In July 1993, I had the good fortune to attend the First Russian International Autosalon in Moscow and call it work. I found the name of this first-of-its-kind event to be a bit of a misnomer, because the show was far more Russian than international, displaying mostly Russian cars that were infamously obsolete and badly made, and trucks from Russia and other former Soviet states. The massive trucks on display impressed me, though, so I took close looks at several of them and left with their brochures, including one for the MAZ-79092, made by Minskiy Avtomobilniy Zavod (Minsk Automobile Factory) in Belarus, a vehicle that I later realized I had seen before.

This truck was a derivative of the MAZ-543, designed in 1959 as a specialized military vehicle for carrying missiles. A forward control 8×8 chassis powered by a 38.9 liter diesel engine from the T62 tank, it first appeared in public in 1965 as a carrier for the R-17 Elbrus (NATO name SS-1 “Scud”) short range ballistic missile. The MAZ-543 made its mark on history as the mobile Scud missile launcher used by the Iraqi military during the Gulf War of 1990-91. Iraq also used them during the “War of the Cities” campaign of the Iran-Iraq War, in which each country launched air and missile attacks against the capital and smaller cities of the other. The MAZ-543 continues to be found at the center of international disputes, as Syria, Iran and North Korea each still use it as mobile launcher for ballistic missiles.

Katyusha rocket launchers on Studebaker US6 trucks at the Victory Parade in Moscow on June 24, 1945 that commemorated victory over Germany. According to Russian sources, ZIS assembled these trucks from parts kits provided under Lend-Lease.

MAZ had a specific niche in a range of truck manufacturers that the Soviet Union created after the Second World War. After relying heavily on American trucks provided under Lend-Lease during the war, the Soviet Union invested significant resources after the war in expanding its truck industry in order to meet its own needs. ZIS (later ZIM, finally renamed ZIL), which predated the war, and Ural (full name UralAZ), which had been created during the war using ZIS assets evacuated from Moscow to the Ural Mountains, expanded to produce 4×2, 4×4, 6×4 and 6×6 military and civilian trucks. Heavy military trucks were the responsibility of MAZ, which had produced its first vehicles in 1947. Tractor-trailers and other heavy civilian trucks became concentrated in KAMAZ, whose production line started rolling in 1976.

MAZ built a comprehensive range of heavy trucks for military use: 6×6, 8×8, 10×8, 10×10, 12×12, 14×12, 16×16, and 24×24, with capacities of up to 220 tons. Multiple wheel steering, such as the 12 wheel steering of this 16×16, helped to increase the maneuverability of these long vehicles. A drivetrain with a gas turbine engine and electric drive was introduced in the 12×12 in 1978, the 24×24 in 1985, and the 16×16 in 1992. They were from a different world than Soviet civilian cars, living proof of the massive investment that the Soviet state made in military equipment.

Civilian use of MAZ trucks, although not originally planned, became significant. The MAZ-543 that became known in the West as a mobile Scud launcher became heavily used by the oil and gas, mining and logging industries in Siberia, which needed its heavy payload and off-road capability. The oil and gas and mining industries that dominate Russia’s post-Soviet economy were built on the backs of the MAZ-543 and its successors.

The 12×12, 14×12, and 16×16 chassis were carriers for Soviet mobile ICBMs, and Russia continues to use them for its mobile nuclear missiles. Shown here is a current Topol-M mobile ICBM on an MZKT-79221 transporter-erector-launcher, produced by MZKT (Minskiy Zavod Kolesnikh Tyagachei, “Minsk Wheel Tractor Plant”), a former subsidiary of MAZ that was spun off in 1991.

The fall of the Soviet Union changed MAZ, which faced a new world in which demand for its heavy military trucks would be dramatically lower. As noted above, six months before the fall of the Soviet Union, in February 1991, MAZ separated its heavier and lighter truck operations by creating a subsidiary called MZKT for the MAZ-79092, MAZ-79221 and other primarily military platforms, which it then spun off. MZKT marketed these chassis for civilian use under the appropriate brand name “Volat” (“Giant”). MAZ shifted its product line to focus on civilian trucks in smaller size classes and on buses.

This MAZ-79092 brochure was from the transition period of the early 1990s, showing a military design repurposed for civilian use in 1992. It prominently features the Volat name but does not yet refer to MZKT.

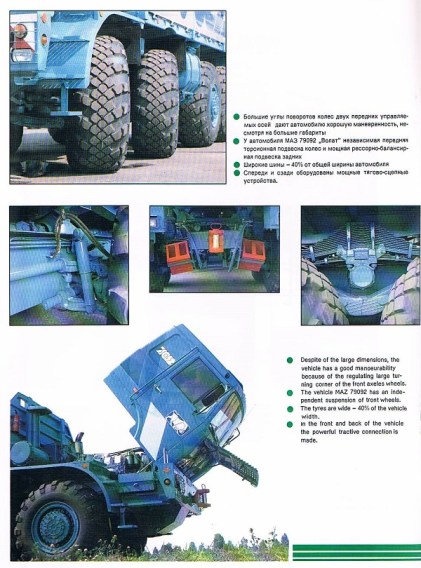

Showing its military heritage, the MAZ-79092 had a configuration intended for off-road use. A 22,000 kilogram (24.25 US tons) rated 8×8, it had a 470 horsepower diesel engine, 9 forward gears plus reverse, a two speed transfer case, and a central tire inflation system for low traction situations. The four front wheel steering system allowed a turning circle of 13.5 meters (44.3 feet) on a vehicle 10.52 meters (34.5 feet) long. Off-road performance most likely was excellent.

The suspension system was interesting as well, with independent suspension on the four front wheels and solid axles with leaf springs on the four rear wheels that carried most of the weight of the cargo.

A “reliable and economic” V-8 diesel engine powered the MAZ-79092, although like the outdated statement, “it is made in the USSR,” the claim of reliability and economy may have based on old standards. The YaMZ 8424 V-8 diesel engine was made at the Yaroslavskiy Motorniy Zavod (Yaroslavl Motor Factory) in Yaroslavl, Russia, which still produces engines for trucks made in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

The cab above the engine showed an attempt to meet the demands of civilian users. The driver’s seat appears to have a suspension system, as used in bus and truck driver seats in the West, for greater driver comfort in what must have been a hard-riding truck. Two bunks and a small refrigerator would have allowed the cab to be used as a sleeper on long drives or at construction sites.

If the 22,000 kilogram rating of the MAZ-79092 was not enough, or if nothing short of an ICBM transporter would satisfy your craving to out-do the Humvees that everyone else bought after the Gulf War, there was also the MAZ-7919. A 12×12 rated for payloads of 50,300 kilograms (55.45 US tons), the MAZ-7919 was a missile transporter chassis made into a civilian truck in 1988.

MAZ could produce a custom body for the MAZ-7919 chassis to meet the customer’s requirements, upon request. Or, as this brochure printed in 1990 stated in pre-1991 quality Soviet English, “Our advice on positioning of the platform body made at the Customer’s request help in rationally using the chassis and solving transportation problems to best advantage.” MAZ’s marketing skill apparently lagged behind its technical capabilities during the early 1990s.

Whether the MAZ-79092 and MAZ-7919 sold well in post-Soviet civilian markets could not be determined, but MAZ survived its transition from state ownership and military production to private ownership and civilian sales during the 1990s and continues to produce trucks and buses. It has done particularly well with buses, producing its 10,000th in 2009 after making its first in 1993 and needing seven years to produce its first 1,000. Since 1997, MAZ also has been in a joint venture with MAN, the German truck and bus manufacturer, producing MAN-designed trucks and loaders and giving the automotive world the delightfully silly-sounding brand name “MAZ-MAN.”

In a sense, MAZ has swung 180 degrees since the fall of the Soviet Union. The official founding date of the company is July 16, 1944, a day when automobile repair workshops in Minsk reopened a few days after the liberation of the city from three years of German occupation. The enterprise grew from producing military vehicles, including transporters for Soviet nuclear missiles that were part of the balance of terror that held the fate of humanity hostage during the Cold War. Since 1991, MAZ has survived by making trucks and buses for ordinary civilian use, and it has become a partner with a German company that once was a leading producer of Panther tanks, trucks and other military equipment for the Third Reich. MAZ is a company that has beaten swords into plowshares, and its evolution is one step toward correcting the mistakes of the past.

I like it though other than off highway logging operations I cant see a local use for one, too wide for regular roads and too heavy laden for our axle loading laws I’m not holding my breath to see one live.

You are right about these machines being too heavy and technically complicated to have much civilian use. Aside from size and weight, the complexity of these 8x8s, 12x12s and others, with their multiple drive and steering systems, must have led to very high production costs and an arduous maintenance schedule, all for off-road capability that is rarely if ever necessary in commercial applications. These vehicles are technically impressive, but outside of a cost-is-no-object command economy and/or an army with a large budget, they could never have existed.

Oh believe me, that off road capability is anything but “rarely necessary” in Siberia. The endless swamps and forests with rudimentary roads cut through them are literally impassable during certain times of the year.

I think the go-to vehicles for gas exploration tend to be smaller, cheaper rigs such as the Ural 6×6, as well as tracked MT-LB.

Feel free to go on youtube and search for “siberian offroad,” the sheer will and stubbornness (and foolhardiness one might argue) of the Russian character is on full display.

Good point – Russian conditions, especially mud during spring thaws, are far more difficult than what will normally be encountered in the US or Western Europe. I was thinking of places like the US, Western Europe, and New Zealand when I made my comment, not Siberia where there are very long distances with no roads, and snow and mud are both very deep.

I have seen some Russian off-road driving videos, and they are impressive. This logging truck video was especially memorable. The truck is a Ural-375, I believe.

Impressed, that second truck was never set up to be a logger but it does the job ok. Yeah where there are no roads these things excell.

Oh; I’ve almost literally grew up amongst these trucks – on the 12th Military Base vehicle repair facilities in Tbilisi, Georgia where my Granddad was a Senior officer … not many are still around though, as they guzzle quite a lot of high-octane gas.

Yeah those are Urals for the most part, the truck standing up on its “hind legs” is an old Zil 131 army truck. Back in Novosibirsk (city in Siberia that my family is from) there is an old army base nearby in Berdsk that has literally a mile long stretch of rusting Zil 131s, old mothballed stock left over from the Cold War.

One area of automotive design where the Soviets really nailed it was their military trucks. The funding came out of defense budgets, I think that’s what made the difference. Stupefyingly rugged and durable, the compliment to other Soviet military gear. AK47s on wheels.

Resupplying remote gold mines, delivering coal to remote villages, Siberian truckers make the guys on “Ice Road Truckers” seem just a bit pedestrian:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-JS23D69aWo

That video is long, but I will eventually finish it – it’s quite an interesting look at the extreme conditions that exist out there.

I have briefly passed through your hometown of Novosibirsk, although I saw it only through the windows of a train during a trip from Moscow to Irkutsk on the Trans-Siberian. Were your parents associated with the big university there?

I see that you have a Zaporozhets as your thumbnail photo, and I believe that you have commented in the past on your family’s ownership of a ZAZ-968. I would like to write an article on the Zaporozhets models made for individuals with missing arms and legs, for Defenders of the Fatherland Day on February 23. I have some original Zaporozhets literature and enough Russian language internet material to describe how they worked, but never having actually seen one of the models for the disabled (my Zaporozhets experience is one “taxi” ride in a normal ZAZ-968) or heard from anyone about the reality of obtaining or owning one, I would like to find some anecdotes about the ownership experience. If you can help, let me know!

Yes my parents went to college at NGU, both got their PhDs (dad in high energy physics, mom in genetics). Both are actually from incredibly rural families originally: my dad grew up in a village near Khabarovsk, my mom from a village near Biysk.

Yes the zaporozhets is actually a 966, a 1972 build with the 40hp engine. My dad has stories for days about acquiring spare parts for that car during Perestroika days. I think I’ve told some stories on here before about welding up mufflers out of stainless steel left over from the particle accelerator where he worked, and standing in line for tires (2 to a person!). We have the original owners manual that details all of the different variants for veterans (missing left arm and left leg, or right arm, or both legs, etc). WW2 left a HUGE amount of handicapped vets in the Soviet Union, hardly surprising given the scale of the war. My father was raised in part by a one-legged WW2 vet, his biological father having been a victim of a fatal hunting accident.

I have seen your previous comments about your family’s Zaporozhets, including the spare parts and exhaust pipe story. Your family’s car must have had one of the highest quality steel mufflers in the history of the automobile!

I may be interested in scans of the ZAZ-966 owners manual diagrams of the various variants of controls for different levels of missing limbs. Contact me at robertkim99@hotmail.com so that we can discuss further.

Even with military hardware, the Soviets definitely couldn’t afford cost-no-object specification (certainly not compared to some of the gold-plated ideas floated here in the late ’50s).

What I think had more to do with it was that certain projects deemed high priority became subject to huge amounts of political and personal pressure. (Greg Goebel’s account of the Ilyushin Il-2 ground-attack aircraft includes a well-known story about how during the war there were early production delays due to technical problems, prompting a personal telegram from Stalin that basically accused the designers of personally hampering the Soviet war effort with their delays and concluded, in effect, “Don’t make me ask you again where my planes are.”) Sometimes, there were also certain technical features Soviet engineers wanted to meet the military specification but couldn’t quite make work for whatever reason, at least not quickly enough to satisfy the political pressure.

Those kinds of conditions tend to lead to engineering or software kludges: It’s not the way you would have preferred (or even intended) to do it, but it works well enough to keep you from being sent to Siberia and/or buys you some time. It wasn’t uncommon for a piece of hardware to nominally enter service in a fairly crude and barely workable form, followed months later by a heavily revised version that became the definitive production model. On the other hand, some kludges remained in service for decades, at least until the military’s frustration with the maintenance requirements or design quirks filtered up through the ranks.

(Before anyone feels too superior, I think that’s pretty much how commercial software development works in the West today, with the possible exception of the risk of being sent to a gulag or sharashka.)

I’ve always found these massive, multiple axle machines fascinating. A very different approach to a heavy hauler which makes sense given the rugged terrain requirements and military heritage.

The US Army has a similar 8×8 truck called a HEMTT (pronounced “hemmit,”), although far lighter with only a 10 ton rating. It is considered a heavy truck by US military standards, the heaviest off-road vehicle in the inventory, I believe. The US armed forces never used mobile ballistic missiles on the scale of those used by the Soviet military, so it did not have a need for similar vehicles.

Once you start trying to move heavy things about off road its easier to make them selfpropelled than trying to carry them. I’d love to have a drive of one of these but NZs export deals with Russia only resulted in us getting Ladas and Belarus tractors nothing on this scale.

You know what they say, it’s easier for a horse to pull a heavy load than to carry it.

I’ve read that this horse is the world’s largest truck-tractor, it’s a Nicolas Tractomas with a 1,000 hp Caterpillar, working in Australia. Total GVW of the whole rig is 535 tonnes.

Thats a road train the biggest one used on roads was 7 side tipping trailers, we are not permitted in NZ to tow more than 2 trailers there are many pieces of road you cannot remain on your side of the road towing more the corners are too tight.

At 3.5m wide it’s a bit more than a road train, it is a heavy-haulage rig, maximum speed is 50km/h. I’m not sure whether it just operates within the coal mine it is based at, but there aren’t any registration plates shown and it would need escort vehicles if it was taken on the public road.

I wondered if the 1934 AEC 8×8 road train that initiated the type in the Northern Territory was similarly oversize, but the specs say it was 2.3m wide. Quite a bit less powerful at 130hp!

Where do they use these for, given its long wheelbase ? I do see this Kenworth has a DAF cab.

I can just picture Dan Aykroyd and Chevy Chase in front of that big green one with the nuke.

Source-Programmable Guidance!

Spies Like Us!

I thought of the same thing too!

The USSR did try to find export markets even before the fall, I remember an article from an old Time magazine from the 70’s where they were importing Russian tractors into the US, don’t know how that turned out, and of course, we know about the Ladas in Canada and other places.

Actually, long, lo-o-ong before the fall; maybe since late 1940s or early 50s

Never seen these trucks personally; analogous KAMAZ 8x8s are quite common here in Russia, though.

Used to see the some of these, however (photo) – both in military and civilian disguise. And just a handfull of 12-by-12’s by another manufacturer, the BAZ – mostly autocranes. They are obviously far too large for city traffic.

They look like trucks you would use to survey another planet….

That thing is BADASS. Zombie apocalypse? No problem!

Robert, another great article completely out of the norm! Fascinating and well researched stuff as usual, thanks for sharing.

What a way to one-up the Unimog crew!