(updated 12/31/2020)

Independent front suspension, air-suspension all-round, an ultra-light forward-set alloy cab only 48″ long, power steering, a complex fabricated frame that was 50% lighter, and the lightest diesel engine: This was the recipe for the most technologically advanced semi truck tractor in the world in 1959. It could haul over a ton of extra payload capacity thanks to its light weight, it was highly efficient and was the most comfortable for its driver.

The DLR/DFR 8000 sprung from the same mindset that created the air-cooled rear-engine Corvair, the “rope-drive” Tempest, Buick’s Aluminum V8, turbocharged Cutlass Jetfire, the Turboglide, and a raft of other engineering firsts at GM in the years 1959-1962. None of these survived long-term, and most were gone within a couple of years, including these GMC DLR/DFR 8000s. Intended to vault the competition through sheer technical overkill, they were the result of the oft-deadly hubris that permeated GM. In this case, the failure of the DLR/DFR 8000 led to the GMC Truck division’s terminal decline in the heavy duty field.

The GMC “crackerbox” COE did survive longer, until 1969, but only because a very conventional dumbed-down version was rushed into production to replace the DLR/DFR 8000, not unlike the 1962 Chevy II and 1964 Tempest, Skylark and Cutlass. Turns out what American truckers really wanted was cheap, heavy, average, but good looking, just like American car buyers. How did GM not know this?

COE (Cab Over Engine) trucks became popular in the mid-late ’30s, like this 1937 GMC semi tractor. There were several advantages, the two biggest being better weight distribution and of course a shorter overall length. That become the dominant factor as the trucking industry expanded beyond regional reach and had to deal with an arcane hodge-podge of different length (and weight) regulations in an increasing number of states. The best solution was a short COE tractor to meet the regulations of the most stringent state(s) the truck would have to operate in. Of course there were other advantages too, in maneuverability in urban settings.

This ability to meet the various state restrictions was of particular importance to movers, which had to potentially be able to go to any state, and explain why long distance moving trucks almost invariably had COE tractors.

The truck industry prior to the mid-late ’60s was divided into two markets: the far West, and everything else. That’s because the West Coast had drastically more lenient length rules, so that long conventional trucks like this 1940s Peterbilt dominated there.

Even CEO trucks out West often didn’t take advantage of their space efficiency, like this long wheelbase early Freightliner.

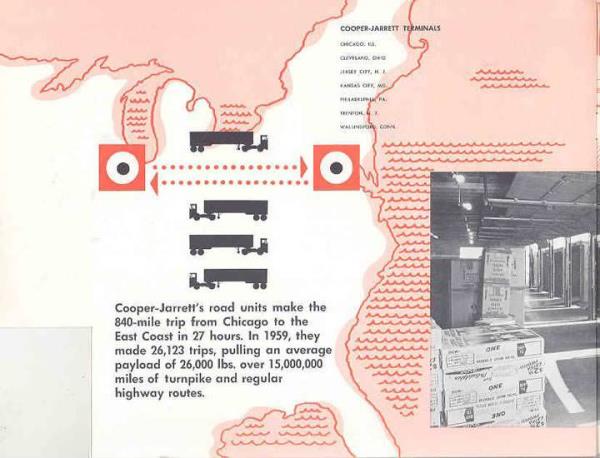

As we shall see, GMC’s DLR/DFR 8000 was clearly targeted to the eastern market.

In the East, the White 3000, the first popular tilt-cab truck dominated the COE market in the ’50s.

International got in the tilt-cab COE market in 1953. It soon spawned other variants.

Meanwhile, GMC, which along with International had for decades been the two top selling medium/heavy-duty truck brands, only had an older style non-tilt COE, dubbed the “cannonball” for obvious reasons. GMC was risking seriously falling behind in what soon came to be the dominant style of semi tractor.

GMC did leverage its great success with its air ride transit and highway coaches for the cannonball and other HD GMC trucks starting in 1957.

Both front and rear axles were suspended on air bags, resulting in a dramatic improvement in ride quality. The technology came straight from the buses. How many were actually sold with the air ride is another question. Not many, apparently.

But that just was a stop-gap at best. GM’s truck engineers went to work creating the ultimate COE highway tractor, one that would top the competition in every metric: weight, space efficiency, load capacity, and driver comfort. The “Tilt-Cab Cruiser” was first shown at the Chicago Auto Show in December 1958, and only as the cab-forward DLR8000.

This brochure from 1959 shows the DLR 8000 (left) with its aluminum cab in front of the axle and an ultra short 108″ wheelbase, which combined with its mere 48″ of cab length meant that longer trailers could be used in highly restricted states. It also shows the DFR 8000 (right) that was added later that year, which had its cab directly over the front axle, and also sat a bit higher too. According to the brochure, it was available in 108″ and 130″ wheelbase length. A very compact sleeper cab version was available in either configuration.

There’s very little detailed historical information about these trucks except from a few brochures and a few paragraphs at some forums. Even the definite book “GMC Heavy Duty Trucks 1927-1987” has precious little on them. GM press releases state that the DLR 8000 went into production in 1959, and the DFR 8000 was added sometime later in that year. This ad from 1959 only shows the DLR8000. And as we’ll see later, by 1960 a very conventional “crackerbox” with its cab over the axle like the DFR 8000 was added, which quickly became the only version offered.

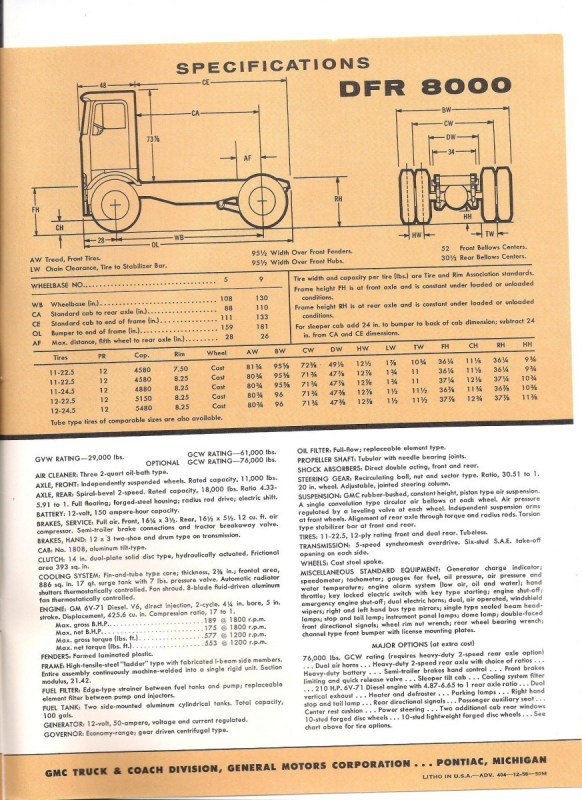

The DLR 8000 was a clean sheet design from the frame up. Its frame was quite unusual, as instead of the usual riveted C-channel rails with cross members, it was designed some 50% lighter due to being fabricated from specially formed steel components and then welded together. The DLR’s frame (upper left) was quite distinct from the DFR’s frame (lower right) with its deep X member. This was all highly unusual and ambitious. For optimum weight distribution, the DLR came (only) with the inline Detroit Diesel 6-71, and the DFR was came with the new V6-71, since it was shorter and as such would not extend past the rear of the cab.

The very minimalist cab was fabricated mostly from aluminum, with fiberglass fenders and front grille. The sleeper cab added a mere 24″ length; it’s not visible here, but the 30″ wide mattress makes a jog behind the driver’s seat, narrowing it down to 22″.

The very minimalist cab was fabricated mostly from aluminum, with fiberglass fenders and front grille. The sleeper cab added a mere 24″ length; it’s not visible here, but the 30″ wide mattress makes a jog behind the driver’s seat, narrowing it down to 22″.

The two different designs are more obvious here. The DLR’s X-braced frame (left) is even visible.

Here’s a good look at the independent front suspension. A traditional SLA (short arm/long arm) with ball joints.

More details on the front suspension and steering. Power steering was optional, something that was not at all common on big trucks back then, and for quite some time to come.

The standard 6-71 two-stroke diesel engines were rated at 189 gross/175 net hp @1800 rpm (DD diesels only sound like they’re revving fast because of being two strokes), and 577/553 ft.lb. of torque @1200rpm. The optional version with larger injectors had 210 hp. A five speed Spicer “synchromesh overdrive” transmission teamed with a two-speed Eaton rear axle. There was no twin rear axle version, and very few options. This was a very tightly specified truck for very specific applications.

Here’s the DLR specs. Unfortunately, there no weights given here, but I found it elsewhere: 9090 lbs.

The DFR was also available in a longer 130″ wheelbase.

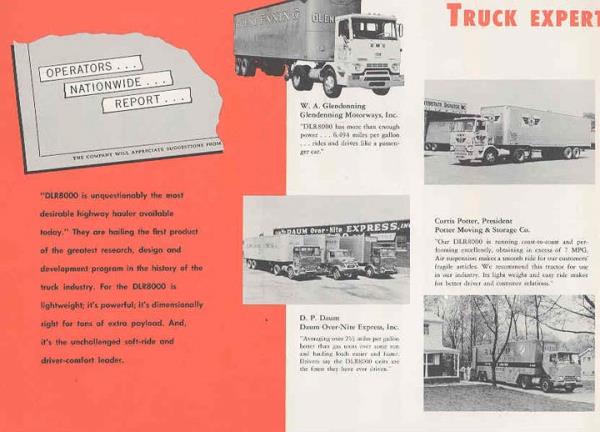

Per its specs, the DLR 8000 was aimed at the fast growing regional truck freight companies. Given that the industry was still fully regulated (freight rates set by the ICC), the opportunity to haul an extra ton of freight could directly impact profitability.

These operators primarily covered the cities and industrial centers of the East and Midwest. Cross-country truck freight hauling was still quite unusual, and if so, the loads were typically interchanged at Denver or other key hubs with West Coast freight companies. But this was all changing quickly in the ’60s, with the growth of the interstate system. The DLR arrived just at the cusp of the great long haul trucking boom, and was too inflexible in its configuration.

Note that these testimonials from operators are all cab-forward DLR8000s. It’s pretty safe to assume that the DLR outsold the DFR by a substantial margin.

Moving companies were another target market, as maximum volume that could meet the shortest state restrictions was desirable. As was the air ride suspension, which movers adopted as soon as it became available, to protect delicate cargo from damage. GMC crackerboxes were seen hauling moving vans well into the ’80s and even later. This one has an added “pup” trailer, since it’s operating in length-lenient California.

There’s only a handful of genuine DLR8000 images on the web. Here’s one with what looks like a 35′ trailer, common back then in many length restricted states..

And here’s one with a flatbed trailer.

A commenter left these two vintage photos of a couple of DFR8000 trucks that were in service for a company he worked for. The rear control arm for the air suspension is clearly visible, the hallmark of the air-suspension DLR/DFR.

And here’s the other photo. This truck was still in service in 1976 with over a million miles on it.

The technically advanced DLR8000 and DFR8000 were quickly supplanted and replaced by the DF 7000 (single rear axle)/DFW 7000 (tandem rear axle) trucks in 1960. They had the same basic cab as the DFR 8000, but were very much more conventional otherwise, and cheaper, too. The set-back front axle version (like the DLR) was not offered on this new series.

This over-the-axle tractor is what became commonly know as the GMC “crackerbox”. That nickname obviously reflects its utterly minimalist cab design, a curious contrast to what was coming out of GM’s styling studios at the time.

The frame was now a typical riveted C channel ladder affair, and suspensions were the usual harsh leaf springs, with a choice of two types of tandem axle suspensions (Page & Page Rocker or Hendrickson “walking beam”).

The air ride DLR/DFR8000 models were technically still available, but only through 1961, after which time they were dropped. A short run for a short truck.

Meanwhile the DF series quickly expanded, including the 7100 version with the new DD 8V-71 engine, making up to 318 hp. A 238 hp version of the 6-71 also became available in subsequent years, replacing the 6V-71, which had cooling issues in its early years.

Starting in 1965, the DF7000 series also offered the unloved Toro-Flow 4-cycle diesel as well as a gas engine, the 637 CID V8 version of the 60 degree GMC V6. Some folks claim the legendary 702 inch V12 “Twin Six” was available in the crackerbox, but that’s not actually the case. FWIW, the 637 V8 was just as powerful (275 hp), lighter and more efficient.

So why was the highly advanced DLR/DFR8000 so quickly abandoned? There’s only some anecdotal comments out there, but it’s easy to come to obvious conclusions. The independent front suspension apparently soon showed itself to be maintenance intensive. This was also the case with all the light/medium GMC/Chevy trucks that appeared in 1960 with their torsion bar IFS. We covered that subject here. Presumably the technology just wasn’t there yet to make HD truck IFS anywhere nearly as reliable as the traditional solid front axle, never mind the cost.

Although full air suspension was embraced enthusiastically by bus operators due to the big improvement in ride quality, truck operators were notorious penny-pinchers, and the additional cost was undoubtedly not justifiable. Who cared if the drivers had their internal organs deep-massaged eight hours per day? Air suspensions are extremely common now, almost universal in over-the-road semis.

In addition to those aspects, what undoubtedly undid the DLR/DFR8000 was its very narrowly-targeted one-size-fits-all concept, oriented specifically for medium/larger eastern freight haulers. It came only as a complete integrated package, with no wheelbase options, no tandem rear axles, and no drive line options. Other truck companies offered numerous versions, options and extensive customization. From some accounts, the DLR8000 sold poorly from day one, due to these reasons as well as its higher cost. That explains why GMC quickly rushed out the DF7000, a very conventional truck to suit the actual needs and preferences of its customers, not GM’s planners and engineers.

Although the DLR/DFR8000 had a short and unsuccessful life, the more conventional DF Series crackerboxes had a reasonably successful career on the highways of America, but it would never enjoy the dominant market share its predecessors did in previous decades.

They were tall and rather intimidating looking, so utilitarian and stark, and as such very easily identifiable. With the legendary 318 hp DD 8V-71, they were also considered to be about as powerful and fast as anything on the road at the time.

Some have claimed that the crackerbox was available with the 475 hp 12V-71 Detroit Diesel, but not from the factory for highway use. There was a special order for a number of these off-road rigs that used the 12V-71.

Here’s a few more crackerboxes in assorted roles. All these wonderful shots came from Dick Copello’s fabulous collection of truck photos, many he shot himself over the decades.

Here’s a haybox.

And another Bekins.

Let’s stop and listen to a crackerbox with a DD 6-71 and straight exhaust pipes working up a hill. This is a perfect example of why these are called “Screaming Jimmys”, as their 2-cycle operation gives them twice the exhaust pulses per rpm, making them sound like their revving twice as fast as they really are.

The crackerbox inspired similarly-boxy competitors from the other Big Three, as in this Ford W-series from 1966. This was considered to be a rather weak competitor in its field too.

And even Dodge jumped in, with its L series, from 1965. Given Dodge’s weak market position and the lack of any prior COE trucks, this was ambitious and a bit surprising. It didn’t help solve Dodge’s problems, and lasted until 1975 when Dodge exited the market.

Ironically, all of the independents’ COEs, like this Mack, all had a bit more style than these flat-planed boxy ones from the Big Three. Which may explain a whole lot why the Big Three all petered out in the HD market: image. Just like American cars started to lose their status to the imports, the Big Three’s big trucks also started to lose image and status compared to the independents.

This change really took off after the West Coast trucks like Kenworth and Peterbilt opened distribution in the East in the late ’60s. Their distinctive long-nose big-grille conventional trucks came to define the big American truck, and this image rubbed off onto their COE models too.

The DF Series crackerbox was replaced in 1969 by the Astro 95. It was conventional in all regards too, except for its styling, which it actually had. In fact, it was a leader and ahead of the curve, in predicting a turn away from such brutalist and utilitarian boxes. It was influential in that regard, and it helped keep GMC in the game for a while longer, until 1987, when GMC exited the HD market. A Chevrolet version, the Titan, was also built, but that ended earlier, in 1980.

Ford responded in 1977 with its CL9000, quite advanced in having its cab be separately suspended, as this one listing to one side makes quite clear. It was the solution that the Europeans have used for decades to make their COE trucks comfortable. But the market spoke, and Ford bailed in 1997, selling out to Freightliner.

Why did the once dominant GMC Truck division fade away after 1959? The DLR/DFR8000 was clearly a watershed, although it was inevitable anyway, as a consequence of GM’s management structure. Once GM became fat and happy in the mid 1950’s, it failed to appreciate that it was actually highly vulnerable, on all fronts. Instead, its fast-track executives were assigned very short terms at the various divisions like GMC, Opel, Frigidaire, etc., to essentially put in time, before their next more plum assignments at one of the car divisions and then a corporate job on the 14th floor. The guys doing the actual work at the non-car divisions and plants never got a proper voice or good leadership.

And here’s a smattering of those GM execs in 1959, basking in the reflected glory of their latest creation, which was destined to take the semi truck market by storm. How much do you want to bet that not a single one was capable of driving it?

Related:

CC 1962 Chevrolet C80 Dump Truck With GM’s Deadly Sin Independent Front Suspension

GMC Twin Six V12: 702 Cubes, 275 hp, 630 ft.lbs.

Chevrolet Titan: A Design Leader In The Big Truck Field

That was excellent. I didn’t know about these, and I’m not usually interested in the truck pieces (sorry Johannes D), but this told a good story, about how one can have a lot of great ideas, but nonetheless miss the market entirely.

There is so much going on in this piece. It’s amazing these trucks were produced as a “one size fits all” proposition. How many passenger cars did GM produce that way? So why trucks? It wreaks of “we know what you need”.

That the truck division was a stepping stone to more prestigious positions is likely the biggest factor in the unsuccessfulness of these trucks. None of those executives had any skin in the truck game.

Interestingly, it later worked out the opposite way. One reason why pickups became a stronghold for the Big Three and GM in particular is that the C-Suites cared deeply about cars and constantly intervened in their development while they let the (light) truck guys get on with things.

That’s crossed my mind also as things have indeed changed. It’s hard to see where being on the development of the Cobalt would have carried more prestige than being on the Silverado development team.

Wow, you really made me think, and possibly have a “Eureka” moment.

Maybe I, and a lot of others who don’t seem to appreciate modern pickups, just are so blinded by love of cars that we didn’t see the way pickups have steadily evolved to be their best selves, maybe because the “car guy” executives paid them little to no attention. We loved our first child so much that we neglected the other kids, to our detriment. With no executive oversight that “improves” a design of a car, or decides capriciously what would be best, the truck guys just soldiered on and steadily improved the product.

But, that also now explains how a lot of pickups are now oversized and garish to a lot of people. Instead of listening to the market, they now appear to answer to the management team, with their profitability and margin the deciding factor over all. They are now the favored child, and the attention is not doing them any favors.

It appears that if management is directly involved, the product usually fails. If left to the dedicated teams, the product is usually better and sells more. Maybe they need to keep management away from design and engineering, and let marketing only deal with dealers.

I have a different theory. EMD absolutely revolutionized railroading in the US with a revolutionary product. Part of that success was by severely limiting customer choices. All you could change was paint color. Remember, we are not talking consumer products, but commercial fleets. Maybe some EMD managers transferred to GMC in the 1950’s.

This was all fresh info for me, and fascinating stuff! I surely saw a few of these in my youth but did not pay much attention to big trucks back then.

I wonder about that welded frame. I had always understood that riveted frames allowed for some flex without the risk of breaking a weld or tearing the metal. I wonder if this might have been one reason tandem axles were never offered – a longer frame more subject to flexing would have been needed, which was perhaps something that the rigid welded assembly could not withstand?

In doing some research on another project, I learned that trucks was where Chrysler tended to dump problem engineers. I wonder if GM suffered from this at all. Even if not, it is easy to imagine the truck guys being a little jealous of all the engineering pyrotechnics going on elsewhere in the company. “Hey, lookee what we can do!” was probably a common mindset at the GM of that era. And as you note, it was probably not real “truck guys” who were making the decisions.

I just got Dave Dudley’s “Six Days on the Road” in my head…just passed a Jimmy and a White! I’ve been a-passing everything in sight!

Outstanding research and supporting imagery.

I don’t know if GM attempted to market the DLR8000 in Europe, but it may have been better received there.

Yes, I was wondering that. At 8 foot wide it would fit the size restrictions alright and obviously that type of cab-over was already the normal configuration. The same Detroit diesels were used in the mid 1970s Bedford TM range.

8ft 2 in or 2.5 metres is standard max width across the planet, why you ask, have a look at a shipping container they have to fit a truck for road transport without over dimension flags, Buses can be wider as bodies are usually locally built to suit the market but trucks are sold ex factory ready to go world wide.

Passing the tooling on to Bedford would’ve been a good way to recoup their investment, assuming they had the production capacity to build it.

Maybe there was a good market for them in the UK, sold as a Bedford model. Other than that, I don’t think so.

Back then, the market for heavy trucks was a regional / local affair. Up north, Scania and Volvo. The British had their own brands; many of them, as a matter of fact. So did the Germans. The French drove French, the Italians drove Italian, etc.

Even countries like Spain, the Netherlands, Finland, Austria and Switzerland had their own heavy trucks (Pegaso, Barreiros, DAF, Sisu, Steyr, Saurer).

Trans-European transport, on a large scale, had yet to start.

The big game-changer in Europe was the 1965 Volvo F88. Later heavy COE-trucks with continental success -some more than others- were the Scania 0 and 1-series (110/111 and 140/141), the DAF 2800-series and the Mercedes-Benz NG (Neue Generation).

The most successful big US cabover here: the Mack F-series. Heavy-haulage and intercontinental transport (Middle East, Africa) was their game. Thanks to the exchange rates, it was a rather cheap truck too in the seventies (for so much quality and durability).

I don’t think articulated trucks were very common in the UK then; seems many/most were rigids with trailers.

Quite right! They had to come up with a rigid truck chassis too. Trucks + full trailers were also still prevalent on the continent, around 1960.

Probably the most common articulated types in the UK up to late ’50s were the ‘mechanical horses’ (most commonly the Scammell 3 -wheelers) which majored on their abilty to turn in the tight spaces designed around horse drawn cart traffic. That began to change in the 1960s though trailer lengths were very restricted and that short cab would have certainly helped there, but generally speaking I would agree the market wasn’t really there in 1961. Ten years on it was very different with the fledgling motorway network growing rapidly and the hamorrhaging of traditionally rail traffic to articulated HGVs.

Paul, this is an excellent essay. I appreciate this very much. I sold GMC light, medium and heavy-duty trucks and also have sold Internationals, White, White-GMC (anybody remember those?), Volvo and Autocar. GMC Truck & Bus was a closely know division where we got much done through direct contact with the factory. It was a great experience. I remember when Mr. Leon Hess of Hess Oil said to his fleet sales representative that he would buy GC tractors only if Cummins engines were installed. GMC started installing Cummins. Thanks again.

My father-in-law (a retired trucker) owned a couple of White-GMC tractors – he quite liked them. Afterward, he owned a couple of Volvo tractors – he found them to be quite smooth riding. When I first met my wife in 1991 he was driving a GMC Astro cabover, and now that he’s retired he still keeps his AZ license (Ontario, Canada) up to date and still drives occasionally – usually dump trucks and the like.

Excellent article, thank you. The team that drilled a new well for me last September showed up in a 55 year old Crackerbox day cab with an 8-71. It’s the first Crackerbox I’ve seen on the road in decades. Well drilling equipment is rare and expensive so it’s cheaper to keep an old truck running rather than replace the entire rig.

Vintage equipment still in daily use really appeals to me so I thought it was really cool. But wow, it looks really uncomfortable to operate. As a former truck driver, I’m in in awe of the cramped, sparce cab, the noise of the big Detroit under your bum and the bone shaking over-axle driving position. I can understand the buyer resistance for an owner/operator in choosing such a truck.

Wow.

The Crackerbox was a common sight in my childhood but I never could’ve imagined it started out with IFS and front cab. Really enjoyed this deep dive and glimpse into GMC history.

Dang….Blatz Beer!!!

I from Milwaukee so I ought to know

Blatz beer tastes great wherever you go

Kegs cans or bottles, it all tastes the same

Blatz is Milwaukee’s finest name

You always remember what got you drunk the very 1st time.

Great piece! As someone who ordered class 6,7 & 8 trucks not so long ago, I can tell you customization is king. The variety of wheelbases, axle types, engine and transmission combinations available is mind boggling. There really is no such thing as a “standard” truck. If you have a chance, take a look at a line setting ticket or order sheet on any new truck. Your head will spin!

Fascinating. The specs on that 637 V8 caught my eye—7.5:1 compression? Why so low?

Because unlike a car engine a big truck engine needs to be designed to be driven flat out, all day every day. That means it is actually frequently running near peak VE and realizing most of its static compression.

Plus fuels of the era did not have the consistency we see today. So better to set it up to be tolerant of low octane fuel.

Truck gasoline engines generally had lower compression ratios than their car counterparts. I assume that running a gas engine full out all the time increased the possibility of pre-detonation, due to the higher heat. And they wanted to make sure it ran on the crappiest regular grade of gas.

Update: I see we both said pretty much the same thing.

Also a result of the combination of large bore and low rpm. The more time it takes for the flame front to move from spark plug to burn all the mixture, the greater chance of detonation. Aircraft engines, even with the highest octane fuels and dual ignition, still had very low compression ratios.

I just re-watched Smokey and the Bandit with my Grandson over the weekend he was amazed to see all the Ford, Chevy, GMC and Dodge branded transport trucks he had no idea had ever existed.

Great article! Good point about GM executives moving around a lot, this is still the case at Ford and GM at least. I recall reading about how Mark Fields moved around a lot, every 2-3 years before getting the top job. When a car program takes 2-3 years at least, how can someone really get the full experience? What is the likelihood that an executive will land right when a program kicks off?

I also seem to recall one of these GMC COE’s on the TV show Movin On, it can be watched on Netflix or elsewhere – Rosie Grier and his pal drove it as the bad guys giving Claude Akins and Frank Converse problems. A good show to watch just for all the location shooting and period cars of course!

Fantastic article of an interesting story. Amazingly how wrong them seemed to get it. It certainly seems they did not try to hard to revise it recover their investment.

Fascinating article Paul, thank you. I knew very little about these trucks despite being a big truck fan from a very young age. I recall the odd one on the highways around here when I was a kid.

The Ford CL9000 picture brought back lots of memories, being my Dad’s first highway truck that he owned. My job was to start it every day to let it build up enough air for the cab air bags to come up off the stops.

And if you had a bad airbag, it looked like the one in the photo.

Interesting stuff for sure. Never knew these started life with an IFS, 4 corner air, and such a frame.

I’m not so sure that GM’s hubris is entirely to blame. I think there may have been a little “brown, manual diesel wagon” going on. The one brochure does say it has ” every profit feature you asked for and more”. I guess they forgot to ask if customers would actually pay for those profit features.

As you mention the laws did drive demand to fit the most volume or payload in a given space or gvw and the engineers did their job to maximize those attributes.

I’m not faulting the engineers. It’s an excellent piece of engineering. It’s management that screwed up. They had them engineer a more complex and expensive truck that was suitable for just one slice of the market.

And issues with the IFS were pretty much inevitable, realistically.

I think the IFS was the biggest leap too far, as you said issues were pretty much inevitable. However air suspension, at least in the rear and aluminum cabs were ahead of their time and did become common.

I’m guessing that the frame was driven in part by that IFS so once that went away the frame could revert to conventional construction.

Agreed. GM had been building air ride buses since 1953, in large quantities, and putting them under their trucks starting in 1957. That’s not the issue.

Agreed also about that frame: it was clearly designed for the IFS.

The aluminum cabs were not “ahead of their time”. Several truck makers had been using aluminum cabs before GMC did.

Thanks for all the great info and the great link to the Dick Copello photos. I will be spending a lot of time on those!

I always liked the GMC 9500 and Brigadier styling. For that matter most GM styling has appealed to me over the years. There must be some common design element that appeals to my subconscious that I cannot identify…..or a mutated gene that I have.

Great story as usual. Yeah, I’m sure none of those buffoons could drive that truck. Some of them probably don’t even drive themselves to work. And they all most likely have booze on their breath, given the corporate mindset of the ’50s.

This is really a double edged deadly sin, it missed the mark by trying to innovate, and ultimately the lesson to be learned was “don’t innovate!”

I don’t think I have ever seen one of these trucks before, even the longer lived crackerbox successors. I always enjoy the sight of COE trucks but no kidding that there’s not much GM signature style in this one. Even the Dodge at least added some flare with the D100 like pie pan headlights

Both the DLR and DFR made it into production, I saw a restored DFR at a California truck show a few years ago. There was also a DFR 8100 that featured the 8V-71 it in. Very rare I am told, and I can’t say as I have ever seen one of those in person. Biggest problem with these trucks was their high cost, which really wasn’t justified by the unique features. True that they were only offered in single drive cabover configurations, but at the time that was by far the most common tractor configuration in much of the country. The more conventionally designed DF series was successful and lead on to the Astro 95 cabover in 1969. The Astro 95 was a great success and sold well for many years. I would say the DLR/DFR was a failure, but I think it’s a stretch to say they lead to GM’s abandonment of the heavy truck market. They had some of their best years in the later 60’s and 70’s with thoroughly conventionally designed trucks like the Astro 95, General, and Brigadier. Lesson learned. Nonetheless, all the ‘Big 3’ eventually figured out that these types of heavy trucks were not something that could be effectively manufactured on high volume assembly lines (far too many options and hand-work) and didn’t generate anywhere near the ROI that light and medium duty trucks did.

Both the DLR and DFR made it into production

It seems more than a bit odd that if there’s a genuine restored DFR8000 or DFR8100 out there that it/they never showed up in the very many Google searches I made. Zero responses to that.

I would need some proof of that before I change my conclusion. I realize that it’s possible some were made, but I have my doubts. I would like to know for sure, but it needs to be verifiable.

Are you sure it wasn’t a DF series truck? You actually looked under it and saw the IFS and air bags. No pics?

GMC’s market share was never as high after 1960 as it had been. Sure, they sold a good number, but the truck market was expanding very rapidly during those decades.

Don’t have any pictures that I can find. Did have air IFS. For clarification:

DLR 8000 had a set-back front axle, 6V-71 engine (V-6).

DFR 8000 had a set-forward front axle, 6-71 engine (in-line 6).

DFR 8100 was a DFR 8000 with an 8V-71.

GMC nomenclature was D=diesel engine, L=cabover with set back front axle, F=cabover with set forward front axle, R=air suspension, 8000 GVW series designation.

I’m familiar with the nomenclature. It’s all spelled out in the post, more than once.

The odds of there being both a restored DFR8000 and DFR8100 at one show are infinitesimally small, even if they were actually ever made. In fact, good luck finding a restored DLR8000 on the web; extremely rare, yet they were built for several years at volume. I’ve looked at large numbers of truck show images and none of these two. The few restored crackerboxes all appear to be later versions, which of course were built in drastically larger numbers. I am highly dubious.

I am sorry, I should have been more clear. I only saw a DFR 8000 at that show, not a DFR 8100. The DFR 8100 version, if it was produced, must have indeed been in very small numbers.

The company i worked for had three DFR8000 trucks i will try to attach a picture this truck is a 1961. This truck had a 6v-71 detroit diesel.

Larry, thanks adding this photo. It’s the first photo I’ve seen of a DFR8000. Yes, these came with the 6V-71, to fit under the non-sleeper cab.

I am attaching two more pictures the front of the 1961 the other truck is a 1962 these pictures were took in 1968. The last time i saw the 1961 truck was in 1976 it was still in service it had over a million miles on it.The picture of the 1961 did not come thru that truck in that picture is a 1962 these trucks had sleepers they were about 22 inch.

This is really great work! I have to digest this in parts, simply too much goodies for one meal…

Great post Paul, Ive never run across these in the wild only in magazines, It does show GM engineers knew something back then, now that there is a driver shortage over most of the world driver comfort and ease of operation of trucks gets drivers to sign on and stay 14 hour logbook work periods are usual over here and our roads once you leave the minimal motorways are not smooth they are to put it nicely bloody awful so a rough riding truck isnt going to attract drivers, Ive just been driving such trucks, its tiring.

The Bekins with pup is the oldschool A train over here not seen anymore absolute bastards to back and not hugely stable going forward either, the back trailer tends to wander.

GM was simply ahead of the curve with these air ride low tare trucks a good thing usually but in this case too far ahead of the curve, Pity they had some good ideas most of which have since been adopted industry wide,

Air suspended cabs are quite nice but scary at first I went from a Navistar conventional tractor unit to a FH Volvo with no warning the cab swaying around on turns in the Volvo was unpleasant to say the least I’d only driven the lower FM model up till then, check mirrors, curtains still standing upright ok were all good, Ive driven them since without a lazy cab airbag or two and they are ok,

Enjoyable read, thanx.

What a superb piece on something I knew little about. American trucks have always had a fascination for me, and to see these in detail is a real treat. Thanks for sharing.

One observation is that, in the US and the UK, companies can be car builders or truck builders. GM, Ford, Dodge, Leyland, GM Europe and Ford Europe all bailed out of truck building, whereas Daimler-Benz, Volvo (cars now gone), Fiat and Renault (now sold of course) managed both, and VW have successfully bought into trucks.

Actually Leyland do still build trucks, but they’re part of Paccar and the name on the front is DAF.

Unless you’re in India where there’s Ashok Leyland.

And I’m led to believe those “Leyland” DAF LFs have axles made in Glasgow by none other than Albion.

(Part of American Axle but the sign on the plant still says Albion)

Great article, I worked for the GMC Truck and Coach Division from 1978 to 1986. Got laid off when the HD truck division was sold to Volvo. Only worked on one Cracker Box in my career. It is interesting how the trucks went from last inline to the front of the line. Cars got fuel injection around ’81, light truck didn’t get it until 86-87 and we got the junk not the good stuff. Fuel injection didn’t show up until later in the medium duties and again we got junk. The old Suburban hung around one year longer in 87-88, it was still selling well (no competition) so why not keep selling the junk. Heavy trucks were doing OK but GMC was constricted by plant capacity and old product. The General was a decent truck but it was to expensive for the every day truck. Detroit diesels were another problem, no longer competitive with Cat and Cummins. I believe they developed the 60 Series engine so they could sell the engine business. That was probably why Ford developed the truck that replaced the Louisville trucks, new product, sell the product. I remember the big shot from Detroit telling us GMC was in a fantastic position, “We have our own engines and transmissions, vertical integration.” Except nobody was buying our engines and the Allison transmissions were to expensive, not very fuel efficient and not very reliable. This “big shot” went on to ruin Oldsmobile with a little help from his friends.

Of course GM went on to kill its medium duty and HD light duty trucks too.

They are working with International now to revive their medium duty trucks.

It is amazing how the big three did manage to build the ugliest HD cabover trucks in the sixty’s.

As some one else mentioned the HD product options are mind boggling and you were doomed trying to build such a limited option truck, The thinking at GM may have been,

” Build it and they will come.”

When International put robotic painting in their Springfield plant there was over 200 shades of red available.

There was also so many truck manufacturers that you had to compete with.

Large fleet would say, I want Detroit 60 series engine, come back when you offer it.

I drove a 68 model in 1974 it had been riden hard and put up wet. The previous owner used it for short runs but couldnt stand the noise. Driver comfort was not a consideration then so my boss bought it for a yard tractor which i used all day to spot trailers. Sitting over the axle driving in a potholed gravel yard beat you up pretty bad and with no insulation the6-71 with reach left you deaf within 15 minutes. The aluminum cab was an echo chamber and hot in summer and cold in winter. Mechanically simple it always started and didnt breakdown. Never a day off. The only redeeming feature was being low it was easy to get in and out of. Not inconsequential for hooking trailers all day long.

The non-air ride crackerboxes have a rep for being hard riding, and they were all terribly noisy. If you look at those brochure images of the inside of the cab, it looks like there was no insulation to speak of. And the DD was notoriously loud.

Fantastic article Paul! These are trucks I only knew about in passing so it’s nice to read an in-depth look. The engineering of General Motors during this era is quite fascinating. For that brief period form the late 1950s to the early 1960s GM seemed to be very open to trying new ideas. But of course after most of them did poorly in the market place the GM reverted to being conservative. I find it interesting how quickly this change in mindset took place.

Clearly, the engineering in these trucks was quite ambitious. The frame design is something I find interesting in these trucks. The welded plate I-beam construction over stamped c-channels is very unique. The X-brace clearly would add significant torsional rigidity, which would work well with the independent front suspension. I also find it interesting that the X-brace was only used the the DLR trucks and not the DFR trucks. The advanced frame design and then reversion to conventional frame design is paralleled by the pickup line from 1961-1966.

i agree with you that GM’s hubris was at blame here. While I am sure many of these “profit” saving features were things that operators wanted, the extra upfront cost to obtain these features was not. The low bidder usually won. The lack of customization was clearly the other big fault. They weren’t listening that closely to truck fleet operators. At least some of its features, like the air ride, became common place later on. The independent suspension seems like a good idea, but I wonder how much it really improved the ride? With the high spring rates required, I doubt the there would be much independent movement. It was kind of like when Ford had the “independent” leaf spring Twin-Traction beam front ends on their older HD 4×4 pickups. They rode so rough, the solid axle trucks on the next generation Super Duties that replaced them were actually better riding.

reading the specifications sheets . heater and defroster were additional cost options? was the conduction of engine heat normally enough to keep the cab warm and windshield clear?

That was the case for essentially all cars and trucks back then. If you lived in Florida, you could save a bit of money. 🙂

Absolutely fascinating piece Paul, thank you!

I can’t help but admire GM for trying. As Bryce says above, they were ahead of the curve in the engineering.

Terrific piece. We got no such trucks in Aus.

I wonder if this is a DFR8000? It’s labelled as “1960 GMC Crackerbox”.

(page link is here, some Poncho enthusiasts in Maine who it seems go to this show)

http://badgoat.net/CRH_homepage/ATHS/Springtime_Truck_Show/Springtime_2017/Springtime_2017_01.htm

I think not, because on the air ride DLR/DFR the long and low rear trailing arm for the rear suspension is usually quite visible, as it hangs down well below the rear axle centerline. My guess is it’s an early DF7000.

The survival rate on the IFS trucks appears to be nil or close to nil, because of the problematic front suspension. They were pretty much all junked early on. Where are you going to get parts for one?

The same thing was the case for the 1960-1962 IFS medium/heavy GMC/Chevy trucks. Folks weren’t happy with the IFS issues, and tended to junk them early. They were not ideal for the long haul. I hadn’t seen one in decades, but finally found one and I’m going to do an update of the post about them. Very rare,although built in large volumes unlike the DLR8000.

Update: looked it it closer in magnification, and more sure than ever that it’s not an air ride.

As a technical question, why did the DFR have the V6 engine instead of the I-6 like the DLR.Was this to minimize bumper back of cab (BBC)? That seems the most likely reason for the shorter engine since it would make the truck more nose heavy.

That’s the obvious logical assumption and the same one I made.

Outstanding post, Paul. I’m not a truck guy, but you had me at “Deadly Sins”. And boy did you deliver!

One has to wonder what they put in their pipe tobacco in Detroit back in the late 50s. Between these trucks, the Edsel, the 59 GM line-up, the Corvair, the Continental MKIII, the Packardbakers, the weird Exner stuff… Such a fascinating era.

It strikes me that GM wasn’t that far off by aiming at a segment of the market but the slice they (and Ford, and Dodge) should’ve aimed at was small fleet operators. Local utility companies and small manufacturing outfits with an in-house sales team. The Big 3 really never leveraged what could’ve been a huge advantage of a one-stop shop for outfits that ran one or two heavy-duty trucks alongside fleets of pickups, vans and passenger cars. For them, one sale/service contract with one dealer would’ve been a significant selling point.

FWIW, here’s a “DFR” listed for sale in Albany, NY, 1966:

Leave it to you to prove that the DFR8000 really did exist! You’ve solved a mystery. It rather makes sense, given that it’s shown in the brochures. But there’s no vintage ads or other evidence. Until now, that is.

Thanks!

You’re very welcome, Paul—I learn a ton from your research and deep thinking and writing, and it was a lucky stab today for me in the want ads of our childhoods. BTW, on eBay there’s a photo of a “DFR 9000,” whatever that adds to all this.

Happy New Year to you!!!!!!!!!

And a “DFR” ad in Philadelphia, 1961:

One more newspaper-search assortment:

Here is a DFR7000 owner’s manual:

https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/1959-gmc-crackerbox-truck-operating-1869257024

I did see one at an ATHS show back about 15 years ago. 6V-71, air ride IFS, welded frame rails. Fully restored, it was a light blue similar to what Global Van Lines used to paint their trucks.

My mistake, DFR8000.

Shot of GMC Parts Catalogue showing base equipment of DFR8000 ‘N’ series

Image .jpg won’t load.

I have amended the text to acknowledge that the DFR 8000 was produced, given that new evidence has been brought forth in the comments.

“There was no twin rear axle version” – Well of course there was. It may have had a different model number, but they sure had tandem axles available.

The DLR8000 and DFR8000 were available only in single axle i have only seen one where the frame was added on with a tag axle they told him then that it would not work but it lasted for several years. These frames were light weight and required some welding and repair on them in there later years.