(first posted 5/8/2017) After WW2, Britain’s railways were forced together, and like all such combinations took their time to find their new style and identity. So it was 1951 before British Railways had a face it could call its own – but it wasn’t shy about it, and proudly gave it the name of Britannia herself.

Railway nationalisation was inevitable once the transformative Labour government of Clement Attlee swept to power in a landslide election win in 1945. Three of the four mainline companies – the London Midland and Scottish, the London and North Eastern and the Southern – were barely twenty five years old; the Great Western was over a hundred, but all were merged without sentiment into a new government controlled body, British Railways, on 1 January 1948. New Year whistling in stations, engine sheds and goods yards was even more enthusiastic than usual, as railway workers celebrated a long hoped for change, but on the ground and the rails little changed in the first few years.

The railways were in a poor state, after almost a decade of wartime overuse and under maintenance, and the locomotive fleet was no different, so there was a burst of activity to bring it up to scratch and to build more – but to the pre-nationalisation designs. Over 1,500 engines of existing designs from all four companies were built, right across the spectrum from branch line tanks to express Pacifics and heavy freight engines.

BR had entrusted locomotive development to Robin Riddles (1892-1983, seen above on a Britannia footplate); he was a 40 year veteran of the LMS, the largest of the old companies, and its predecessor the London and North Western. Previously William Stanier’s assistant, he had worked for the government’s War Department during the war, designing simple and robust freight engines for the UK and then continental war effort. He now had responsibility for a fleet of more than 20,000 disparate engines across Great Britain. Riddles understood the need to move on, both technologically and stylistically, from the past, and BR allowed him the time to get it right.

Among the old companies, the LMS had experimented with diesels; work on an electrified mainline linking Sheffield and Manchester, begun by the LNER, was nearing completion; and the Southern’s third rail electric units were slowly spreading. The Great Western even tried gas turbines. But there was no money for switching to new technologies, cheap domestic coal was abundant and imported oil was expensive – so steam would have to provide the next generation of power. Riddles set out to design a fleet of modern, standardised engines, covering the full range of uses, using modern features for easier operation and maintenance, and styled in a new coherent way.

The first to appear was an express passenger engine, numbered 70000.

70000 was completed at Crewe, the old LNWR works in Cheshire, 150 mile north of London, in January 1951. She ran for a month of proving trails in plain black, before being unveiled in express passenger lined Brunswick green at a naming ceremony at Marylebone Station, London, becoming Britannia.

Britannia was a Pacific – six coupled wheels, with a leading four wheel bogie and two trailing wheels under the cab – by then the standard for British express engines. But the rest of the design was not typical for a British express engine. Designed for ease of use and maintenance and to cope with poor quality coal, she had a simple two cylinder layout; none of Gresley’s and Stanier’s three and four cylinder pre-war complexities anymore. 70000 made do with two cylinders of 20in by 28in – the largest possible in Britain’s cramped loading gauge, with outside Walschaerts valve gear operating in full view of those at the lineside – a first for those watching British express trains. The boiler pressure was also standard – 250 lb per sq inch, but the boiler itself was based on the welded design used by Bulleid – the most successful of the innovations in the controversial Merchant Navy class – with added details such as a rocking firegrate and self-cleaning ashpan. These gave better steaming on poor coal, and reduced daily servicing work.

So, less power than an LMS Duchess or an LNER Peppercorn Pacific, with tractive effort of 32,000lb/ft – but also significantly lighter. This made the class perfect for the East Anglian mainlines from London Liverpool Street to Ipswich and Norwich, which couldn’t bear the weight of the largest locomotives and had thus had to make do with second string power – assigning the Britannias there was the first time the route had had state of the art power for half a century.

And she looked like no other British locomotive. The styling was deliberately modern, with a high running board exposing the whole of the driving wheels – a first for a British express engine. No more of the Great Western’s tradition or 1930s streamlining here! And none of Bulleid’s over ambitious leap forward – just thorough application of modern techniques and design to meet post war needs and resources. A proper cab and more exposed pipework than we normally saw completed the visual modernity of the design. And deliberately, no links to the looks of anything that had gone before. No wonder British railfans were aghast – to north American eyes, this may look like a smart, stylish engine; to British, it looked austere, functional and utilitarian, with the standard smoke deflectors completing the functionality of the design.

The name was perfect – Britannia is the personification of Britain, and symbol of her strength and history. The figure of Britannia has featured on British coins from the Roman era to the current £2 coin, and the name captures in one word the national unity despite diversity that post war Britain then manifested – how things change! It was selected by Riddles, who had to override the objections of the Locomotive Naming Committee (BR was now nationalised, obviously), who complained that an existing ex-LMS Jubilee 4-6-0 was already carrying it. But Riddles clearly knew the saying ‘one chance for a first impression’, and thankfully won the argument.

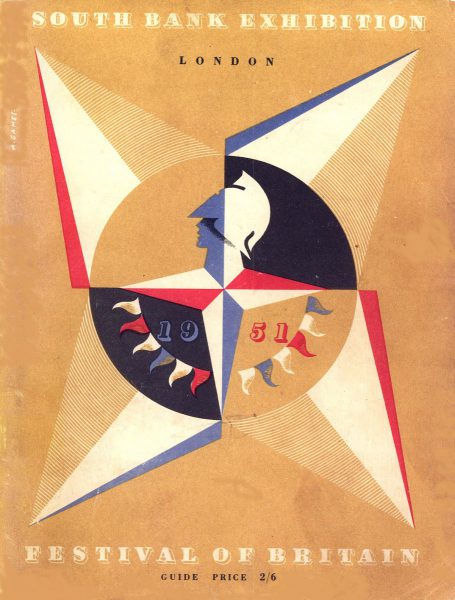

The timing was also perfect – 1951. The end of austerity and rationing was in sight; repairs to war damaged cities were well underway, and the boys had come home and got jobs. With hindsight, the decade of ‘never had it so good’ was beginning, and the Festival of Britain caught the mood with its promise of a high tech scientific future. Bang in the middle of this sat Britannia’s sister no 70004 William Shakespeare, in a special high gloss finish version of the nationalised company’s new green livery, and alongside, the new Woodhead route electric EM2 no 26020 – two proud promises of new progress.

Britannia had another moment of fame in 1952, when, with her cab roof specially painted white in a railway tradition for such occasions, she hauled King George VI’s funeral train from King’s Lynn, in Norfolk, to London.

By September 1954, there were 55 Britannias across Britain’s rails. 54 of them were named (for some reason, 70047 never was), and the names were mostly inspired choices too. We had great poets from all the cultures of Britain – Tennyson, Robert Burns, Geoffrey Chaucer, Rudyard Kipling; semi-mythical heroes – Boadicea, Alfred the Great, Robin Hood; royalty and rebels – Black Prince, Coeur-de-Lion (more commonly known as Richard the Lionheart), Owen Glendower and Oliver Cromwell; powerful Stars – Morning, Rising, Shooting, Polar; and, inevitably, some military heroes, including Iron Duke, a popular name for the Duke of Wellington and an old Great Western name. And, finally, a group based in Scotland recognising the great Firths (or estuaries) of Scotland, from the Solway in the south west to the Dornoch in the north and the Forth in the south east. Overall, a more imaginative and impressive set of names than most, such as the Great Western’s seemingly endless lists of country houses and the Southern’s class named after public schools (which, in Britain, is what we call expensive private schools, obviously).

The Britannias were based around the country. As well as the East Anglian expresses, they worked in Scotland; on the former Great Western; and in north west England. Initial shock at their appearance and dismay at the ending of the traditional designs of the old railways was soon replaced by admiration for their reliability and relative ease of use and maintenance, while engine crews and shed workers alike appreciated their modern design features.

By 1960, BR had built 999 standard class locomotives in 9 tender and 3 tank classes, ranging from power classification 2 in 2-6-0 and 2-6-2 tank versions to the mighty 9F 2-10-0 freight haulers – 1 in 4 of the BR standards were 9Fs. They all shared the family look pioneered by Britannia, in an impressive piece of modern design thinking, even if some (notably the class 5 4-6-0) were very closely based on LMS designs. The style also appeared on the rebuilt Bulleid Pacifics, from 1956.

But, by 1968, they were all gone, as BR banished steam rapidly once the decision to move to diesel was taken in 1955 and new power began to arrive in significant numbers from the early 1960s onwards.

Britannia herself worked East Anglian expresses until the coming of diesels usurped her in 1961. She moved to the old LMS, and was based in Crewe and then Manchester before withdrawal in 1966, after just 15 years’ service. She is now preserved by the Royal Scot Locomotive and General Trust, and after a long career on both the mainline and persevered line, requires an overhaul before she runs again.

Two other standard Pacifics deserve special mention. One is the one-off class 8 no 71000 Duke of Gloucester.

No 71000 was the only class 8 BR standard Pacific built, in 1954. Intended originally to be an enlarged Britannia, she ended up as a three cylinder locomotive – two were not enough for the power output Riddles wanted – with Caprotti rather than Walschaerts valve gear.

In BR service, she was a failure. Steaming was poor, as a result of a normal double chimney being fitted to cut costs rather than the Kylchap blastpipe Riddles had specified. As the BR Modernisation Plan was now in full flow, no effort was expended to put right this and other weaknesses, and the locomotive became an unpopular white elephant.

She did make it into preservation, and underwent restoration in the 1980s that corrected the design flaws and turned her into a free steaming and powerful locomotive.

The other is 70013 Oliver Cromwell, named for the Puritan landowner and MP who became the leader of the Parliamentary forces in the English Civil War and subsequently Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England (1653-58) – the first and so far only republican leader of England. Cromwell (1599-1658) didn’t just rebel against taxation without representation – he chopped the King’s head off. But, for CC, the significance dates from just 1968. Steam was ending on BR – and the very last steam hauled train was to be a return excursion from Liverpool to Manchester (very appropriate – the route of the first railway in the world designed from the start to serve passengers as well as goods), then, with a change of power, on to Carlisle over the famed Settle and Carlisle line, and return. All for just 15 guineas return – £15 15 shillings, or £15.75 in the post 1971 decimal currency.

Manchester Victoria, 11 August 1968

And BR seriously expected that that would be that – that never again would steam run on the mainline. The engine chosen for the Manchester – Carlisle leg was Oliver Cromwell – in February 1967, the last Pacific to receive a general overhaul, at Crewe, after a 125 years of steam locomotive construction and repair there, and the last Pacific to haul a scheduled passenger train (until 2017). That earned her a place in the National Collection, and she is now based on the preserved Great Central Railway in Leicestershire, where she regularly works on the only preserved double track mainline in Britain.

And, finally, there was another Britannia – one of BR’s class 87 5,000 hp 25kv AC electrics built in 1974 for the West Coast Main Line.

It now works in Bulgaria, nameless. Not quite the same!

I love your pieces on locomotives, BP! It is funny how quickly things turned against steam power there in England, particularly as new as these were when they were decommissioned.

I’m not the biggest train guy out there, but watching one of those old steam locos get underway is great thrill.

Problem was that immediately after the war, there was no alternative but to continue with steam. But once the decision had been made to end steam, it all had to end pretty quickly, as it would have been uneconomical and impractical to run two motive systems alongside each other for any longer than was absolutely necessary.

Meanwhile, the railway had to be kept going, which is why the last, massive 8F steam locomotives weren’t completed until 1960, with the final steam service running only eight years later.

The uneconomical impracticality of Britain’s post-war railway system is another matter, but for those in the know I’ll just say “Tees marshalling yard” and leave it at that.

I’d be very happy to pay for a book of BP’s railway pieces!

Tees and others!

Thanks for the kind words, but I’m not charging! Just click on a few adverts to generate some support for the site! ?

+1

Electrification was seen as the way ahead in the longer term, but as Britain had (and still has) large reserves of coal, new, easier to maintain steam locomotives were regarded as sensible option for non-electrified lines, particularly since they were considerably cheaper to build than diesels and there were already plenty of works and experience available to build them. In those days nearly all electricity was generated by burning coal so electric and steam locos effectively were using the same indigenous fuel rather than imported oil (no North Sea oil production in those days!).

Outside the railways though the workplace was changing rapidly through the 1950s with the growth of new, modern industries bringing with them improved working conditions. It took a while before the overall slack in the economy was taken up post-War, but by the middle to late ’50s, with rising wages and expectations it was becoming increasingly hard to recruit the army of fitters, cleaners, firemen and drivers these labour intensive steam locomotives required. They were also increasingly seen as dirty and old-fashioned. While electrification could have presented a modern face to the railway, as it did in post-War France, the snail’s pace spread of electrification in the UK lead to the railways as a whole being regarded as passé. In the end Britain rushed into mainline dieselisation late, Since the last BR standards were built in 1960 many went to the scrapyard after less than a decade’s work.

Apologies to Philip above for some duplication – for some reason his reply didn’t show when started to write this.

No problem. The public’s perception of steam went from “cutting edge” (A4s etc) to “hopelessly outmoded” in under twenty years, with a world war in the middle!

Very well written and enjoyable series.

+1

I see some Southern Pacific ‘Daylight’ influence in it.

Great read and some wonderful videos. The cost of £15.75 for the last steam train excursion in 1968 would have been an astronomical amount of money back then; probably a whole week’s wages for the average working man. Your comment about the white topped King George VI’s funeral train reminds me of a story told in Punch magazine back in the 60s. It was common to tart up and whitewash the railway stations that the Queen might pass whilst on-board her private train on her annual trips up to her castle in Scotland. Apparently, this included the stocks of coal stored on the rail side and in the fuelling yards. “Aye”, said one rail worker to the reporter; “and if you stand around long enough, you’ll get painted too”

Great read. It’s only 8:38 am but I suspect that will be the high point of Tuesday. Thanks

I always look forward to reading your locomotive stories, Very instructive and fun to read, Thanks!

Another great article by Big Paws. I am left with a few questions though. Although they had been used on American steam locomotives for 20 years prior why were Boxpox, Scullin or Disk drivers not used on driving wheels on British locomotives? I would assume they had superheaters but did they have front end throttles or cross balanced drivers? And why only 250lbs boiler pressure when most new mainline engines in the US were built with 280-300lbs starting at least 15 years before? All of these plus cast locomotive frames with cast integral cylinders and all ancillary equipment had been proved to increase power and reduce running and MOW costs(esp hammer blow) in the US.