufacturer had the wherewithal to support a sporty coupe or roadster it was Cadillac.

As for Pininfarina, I am open to other opinions on this but I associate Italian design of the mid 1980s with a kind of industrial soullessness that seems appropriate for the Allante. Beauty is not the word that comes to mind when I think of the output from the Italian design houses in the 80s. But I guess it is relative, because their output was certainly leagues above what was coming from GM at the time.

I associate Italian design of the mid 1980s with a kind of industrial soullessness…

I can get this to some extent. Some of the overly angular designs don’t have an “it factor” for me. My favorite designs incorporate both straight edges and more organic-looking curves. The pendulum seems to swing back and forth, and my favorite designs tend to fall somewhere in the middle.

The looks of the Allante, though, is still within my pendulum-swing sweet spot. I still really like them, and not just because I was excited about these new, two-seat Cadillacs at an impressionable age.

My first thought about the photo of the 1955 La Salle concept was “Who sent over the circus giants for the PR shoot?” Looks like first she’s going to crush the windshield frame on the car, then she’s going to break the representative from the agency like a twig.

And those “long nose” concepts from the 60s?? It’d be hard to find anything more phallic in the automotive design world (although now I’m sure someone here will come up with something right quick). Not to mention all of the curbs, small animals, larger animals, and pedestrians such vehicles would eliminate just by the driver not being able to locate the forward end of his (no woman would be caught dead driving such things) vehicle.

I do like the 1954 El Camino, even if the Dagmars really only work because of the inclusion of the model in the photo shoot. Take her away, and the car’s Dagmars need to go too.

Excellent article and exploration. I enjoyed following your melting clay (much better than melting cake 😉 ).

Looking at the drawings, everything was stolen from everything else, along the way. One of the 1963 pieces has the later Toronado all over it.

As to the long nose treatment, perhaps the Jaguar E-Type was the driver for all of that. The Jaguar made a big design splash when it was introduced.

The Dickmobile was the absolute apogee of the phallic design.

I do like those white houses in the (those are duplexs or quadplexes I think, though they’re smaller than many modern single-address McMansions. Much more cleanly styled too, I’m guessing inside as well as out.

I’ve long found it odd the same era that gave us clean, no-nonsense housing and furnishings (now known as “mid-century modern”) also gave us the 1958 Buick. and 1959 Dodge.

The 1961 Jacqueline coupe makes me think of a 1962 Oldsmobile Jetfire that’s been entered in the Oakland Roadster Show, perhaps with the creative services of Chip Foose.

I think the Allante’s tops and windshield were too small for the rest of the car. You can’t look rich and powerful when your accommodations look like an afterthought.

I believe that the forlorn looking Allante parked next to the Celebrity has tires that are considerably smaller in diameter than the 225/60R15s that it would have been delivered on. Were the originals smaller than they should have been? Sure. As production went along, the originally specified 15 inch wheels and tires were replaced by 16 inch wheels with 225/60R16 tires. How often to you see a plus one size that doesn’t involve an appropriate reduction in sidewall height to remain overall diameter?

I don’t know that the styling mattered. It mattered that a big chunk of what one paid for an Allante was for a trip to Europe that the buyer didn’t get to go on. It mattered that GM launched an expensive car with a tainted engine. It mattered that GM finally upgraded the car’s performance in the final model year, only to kill the project. It mattered that when GM replaced the feeble HT engines with the powerful Northstar, they got it so wrong that it took many years to build one that wasn’t a time bomb. I consider the Allante styling to be far more attractive than that of the Buick Reatta, but at least the Reatta had a drivetrain likely to last as long as all the other components of the car. The only way to win the GM car game is not to play.

Interesting you mentioned the Jacqueline Coupe – it instantly reminded me of a 1960s era Nissan Cedric. Which isn’t a coincidence, because Nissan had also used Pininfarina for some of their designs for the Cedric during that time.

The Sloan structure comes into play as well with the Corvette, despite being a Chevrolet in division and powerplants it had an image that somewhat stood on its own, a halo sports car for GM the company rather than just Chevrolet the division. Anything Cadillac could try as a legitimate sports car would inherently have to top the Corvette in some way and that burden never plagued the likes of Mercedes where Mercedes was Mercedes and not a division of a corporation of multiple brands. The XLR was a legitimately good attempt at a Cadillac sports car, but being Corvette based was lost on absolutely nobody, and even if GM came up with something akin to it in their heyday the same problem likely would have persisted.

Cadillac probably would have been better off staying away from the sports car entirely after they missed the golden years of them, SL be damned, and just retained the image of stuffy large luxurious sedans, the Allante and XLR only served to showcase the brand’s weaknesses in the times they existed and it’s not like they were even necessary for luxury makes to field, chasing after Mercedes with the Allante was one of the many obvious chasing after _____ Cadillac unfortunately became known for in modern times.

That plays to the argument that the Corvette should have been a Cadillac from inception, making it a Chevy may be the core of this Deadly Sin.

The from a styling perspective, the ‘vette was neither Chevy or Cadillac and especially the early generations would have looked great in a Cadillac showroom. A Cadillac V-8 in the first gen would have been a much more fitting engine.

The Corvette in the Cadillac realm may have also moved the Division in a less stodgy direction over the years.

The problem with a real Cadillac sports car would have been in the powertrains. The Cadillac V8 was a great engine, but it might have been too heavy for a proper sports car. Under the old Divisional structure, a second engine (and a decent manual transmission) for a low-volume sports car would probably never have gotten corporate approval.

Chevrolet might not have been the ideal dealer network for an exclusive sports car, but that Division certainly had the powertrain for one.

And I don’t think anyone else did in 55.

While realizing there is more to it, the Caddy engine displaced 331ci in the Corvette’s 1953 inaugural year. The Corvette was up to 327 by 1962.

Given the eventual proliferation of engines from the Divisions, and the money frequently thrown at both the Corvette and Cadillacs, not to mention the various horse trading among the Divisions that occurred from the beginning of time, a Cadillac engine that took a different path from the main big car engine seems plausible.

1953 saw Cadillacs equipped with Dynaflows after the Hydra-Matic plant fire. That would have been an interesting Corvette!

Looking at a page of duckducked images, few are showing anywhere near the amount of wheel well as this one. Part of it is the lighting, but either most other people sized up their tires or this owner sized down.

It would have been difficult to put an emphatically-Cadillac nose on the small, simple body, but PF failed badly, as did the ’86 and ’92 Eldorado. Could anyone photoshop a ’92 Seville nose on it? If you can’t power dome the hood, the grille needs to show a Chad lower jaw (not dagmars).

What was with that uptick in sales in 1993?

I think that was mostly due to the cars getting the then new Cadillac Northstar engine in that final year.

I seem to recall either R&T or CD published a sketch of a sedan with the same styling cues, which I remember thinking was quite handsome. The rear quarter windows had a kick up vaguely reminiscent of the 67-68 Sixty Special. And the proportions were a predictor of the 1992 Seville.

As for what GM design was capable of versus the Allante at the time, there is the Reatta.

The Allante showed almost the same obsession with “cut line management” as Giugiaro’s Isuzu Piazza/Impulse. The front and rear bumpers were very well integrated. Even the fuel filler flap is well hidden. The details were all nicely done, but the proportion and dash-to-axle ratio dictated by the GM FWD platform doomed it.

I always felt that the Allante’s styling was the result of Pininfarina being told to “color inside the lines”; to very strictly adhere to GM’s corporate downsized new look. You know, “Do something just like this, but different…you know what we mean.” The general shape is very clearly thematically drawn from the 1986 “shrunken-head (Thanks for -that- visual, Paul!) Caddys.

The logic is obvious; a halo car must show resemblance to its lesser brethren so that they may benefit from its glory. Unfortunately this can go horribly wrong as it did with the Chrysler TC Maserati, where the halo car was dragged down to the gutter by the family resemblance and here, where the slab-sided look left an impression of ease-of-assembly being the priority over beauty. It’s a nice enough shape but has to be examined closely to be appreciated- at a glance it looks cheap and generic, in my opinion – not nearly as distinctive as the production 1987 El Dorado. I don’t care for the whacked-short rear section of the El Dorado, but otherwise it’s an elegant look.

I have never driven an Allante, but I did spend some time behind the wheel of an XLR – an exterior shape which I think is very, very good. However the interior of that car was just….wrong somehow. It was huge inside, but not with a spacious feeling, but an empty room feel. My impression was for some reason of being in a huge pickup truck with the roof cut off. The seats were nice but not cosseting – just bolted to the floor in the middle of an empty room.

The plastics were cheap enough looking , but that Zebrano wood on the console! It looked like some guy in his his garage had done a really nice job of putting 100 coats of polyurethane on some well-sanded plywood. I know luxury cars when I see them; some of my friends have luxury cars; and this, Sir, was more home-built kit-car than luxury car.

I can’t honestly say what would have been a better thing for Cadillac to have done at the time; they were just so far off the mark in those days, I can’t even imagine what they might have done to improve things.

Yes! That wood seemed to be randomly placed wherever there was sufficient space for a large piece of it. It somehow looked faker than the woodgrain in a ’76 Seville even though it was real. The rest of the interior looked like a DaimlerChrysler reject.

My favorite Alante story come from my Father. My dad had a lifetime of work in investment banking here in CT. Lots of people with lots of money (yuppies as far as the eye can see). One of his coworkers at the bank in 86 bought a new Allante. GM created a bizarre program that promised the trade-in value for the Cadillac would be the same as the SL. He bought the Allante at a discount from the local dealer (something like it was the verge of holiday and if the dealer sold it that night they got a big rebate from GM.) 2 year later the SL was worth damn near what he paid for it (and he tracked it he knew this was going to happen) so he traded it in on a new Deville for his wife and a check (I guess part of the program allowed for this) He always joked how he made more money on that deal then the GM stock he owned. If I remember a few years later he had a new Lexus SC.

An article I found on the program

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-05-22-vw-154-story.html

All of which adds even more to the deadliest sin thing.

This is another thoughtful and thought-provoking piece. I knew one woman who bought an Allante. A then-mid-50’s executive who traded an ’85-6 Sedan deVille, complete with gold badging and a sim-con roof treatment for a bright red Allante around 1990. It was really the interior that let it down in the worst way. Plastic-fantastic, with all those LED displays in the same green as your VCR clock and tons of little buttons that just looked like they would rattle around in their cheap plastic panels over any rough surface.

The photoshop of the ’86 Eldorado convertible in this piece gives me food for thought. Maybe Cadillac should have just built that. It probably would have appealed to the more traditional Cadillac buyer (who were really the only ones buying Allante’s anyway), it could have been done in-house or by ASC a’la the early Cavaliers, it actually looks better to my eye than the Allante’, and considering the abysmal quality of the Allante’s interior anyway, they may as well have dumped all that “techier” tech into a high-end Eldo ‘vert, given it some more Euro looking trim like the early ETC and called it a day.

Cadillac was attempting to repeat what they did in 1959-60 with the Eldorado Brougham, which was also farmed out to Pininfarina. They hoped Allante buyers would remember the exclusivity and prominence those cars had at the time with the Pininfarina name and being hand-built. Unlike the Allante, the Eldorado Brougham wasn’t trying to mimic any competition, and those cars did their part in maintaining Cadillac’s prestige, even though sales were low. In the end, the Allante was a huge sales flop, and never achieved its goal of knocking Mercedes Benz off its pedestal, performance-wise nor in build quality. And then there was negative publicity at the time of how inefficient the production logistics were, taking two trips across the ocean and back, for example, and other production obstacles.

As for the long-nose Cadillac concepts of the 1960’s, they were for a proposed V12 engine.

The Allantë did not look BAD. But it did not look SPECIAL… more like boring, actually, Italian (whatever THAT implies) or not. And GM sold it on gimmicks (shipped across the Atlantic on 747Fs) rather than substance which it did not have anyway.

It definitely did NOT look like it was worth what it cost. The pricing was adding insult to injury.

At least the (somewhat similar in concept) Buick Reatta did not cost that much more than the Riviera on which it was based.

Wayne Kady’s work seems to be highly ADMIRED by some in the car design community. I would note that elements of various Kady renderings did show up on certain Cadillacs over the years.

For more: http://www.deansgarage.com/2020/clasiq-designer-series-wayne-kady/

Personally I rather prefer Stan Mott’s “classic” CYCLOPS!!! :):) However, I owned 2 VW Super Beetles so what do I know??? DFO

Yes, I see the ’71-76 full size’s A pillars and windshield in the first Kady Caddie, Toronado blade fenders in the third, and the future Bustleback with their late 70’s standard wheelcovers.

deansgarage.com is a love fest of/by/for former American car designers. It’s where they and their acolytes hangout to congratulate themselves perpetually for their splendid achievements.

LOL Paul. Thank you for saying what I was thinking but could never quite put into words. The images a Dean’s are truly amazing, but some of the self-congratulatory back slapping is just so…self-congratulatory. Either that, or some of the designers had really, really bad taste. Most of their 80s-90s designs rather sucked IMO. The ONLY cars they really got “right” (from the styling perspective) in the last 40-50 years were the 77 B-C’s, 80 E’s and 81 A-specials on the GM side of the house, the ‘86 Taurus and the 90s ChryCo’s. Everything else looked a little weird. Saturn SL-1 anybody?

The Allante in the photos looks like the front tires are the wrong size.

It would appear that a Pininfarina concept car from the mid-seventies was the inspiration for the ’77 B-body Caprice. That worked for GM then. It’s too bad the Italianate Allante design couldn’t have formed the basis for a Caddy sport sedan. The front clip especially would have looked great as the new face of Cadillac.

These are purely styling exercises to test out concepts.

It seems to me that they tested the absurdly-long hood concept continuously for a solid decade or more. Slow learners, I have to assume. Or just an unrestrained obsession. We can see where that all led to.

I haven’t been called “Needlehead” since 5th grade. It says a lot about the rest of your comment, and others you’ve left here.

I’m not offended, but I will warn you that name-calling is a no-no here, just like it was in 5th grade. If you persist, you will have to go to detention and lose certain privileges, like commenting here.

Quite delighted to see this wasn’t a rerun, amazing that we’re up to #36, the hits just keep on coming. Err the misses anyway.

Love it or hate it, it makes a splendid LeMons racer:

If we’re attaching the “Deadly Sin” accusation to the Allante, my argument would be more centered on the ‘made it right and then killed it’ aspect all-too-common through GM’s history.

Viewed without the benefit of hindsight, the Cadillac lineup of the 1980s had to endure downsizing and pulling from the parts bin at every possible opportunity, while still being stuck with the same stylistic cues that appealed best to the demographic between “Retired” and “Dead”.

Despite all this, for something like the STS to emerge with some decent ride and handling characteristics bordered on miraculous. The stylists did what they could to buff off comes of the chrome and brougham but with that shape in interior, only so much could be done.The Allante was the stylistic leap GM needed to take with Cadillac. Yes, the lineup was still selling but not to the more desirable demographics, and with things really taking off for European luxury that decade Cadillac was losing respect in the global market. Witness how Lexus and Infiniti looked to Europe for their inspiration during those days. OK, you argue that maybe the leap wasn’t far enough; but I’d argue considering the day’s aesthetics, it was pretty damn far. And considering what ended up in the rest of the showroom in 1990s, it was great foreshadowing.

I think it was necessary for the Allante to be as expensive as it was not simply as a matter of cost coverage but for positioning. It showed this was a serious car. GM’s main failure in this particular circumstance was not accepting that sales volumes at that price point absolutely would be small (very clever bringing up the XLR – where they did the EXACT SAME THING).

Sometimes that’s the point. Dodge didn’t build the Viper to put one on every block.

My repeated point on this situation is if you plan to make a halo car statement, go in knowing you’re not going to sell a zillion of them. Just make sure engineering knows if we’re not going to break even on this, at least keep it reasonable enough where we can make it back on other products. In this sense I’d have viewed the Allante as a Production Concept.

Like you, I absolutely question the need for the very unique LCD and buttons interior design. At the time lip-service was given to the “full Allante experience” but considering the complete interior re-do that came with the 1990 Seville and Eldorado and looked less like your microwave oven, something a little less “mission control” (with NASA costing attached) could’ve shaved a little off the price and maybe been friendlier to potential buyers’ eyes. And it must be added, I know when faced with Cadillac QC of the day, I’d be more than a little skittish of anything that new-tech-electronic from them.

But back to that “Production Concept” idea, where the Allante was an adopted stepchild in the environment it arrived in. The Cimarron actually fit in better. But once the 1990 Seville and Eldorado broke cover that bastard was right at home. It was all one big happy family.

At which point the Allante was canned.

Unless there was some contractual obligation that only Pininfarina could build it and only with that interior and only the Air Bridge was allowed to bring it, I still say a refresh to make the Allante more common with the then-new Eldo and Seville would’ve brought GM a lot more credibility on the world stage.

For me, the Reatta was a true “Deadly sin” where the luxury two-seater idea all went wrong for GM. The pie wasn’t big enough for that and the Allante.

The Allante was a combination of Italian styling and efficiency coupled with GM reliability and brand panache.

Toyota took a page out of GM’s playbook when developing the new(ish) Toyota Supra. Like GM they had not developed a serious luxury sports car in decades. They turn to BMW to make it for them, coupling Toyota’s tasteful styling with BMW’s bullet proof reliability. What could go wrong?

It took me a few seconds to catch the sarcasm. I’ll just add that the Allanté seemed brilliant compared to the Buick Reatta.

Unlike GM however, the Supra has well outsold the Allante (2,800 for the second half year 2019, then over 5,800 in pandemic year 2020 and on track to be over 6,000 for 2021. And that’s just for US sales.

Additionally both BMW and Toyota have their respective versions built at Magna, so taking up zero of their own capacities in doing so along with likely having the exact production costs already laid out / agreed to in advance. Long-term reliability is still an unknown but I can’t see it being worse than a 1980s-1990s Cadillac, if likely not at Corolla levels. Then again a typical Supra buyer is likely very into their car and will probably be obsessive regarding maintenance and necessary repairs. Are BMWs actually unreliable these days or is it more a matter of needing a greater and more expensive maintenance regimen than the average Japanese car?

Of course there’s minimal value-add in buying out the majority of parts as well as assembly, presumably it only exists to provide some sort of halo car, to engineer and built it solo in house probably made even less sense financially so the choice would to not have it at all. Either way, Toyota can afford it better than Cadillac could, then or now.

I can imagine a 1980’s GM exec wearing his light blue shirt with starched white collar, silk tie, yellow suspenders and slicked back hair. His diamond cuff links glinting from the sunlight coming in through his penthouse window.

“Why the Allante has been a stunning success for us, the Allante has well outsold the Bricklin SV-1, DeLorean, and even the Yugo! And that’s just for US sales.

By having our bodies built in Italy, we are taking up zero of our own body stamping capacities in doing so along with having the exact production costs already laid out and agreed to in advance.

There are some who don’t believe this is Morning Again in America and the Allante is somehow not at Corolla levels of reliability.

But a typical Allante buyer is likely very into their car and will probably be obsessive regarding maintenance and necessary repairs. Are Allantes’ actually unreliable or is it more a matter of needing a greater and more expensive maintenance regimen than the average Japanese car?

Huh? The Yugo outsold the Allante about 7:1 in the US…But oddly all three of the brands you mentioned (Bricklin, DeLorean and Yugo America) did go bankrupt just like GM did, I wonder what the common denominator was. Toyota seems to be in no danger of the same, they can afford the occasional flight of fancy.

Whenever the Allante is mentioned here I always go to YouTube to re-watch the Married With Children clip of Christina Applegate and Tia Carrere doing the Bundy Bounce.

“The New Allante!”

I wonder if Cadillac paid for the product placement.

…which Wayne Kady seems to have lifted verbatim for the back of his ’80 Seville.

Cadillac was still pushing 16-cylinder show cars well into the 2000s before it became obvious that huge internal combustion engines (and for that matter, large sedans) were not the future. There’s a bit of Kady-esque style in this Cadillac Sixteen concept even though he wasn’t involved.

While not a 2 seater, this mid ’70s modern and tasteful LaSalle/Seville proposal that was never executed proves that there were GM designers with taste. Sure wish they had built it,

it would have been one that could have re-established GM as the true style leader.

One big problem was there were used e body Riviera convertibles around that completely outclassed the sad little Allante squaremobile in looks and comfort and usefulness. For what an allante cost it should have had more style than a Chevy Celebrity. the dash looked like the inspiration for the later horrible chevy truck dash

The Allante followed the route of the ’75 Seville, which almost the highest priced model. Though it had little content to warrant that price. It was priced so high because Cadillac thought that it would lend prestige. The Seville was a handsome car with restrained styling in the first couple of years. It could have easily been turned into a driver’s oriented car, but it wasn’t. The downsized ’79 Eldo was another car that could have been developed as an enthusiast’s model, FWD was not yet spurned as being too pedestrian. Cadillac should have just developed a four seater or shortened Eldo convertible, they could have sold a bunch of those.

I think the exterior of the Allante is fine, but the interior with those gauges and horrible rows of buttons is just awful. It was supposed to reference high tech, but any potential customer would have been wary of all those controls functioning past the warranty period. The front wheel drive power train was the kiss of death, FWD was now seen as worthy of only being used on econoboxes, not anything considered a premium line.

I suppose that Cadillac thought that the Italian connection would elevate their level of prestige to a point that made the high price viable, and would make Cadillac look like a World Class competitor. Cadillac has made good cars in the past. They will make more of them in the future, but they need to make the best cars they can at a profitable level. They will just not be able to build a flagship that measures up to the best in the world.

The Skylight has its frontal treatment straight from the later Humber Super Snipes, THe Allante doesnt look very special, its not the range topper expected from a luxury brand

Regarding your comment on Kady, here’s a 13min interview where he actually mentions that by sixth grade, he could draw all the GM cars…and then got a GM scholarship at design school. And then worked there for the next 38 years.

The interview is – er – unexciting, but worth sitting through as it might give quite some insight into the not-exactly-outlooking style of GM and its folk. (More frankly, I find some of his comments about the “expensive” or “almost snooty” look of his crass ’71 Eldo almost comical). And perhaps it speaks to why it was that lessons weren’t ever learnt. Can’t help but speculate that Pininfarina’s hands were tightly tied by such thinking in the Allante job, too: even in the rather dreary mid ’80’s, they were a better design house than this.

I’m familiar with his beginnings and career, having done a post on his life’s work here:https://www.curbsideclassic.com/automotive-histories/the-cars-of-gm-designer-wayne-kady-slantbacks-and-bustlebacks-from-beginning-to-end/

Thanks for the video link. It’s about what I expected; a bit dull.

Bobby Unser drove an Allante at the start of the ’92 Indy 500 – he even praised it !!

Good enough for him then it’s good enough for me!

And how much did he get paid for that?

They probably gave him one – a mixed blessing perhaps!

They probably gave him one – a mixed blessing perhaps!

Fortunately than GM has many blunders to its credit because I wonder what you could have written. If General Motors is such an “uninteresting” corporate, why tell us about it again? In addition, the idea of a FWD La Salle II was an early idea but not completed. It’s very easy to criticize but let’s not forget that the designers had only a few months to develop all these Motorama’s prototypes. Who could design innovative and functional cars in such a short time in 1954? Nowadays, even with computers, it’s always a difficult task. Apart the 1965 GM engineering journal (dedicated to the Olds Toronado), published to 10 years later, I have never seen no GM documents/ads linked to the 1955 Motorama, mentionning than both prototypes were front-drive cars.