(First posted 7/22/2014) When pictures of this Citroen CX were uploaded to the cohort by Triborough some weeks ago, I noticed them immediately but let them sit. This is one of those cars whose charms destroy any ability I have to approach a summary objectively or rationally. Having never experienced a big Citroen first hand only reinforces its mystique, allowing me to pretend the car’s uncommon virtues outweigh its glaring shortcomings. An additional hurdle presents itself in dodging cliches frequently used when describing the cars. It all conspires to make writing about the CX somewhat of a challenge.

With other pictures of ’70s Citroens popping up in the Cohort along with Roger’s summary of the incomparable DS, the CX begged to be given some attention. While the DS that it replaced is a nostalgic vision of the future that tugs on one’s heartstrings, the CX is more an exquisite expression of contemporary sensibilities in its day. Rather than looking like a 1950s sci-fi relic, the CX was a design mere earthlings could relate to; its uniqueness was a matter of being fashion forward, subtly detailed and beautifully proportioned, not necessarily imaginative. It simply is one of the cleanest, most compelling sedan shapes put into production and imparts a sense of capacity in addition to mere efficiency; a real jet-age express.

Despite wider, more international appeal than the DS, dig under the skin and there were real compromises which we’ll address later. In line with that, life was not easy for this last of the “real” Citroens. Hatched before the acquisition by Peugeot in 1974, it was introduced the same year with big shoes to fill, and a very wide array of competitors depending on how it was equipped. Citroen was expected to reinvent the wheel, or at least took it upon themselves to fulfill that responsibility, but the car it was replacing was so far ahead of its time, it was difficult to know where to begin.

Any such dilemma was hard to notice judging by outside appearances, as the CX was a clean break from its predecessor stylistically. Following hot on the heels of 1970’s SM and GS, the CX would be the third Citroen formed in the kammback mold, as well as the third of the company’s cars styled under Robert Opron, who was hired by Citroen after outgoing design chief Flaminio Bertoni roiled him during a job interview in dramatic fashion. Opron’s first job at Citroen was the facelift of the DS’s nose in 1967, in which he gave that car its famous swiveling headlights covered under a glass canopy. He was seemingly given free reign at the firm until being unceremoniously fired upon the Peugeot takeover; his later efforts (Renault 25, Renault 9/11) are nowhere near as pure or dramatic, though the Fuego and Alpine A310 bear his unmistakable influence.

The Citroen CX and its little brother, the GS, wear a shape similar to that of Pininfarina’s BMC 1800 concept car. Whether this was the result of direct influence or coincidence is unclear, but the later Rover SD1 would more obviously share its lines. Fuel crisis or otherwise, aerodynamics were becoming a design priority for many manufacturers (though some would continue to ignore such considerations for another decade or so); in this sense, the CX, named for the coefficient of drag abbreviation, didn’t necessarily represent a major improvement over the DS’s excellent-for-1955 figure of .37, but it certainly looked sleeker. Certain details, like the window frames and bumpers leave no doubts as to the CX’s age and there’s no mistaking it for anything recent, but with its more integrated detailing, it’s aged better than the older DS.

Despite refining the car’s style to widen its audience, retaining the DS’s iconic dynamic qualities was Citroen’s priority. The amazing Hydropneumatic suspension therefore remained an integral part of the experience. And if anything, the floating on air sensation it created was augmented by a new power steering system called Direction à rappel asservi or DIRAVI, first seen on the SM. If proof of the jet-age spirit which gave birth to the car is needed, the best evidence is the joystick steering control Citroen was experimenting with while the system was being developed. Realizing that most drivers probably didn’t want to steer by joystick, the concept was refined via use of a steering wheel, but it’s best to think of it as a switch rather than an actual connection to the steering mechanism (there was a real connection but it was only in use in the event of hydraulic failure).

Basically, high pressure hydraulics would force the steering dead ahead at all times until the steering wheel was turned. When that happened, hydraulic force–increasing with greater application of lock–would be apportioned to whichever end the steering rack (right or left) corresponded with the direction in which the driver turned. At about 2.0-2.5 turns lock to lock, it had a direct ratio which would have been impractical with traditional, hydraulically assisted steering (DIRAVI was hydraulically activated).

By decoupling the steering wheel from the front wheels, and by making it such that only input from the hydraulic system could turn the wheel (and not forces acting on the front wheels from such things as potholes, ruts, blowouts, or unequal road-surface friction) the high-pressure system was able to completely isolate the driver from steering kickback and diversion from their intended course. Even more impressively, because the hydraulic pressure acting on the system would increase with speed, the steering became very stiff on the highway, making straightline tracking even more steady and secure than would be possible with an unassisted set up.

In addition, because the system was designed to keep the steering wheel dead ahead, it would always (and rapidly) return to center once driver input ceased. This would catch new drivers off-guard, since it meant that one couldn’t always allow the wheel to return to center on its own, as it could occur too rapidly. Combined with the very fast ratio, along with the brakes which operated through a giant, pressure-sensitive, floor-mounted rubber pad controlling a valve with less than one-inch of travel (in place of a regular pedal), it provoked very jerky, swerving maneuvers from drivers unaccustomed to the car. No doubt, many people didn’t understand the appeal of a car which had to rise off its haunches in order to move, all while greeting bystanders with a series of loud hisses. But to those who could wrap their brain around it for a few days, the experience was said to be effortless and rewarding.

It would appear Citroen aimed for an almost aeronautical driving experience, whereby one could guide the car almost by whim using the slightest flicks of the wrist and ankle. Surely, the new steering system was in keeping with the brakes which operated in a similarly sensitive fashion, and matched well with the suspension’s indifference to major pavement imperfections. Such a shame, then, the final component to the CX experience–a rotary engine–never panned out.

As the front-drive Traction Avant and DS were state of the art in their day, Citroen, keen on maintaining its leading edge, designed the CX around a transverse engine layout. That would make the CX the first large car to adopt such a layout, helping continue the company’s reputation as a purveyor of all things new, in addition to saving eight inches in length versus the DS. We scoff at large, traverse-engined cars today, but with its hydropneumatic suspension making up for imbalances, tuning the chassis for a good ride was much easier and in a market which sold large cars with small engines by the handful, the advantage of rear-wheel drive was often minimal. As it turned out, finding an engine to suitably tax the front-drive chassis proved elusive.

The DS went without a suitably strong powerplant for most of its life, with flat-sixes (among other solutions) being canned as too heavy, complex or expensive. With the compact, smooth-running rotary engine as the crown jewel to Citroen’s achievement, the aerodynamic and space-efficient CX would glide over bumps, quickly whisking its unstressed driver and his occupants to their destinations free of fatigue. Other cars, with their coil-sprung suspensions, rattly engines and slow steering ratios, would surely be primitive by comparison. Unfortunately, things turned out differently.

Citroen had taken a cautious approach to developing and introducing their Wankel engine, codeveloping it with NSU and engaging in real-world beta testing with specially fitted, limited production Ami-based coupes. But reliability issues, not to mention exhaust emissions and fuel consumption, were impossible to adequately sort out. Warranty costs incurred by the NSU Ro80 were deterrent enough, but the cost of developing the rotary project and the new CX bankrupted Citroen during the year of the fuel crisis (an enormous additional problem). The three-rotor engine planned for the CX was therefore scrapped, leaving the big car with a tiny engine bay. At this point, there was nothing to do but adapt the DS’s engine for transverse placement in the CX, leaving Citroen’s plans for vibration-free transport in the shaky hands of large-displacement, pushrod fours.

The car was nevertheless introduced to the public with decent initial success, despite a lack of approval for US sales and no automatic transmission available. It didn’t shock the public like the DS had, but managed to expand Citroen’s draw to a broader base of consumers.

Engines on hand at launch were two carbureted units of 1985 and 2175 cc, respectively, allied to a four-speed manual. At this point, the DS was available with fuel-injected 2.3 liter engines and five-speed transmissions, though until it finally went out of production in 1976, it was nominally upmarket of the new car. A major change over outgoing DS was the introduction of diesel engines. Initially in 1976, a 2.2 liter unit was offered, with a 2.5 liter, 75-horsepower unit joining in 1978 (a competitive figure for a naturally-aspirated, indirect injection diesel).

By 1978, a fuel-injected 2.4 and a five-speed were also made available, along with a three-speed semi-automatic “C-Matic,” with both a torque converter and clutch activated by the gear lever, similar in principle to the unit seen on the NSU Ro80 (presumably what Citroen had in mind to be paired to the three-rotor Wankel engine). The CX’s powertrain was slowly beginning to claw back some degree of effortlessness needed to match its chassis.

Our New York City-based feature car, as evidenced by the side marker lights, is a grey model import. Its chrome trim and steel bumpers highlight it as one of the earlier cars, but its rust-free condition lead me to suspect it is at least a 1981 model (rust proofing was inconsequential before these years).

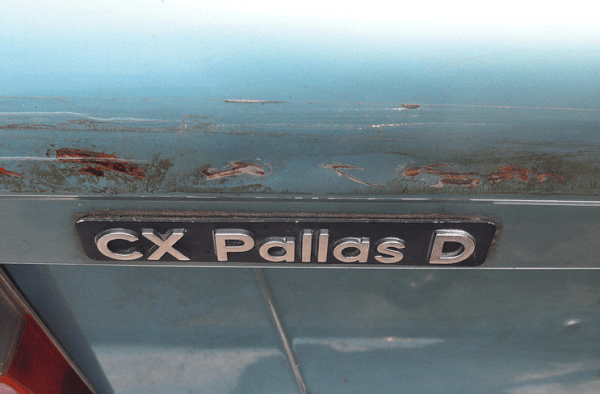

As front wheel arches became more pronounced by 1982, this car is likely an ’81. That this is a diesel-engined variant (as indicated by this badge) also helps narrow it down since it would have likely been imported during the height of the great American diesel boom (diesels were also easier to get past the EPA at the time) which began dying out after about 1983.

An indirect-injection, naturally aspirated diesel engine may not cut in New York these days (or any densely populated area), but with its unmatched suspension design, in some ways this now-beater would be perfect on the city’s battered streets. This is no-doubt a tough car to operate in such an environment, but lest you think it’s because the unibody is too fragile, the CX was unique in that it incorporated front and rear subframes which were actually connected with long, flat rails.

Given the condition of the Big Apple’s streets, this design feature must aid in secure use of this nearly thirty-five-year-old car today, but it was likely conceived as a way to engineer larger load-carrying variants without having to excessively beef up the structure of the car. Indeed, this Pallas (that’s Greek for Brougham) model isn’t actually top-of-the-line; Prestige models used a ten-inch longer wheelbase, shared with station wagon versions, which vie with Peugeot’s and Volvo’s rear-drivers as the world’s best long roof cars. Many were converted for hauling duty and the CX served as BBC’s car of choice for rolling shots; its dual role as both a beast of burden and a convincing luxury sedan are unique in a front-driver.

Carrying all that weight and prestige wouldn’t do with the merely adequate engines and semi-automatic transmissions. A fully-automatic transmission came in 1981, a 2.5 liter turbodiesel (fastest diesel sedan in the world at the time) and a turbocharged gasoline 2.5 liter came in 1984; intercooled versions of both soon followed. Though the automatic and turbo engines were never offered together, the CX finally came close to having the powertrains it deserved.

There were other engines added, including all-aluminum overhead cam units, but there are simply too many variations of the car to be covered here. Suffice it to say, 2.5 liter turbocharged engines got to the to point of making the CX genuinely fast for its day, but interest in the car had long begun to wane. Peak sales of 132,675 were achieved in 1978 and by the time engine choices were sorted out, news of the car’s fragility scared buyers away, while competition in the form mechanically conventional cars like the Audi C3-series 100/200/5000, the Mercedes W124 and even the Ford Sierra appropriated just enough of the Citroen’s avant-garde thunder to woo style-conscious buyers. By the late ’80s, a revised interior, more sophisticated electronics, improvements in quality and ABS would combine with enhanced performance to create a highly desirable executive car for those who could tolerate the more dated aspects of its ergonomics and overall operation, but it would be slow-going until the final Familiale (that’s wagon to you and me) rolled off the line in 1991.

Not surprisingly, the car’s biggest export market was Germany where, if stereotypes have any basis in truth, its unique engineering was appreciated by buyers. Over the sixteen years the car was in production, 1.2 million were sold overall, but in addition to all the amazing qualities the CX represents, it also signifies the forfeiture of the luxury car market by the French to the Germans. With unfavorable circumstances forcing Citroen and Chrysler Europe into Peugeot’s overextended embrace, the newly formed PSA fielded multiple luxury cars which competed with each other for development money and market share. But for all the negativity surrounding the automaker’s efforts in the luxury car field, the CX’s continued development over many years of declining sales, along with the continuation of its technology into its successor, shows genuine good faith on the part of Peugeot management.

As much as many like to characterize the CX and large Citroens as uniquely French, it would require a fair degree of intimacy with the country to know what that really means. If we want to drag out the old French-car cliches, let’s at least try and put the car into its home country’s historical context. We can see the car roughly coincided with the debut of the Concorde, the TGV and an unparalleled commitment to nuclear power. All were impressive achievements in the late post-war climate which seem to be either failed or flagging prospects today (even the TGV is in a slight slump), so rather than merely attributing the CX’s character to a question of national origin, one can view the car (along with those other projects) as an embodiment of French modernism in a post-modern era.

There was simply too much optimism and good faith involved in the car’s creation to sustain it in a disillusioned world; it’s sad when you think Citroen built an entirely new factory in which to assemble it. One look at the social problems currently facing France reflects this idea more poignantly (though it would seem that outside of Germany, current home of the luxury car, this is the default situation across Europe). Whether or not one views the CX as uniquely Gallic, there is a fascinating parallel between the car’s trajectory and its birth country’s recent history (then again, the same could be said of many ambitious British and Italian carmakers’s efforts).

What dates the CX the most, oddly enough, is the society which has changed around it. Cars like competing Mercedes and BMWs may have confounded some with their enormous steering wheels and tail-happy behavior, but they didn’t require their owners to re-learn how to drive. And as the ’80s wore on, those interested in turbo power and uniqueness had a variety of Saabs to choose from, but even those very rationally conceived cars were eventually deemed too left-field to be desirable. Image and status are as important as they ever were but it seems that these days, people stick with what they know, whether it’s yet another remake at the theaters or a German luxury sedan whose basic shape hasn’t changed in decades. Compelling arguments can be proffered as to why this is the case, but as a car designed for those who lust after novelty, the Citroen CX has no place in today’s world.

Related reading:

Car Show Classic: 1985 Citroen CX 25 GTi Series 2 – Blue Is A Warmer Color Than Grey

Curbside Classic: Citroën ID – The Goddess Storms The Bastille Of Convention

Curbside Classic: 1972 Citroen SM – Gran Touring, Franco-Italian Style

Cohort Classic: Citroën GS – One For The Anoraks

Cohort Classic: Citroën XM – Its Three Predecessors Were Hard Acts to Follow

Excellent article on an excellent car.

If you desire one, I’d Always go for the later Series 2 Cx’es, with the plastic Tupperware bumpers, a much much more matured Cx, much less rust prone and less electrical problems.

of course you’d miss the binnacles with the cyclops, the button arrangements for lights, wipers and indicators but the built quality and engines have been seriously improved.

For me I Always prefer the 2500 TRD, the 2.5 liter Turbo Diesels, they fit best with the Cx’es relaxed character.

‘Re-learn how to drive’. Very pithy, Perry. I read a review of a Mini variant (IIRC) recently where the reviewer was amazed to find a clutch pedal. Cars advertised on TV as being able to park themselves. We even have a public service advertising campaign here in Victoria, Oz, telling new car buyers to make sure their car has automatic safety braking. It’s all pointing to cars that drive themselves, requiring less and less of the driver. It reminds me of that scene in ‘The Right Stuff’ where the astronauts demand a window in their capsule. You’re right about the changes in society and what the average punter expects from their personal transport. Relearning how to drive is the last thing the consumer wants.

As to the shape, I dropped a love letter when Edward posted his CX story a while back. It’s better than the DS, but that is of course debatable. At the moment the prevailing style is three box saloons, but I don’t think that’s permanent. Maybe, fingers crossed, people will get tired of same-same and demand shapes as different as this again.

What a great week it’s been for euroxotics on CC. Yay!

Perry,

You’re absolutely right to spot that that left field so often makes sense but is rarely confirmed through commercial success.

This was a great car, and you’ve shown it was holistically conceived, but still the ultimate winner was the conventionally engineered (but well engineered) German car.

And the world is therefore a less interesting place

FYI

The third nose the DS’es ‘shark nose’ with the four headlights and many other goodies like hight adjustable seats and the later doorlevers on the DS series were actually stolen from tne discontinued Panhard BT24 and Ct24 cars.

Production of thes cars discontinued shortly before the third series Ds appeared.

Louis Bionnier (inhis early eighties I believe) was responsible for the design of the 24 Panhard series, which on its turn was heavily influenced on the Chevrolet Corvair, especially the floating roof.

I think that there might be another issue. It is one thing to bring out a cutting edge design that looks like nothing else on the road. It is quite another to try and sell it for 16 years. I think you can get away with that if you start with a relatively conservative design. It becomes timeless. However, when something starts out as stylish and fashionable, it eventually become a reminder of last season’s fads.

MB, BMW and Volvo could wring many years out of a style. Others like Citroën and Saab went stale long before their makers could afford replacements.

I will confess that these don’t do much for me, but then I am not a huge fan of that stark, cold modernistic style that was so popular into the early 70s.

Fair point, but both the Traction Avant and the DS sustained very long lives, partly out of popularity. Expecting the same of the CX might have been legacy conditioning.

André Citroën, although long departed (and deceased) believed the ideal approach for a production car was to develop something so advanced that it could be sold for many years with only minor evolutionary changes. Remarkably, the Michelin-owned management that succeeded him continued that philosophy with a will.

…apparently, lessening the need for regular, and expensive, major changes to be made to a car is economical.

I dunno how true that is, but it probably made sense in a different time and place.

It makes reasonable sense from a financial perspective, as long as you don’t make the BMC mistake of making the product so expensive to build that you never make any money on it even after the initial development and tooling costs are paid off. The number of older designs that have lingered on for years or even decades on basically the same tooling is evidence enough of the principle, although I don’t think too many of those models were consciously intended to last 15+ years as a deliberate business strategy.

Its a gamble. History is strewn with advanced looking vehicles rejected by the public.

Having said that, the CX was much closer to the DS than the DS was to the Traction Avant.

1955-2007 Citroens came with the clever hydraulic suspension, the later versions are computer controlled called hydra-active and it works very well,the active Xantia that beat all comers in the moose test is the first effort my daily drive has the final refinement of it same as fitted to the C6, New Zealand has terrible roads but youd never know driving a Citroen

Citroen does suspension better than anyone else that technology was absorbed by Peugeot who make their own shockabsorbers, Peugeots ride very well too.

The DS still looks somehow timeless, as though it belongs to an alternative universe and somehow ended up here by mistake.

The CX somehow seems much more “normal” in its styling, and as such seems dated now. Wonderfully appealing, but dated.

For the XM that replaced it I have but one word: ugh!

I’m not sure I agree. The gen2 Prius looked pretty far ahead of its time in the US in 2004, but now many cars look very much like it. And the CX had the same basic shape. If Citroen had just kept making it, it would eventually have looked mainstream, even conservative. 🙂

Famous owner Carlos Santana. i guess he was growing his hair long again in the late ’70’s.

I recall the contemporary magazines were loving these.

A wonderful write-up on a car that I really wish had come to American thru normal channels. What I especially found interesting is the development of the car in light of what else France was doing technologically at the time, as well as what the neighboring countries were attempting.

Allow me to add one more comparison:

While this car was being developed, Detroit was giving its customers broughams. And, to me, that says it most of all.

If my memory serves me right, the American legislation was adapted to block the CX from entering the United States, something to do with variable ride hight and headlights

Because Citroën where really aiming to challenge the US market back then.

Someone posted a great pic of the prototype CX nose/bumper for the US on the recent GS story

Therein lies one of the main reasons Reagan got swept into office in 1980. Not just the Iran hostage crisis, which exposed the plodding nature of the Carter administration, but the out-of-control regulation that strangled many industries, not just automotive. That was scaled back considerably after 1980.

The problem with the safety movement in the 1960’s and 1970’s was that it had a “my way or the highway” philosophy that mirrored its founder, Ralph Nader. A lot of positive things were achieved, but you also got the starter interlock for seat belts, 85-mph speedometers, the 55-mph national speed limit and the rise of enforcement for revenue, 5-mph bumpers, headlight laws stuck in 1940, etc.

Some of the safest cars ever built till then, like Volvos and Mercedes, had to remove safety equipment to comply with US regulations. Citroens were out because of dumb bumper-height regulations, and MG’s were ruined. To this day a lot of innovations available in Europe don’t make it over because of them, not to mention the litigious nature of the US legal system.

In the spirit of beating down the big bad auto industry, you got a lot of stupid regulations. You also got a lot of half-assed workarounds from the industry. But it isn’t called the Malaise Era for nothing.

While this attractive and practical car was made we were churning out abominations like the Allegro and the slightly less horrible Maxi and wedge shaped Princess.There was another dose of the same old medicine at Chrysler UK as the Arrow cars carried on as before.The Ford Cortina and Vauxhall Victor were still big sellers and were left alone til it was time for the Mk4 Cortina and the Vauxhall Cavalier(Opel in drag) came along

You guys were trying with the SD1, but too little too late. Many, many reasons for the downfall of the UK motor industry, but if the Pininfarina Aerodynamica saloons had been used, would it have been enough?

Probably not as more than likely they’d be stuck with the same tired engine designs,not enough money for R & D and rushed into production before it’s faults were ironed out.Throw in BL’s shoddy build quality and history of strikes meaning a long waiting list and there’s a good chance of yet another dud

I’m trying to imagine a Hydrolastic-suspended Aerodynamica with a B-series under the bonnet. Sounds good to me!

But BL quality…..

I expect BL’s craptastic mechanicals and abysmal quality would have dragged down even the most brilliant design.

“While this car was being developed, Detroit was giving its customers broughams. And, to me, that says it most of all.”

Ultimately, the two weren’t that far apart. Both concepts catered to those who wanted a quiet, effortless ride.

Some developed technically complex and expensive – even for the vehicle*s owner – solutions.

Others used relatively simple and inexpensive means, such as well-padded interiors, the generous use of sound-absorbing materials and appropriate suspension tuning.

Decide for yourself which is more sensible.

Oh yes, before I forget: Some drove their companies into the ground, while others raked in substantial profits for years.

As I said: Decide for yourself.

Very interesting reading Perry. You have to admire Citroen’s willingness or even compulsion to innovate,although when the CX was underway surely the evidence must have been there to demonstrate it was unwise to push too quickly. I imagine the learning curve for the controls would have been fairly short and that there could be some rather vivid demonstrations of their dynamics! It is a shame the drivetrain was not up to the standard of the rest of the car, let alone adding this to the list of cars where the first choice of engine evaporated during development. I’m thinking of things like the Mini, Rover P6 and AMC Pacer.

Nice article, Perry. I am currently in the south of France and due to the CC effect not half an hour ago saw a very nice example of a CX Break (wagon) parked, alas I was not in a position to stop and shoot it. Aargh.

Amazing interior on these.

The rear seat in that factory photo does have an executive jet quality. I’d add this to a bucket list of cars to drive. Great write up!

Perry,

Insightful commentary on the CX and its place in history, including its eventual defeat at the hands of the German brands. It is interesting to contrast Citroen’s struggles with those of Cadillac – each aimed for a prestigious and ultra-comfortable driver experience in a completely distinct way, reflecting conditions that were both national and corporate, and each lost to the Mercedes/BMW juggernaut that established the template for today’s luxury car.

I would like to comment on your concluding statement:

“[A]s a car designed for those who lust after novelty, the Citroen CX has no place in today’s world.”

This sentence and the photo immediately below it, with its profile shot of a CX, make me think that you are partially correct. The differences that Citroen emphasized in the CX — its unusual and effective suspension, steering, and braking systems — the marketplace has indeed stated have no place in today’s world. They were answers to questions that only Citroen was asking. On the other hand, the distinct resemblance between the shapes of the CX and Toyota Prius, which the side view makes apparent, makes me think that maybe the problem was that Citroen was emphasizing the wrong areas in which to innovate. Outdated, unimpressive powerplants are a bad starting point for any car. If Citroen had successfully developed its rotary engine or some other engine with smoothness and power to match the other dynamic qualities of the CX, its story may have worked out quite differently.

(As an aside, is the resemblance between the shapes of the CX and Prius merely the result of convergent evolution from designing for aerodynamics and space utilization, or did Toyota’s designers have a photo of a CX on the wall, as an example of an avant-garde design, while at their drawing boards?)

As an experiment, it would be interesting to replace a CX’s hoary old pushrod four with a silent, vibration-free electric drive, say out of a Chevrolet Volt. That kind of seamless power delivery would probably completely transform perceptions of the rest of the car and its exceptionally smooth driving dynamics. Of course, no one would bother to try this experiment.

I disagree about the CX’s powertrains, but only because sales dropped as suitably powerful options became available. Otherwise, I agree fully. And in terms of novel experiences behind the wheel today, cars like the Tesla, Volt, and even Prius have something to offer.

It’ll be interesting to see how cars change and adapt over the next ten, twenty and thirty years. My own preferences tend toward very light cars with small, high-revving engines, but the part of me which likes big softies sees something to look forward to with electrics (provided they get the ride to match the silent powertrain).

A difference between these cars and the Citroen, however, is that the former have the aim of extending the era of the car where as the latter (along with the DS) was conceived as a testament to the car’s magic and unlimited potential and seems a lot less like an excuse for its continued existence.

It’s difficult to design a highly aerodynamic car without it ending up looking like the Pininfarina BMC Aerodynamica, which of course influenced a raft of cars like the CX and Prius and others. And we can see how increasingly many new cars are morphing towards that shape. It’s not a matter of avant garde, it’s just the laws of physics along with certain practical considerations, which eliminated the long tails of the 30s with the more practical but almost equally effective Kamm tail..

IMO you don’t necessary have to go electric to have a “silent, vibration-free drive” and “seamless power delivery”. A modern turbocharged petrol engine might do the trick, together with some good sound insulation. Speaking from experience with a 1.4-liter Volkswagen engine (with a supercharger and a turbocharger), there is practically no vibration and very little noise – when engine is idling, you practically can’t tell whether it’s running or not unless you check the rpm gauge. Because of supercharger and turbocharger, it has plenty of low-rpm torque and is overall very silent, you only begin to really notice the engine noise around 3000 rpm and you rarely need to rev it that much, most of the time you can keep it 1500-2000 rpm and 2500+ on the motorway.

There are other European manufacturers offering similar turbocharged engines (including the PSA of which Citroën is part) and I imagine they could offer similar benefits…

PSA went with twin turbocharging on diesels they are very good Ford fits those engines to their Rangers now 4 and V6.

I think the dilemma for Citroën in that regard was not that there is no place for novelty, but that novelty alone was not necessarily a strong selling point.

Various Citroën innovations were neat, but, particularly by the ’70s, required too much driver adjustment relative to the benefits. DIRAVI is perhaps a case in point; plenty of quite ordinary American cars had fingertip-light power steering with near-total isolation from road shocks without the twitchiness or odd self-centering action, and by the early ’70s Detroit was learning how to retain the ease without giving up some sense of straight ahead. Similarly, by the ’70s, there were conventionally suspended cars that offered a plush ride with handling composure, the Jaguar XJ being a leading example.

Buyers tend to be much more accommodating of quirkiness if it provides some obvious benefit. Look at the success of automatic transmission versus semi-automatic shifting, for example. Buyers never much cared for the latter, quickly sizing it up as different but not better, but people happily paid a premium for fully automatic transmissions and accepted their obvious price and performance limitations so they didn’t have to shift or use a clutch. People didn’t buy automatic because it was novel (the enthusiast crowd that likes technical novelty turned up their noses and in some cases still do), but rather because it was convenient.

It’s important to draw a line here between “novelty” and “eccentricity”…

“…plenty of quite ordinary American cars had fingertip-light power steering with near-total isolation from road shocks without the twitchiness or odd self-centering action, and by the early ’70s Detroit was learning how to retain the ease without giving up some sense of straight ahead. Similarly, by the ’70s, there were conventionally suspended cars that offered a plush ride with handling composure, the Jaguar XJ being a leading example.”

Outstanding point about steering systems in the 1970s.

The only difference is, Citroen’s steering was incredibly responsive and accurate. Detroit’s steering was not. There’s no similarity at all in the experience of driving those vehicles.

Having spent enough miles behind the wheel of Detroit cars of the early to mid ’70’s and also behind the wheel of a DS and SM (with DIRAVI), the difference in steering could not have been more radical.

To me, it wasn’t primarily about lightness or even the centering, but the absolutely fast, direct yet silky smooth connection to the wheels. Of course, road feedback was artificial with DIRAVI, but for some reason, in practice the Cit’s suspension and steering never left me dangerously ignorant of the road surfaces. To drive a DS, SM, (and a CX in the area occasionally- we had a Citroen dealer that eventually picked up CXA) for any length of time puts you back into conventional cars with the distinct feeling that the steering wheel is connected to the front wheels with a series of rubber bands. It really is that different.

As far as I can tell, North American car buyers just don’t like to have that much control over a car. 🙂

That interior in general looks like a fantastic place to spend time. An “executive car” in the truest sense? And I’ve always loved the styling of these as well; though hen’s teeth in the USA due to the import situation they were very visible in media and publications in the 80’s. I remember I had a yellow diecast of one, somewhere in the vicinity of 1:64–perhaps a yatming or similar. Matchbox made a CX break but I didn’t have that one until I bought it on eBay as an adult! Such a clean, modern shape and so unlike anything we ever had in the official US market. I’d love to even see one “in the metal”.

What a very cool car indeed even with the battle scars. Perhaps a truck backed into the hatch and caused the rust, that’s how my mother’s Dart got totaled twice. At first I thought this photo was from Tompkins County since their first batch of the Gold and Blue Empire plates were the FAX-series.

It’s a trunklid, not a hatch… and they (along with sunroofs) were always the first area to rust, at least in Series 2 cars like the CX25 GTi I used to own.

Thanks for doing the CX justice, Perry. Not an easy task.

…but a fun one! Anyone got a Lancia Gamma lyin’ around?

THAT would make a fantastic CC piece!

Ahh, that brings back memories from my time in Germany. My first car was a ’79 CX Pallas. Bonus car guy points for the 5-speed and metallic brown color, but no diesel.

I really want to get another one, even 20+ years later, but the thought of maintaining it properly in the US is pretty scary. I couldn’t afford proper maintenance on mine when I was 18, so I learned a lot about some of the weirdness of this car the hard way. I was raised to be pretty handy with car repair and maintenance, but this was more than I could handle at the time.

Things like oil and air filter changes were really difficult. There wasn’t a lot of room under the hood, since it was designed for a much smaller engine, so getting to these things was a challenge. They also had the spare tire under the hood with the motor, so that was even less room to work.

I also learned how hard it is to push-start a CX after it’s been sitting for a few days and the suspension has relaxed. The car almost rests on the ground until the hydraulics charge back up, so there’s lots of grinding underneath, and that much more effort. And yes, the steering is incredibly difficult when the motor isn’t running. Good times, right?

But when it was running, it was awesome. It took about a day to get used to driving it – not a huge effort to re-learn, and it made sense once I understood what was going on with the brakes and steering. Driving on cobblestone streets felt like smooth pavement. The seats were amazingly comfortable, especially for long trips. The car just chewed up miles (ok, kilometers) on the autobahn at 100 MPH all day. Despite the 2.4 4-cylinder, it was plenty fast enough in town and on the highway. Even got away in a police chase one time, but I did have a really good head start.

And I loved the bathroom scale gauges, single windshield wiper, weird turn signal switch (not self-canceling), the in-car oil gauge, spherical pod ashtray on top of the dash, and the weird spine-like trim that went down the middle of the headliner.

I’ve owned 25 cars and driven dozens more, and just for pure coolness and comfort, nothing else has been as good. I think they’re beautiful, and prefer the CX design over the DS – I think it’s aged a bit better. And I fear I’m talking myself into another one.

Thanks for the account; you’re not the 1st who’s raved over its ride quality.I feel like Tantalus here, seeing something I can never own, or even sample, at least without a tremendous amount of trouble.

Anyone know how well the current C5 with Hydractive 3 stacks up? I understand they reverted to more conventional brakes.

The system’s gotten firmer to deal with its shortcomings, so the feeling is not as magical. As the steering and brakes are more traditional now, one could argue there’s more to offer sporting drivers, too, and the current C5 is actually quite attractive. But, it’s simply not a big seller.

Ive got the previous model with the last version of hydra-active, its a MK2 built after MK3 production began, they run standard brakes big discs all round be cause making the other system work with EBS was too challenging, ride and handling are excellent and this is my second C5, I mean why would you buy anything else

The hydraulic do go wrong but its a very simple car to repair once you get your head around it a suspension leg failed on my car I fixed it now predictably the other side failed parts are on the way but this time I’ll teach a garage a friend runs how to change them.

If the suspension fails completely you can still drive it with no damage at speeds up to 55 mph.

Great article. I know absolutely nothing about the CX but have always liked the styling. It’s a shame though that the instrument panel changed so much versus the one in the DS. Sure the DS looks cool and is technically interesting but for me a big part of the charm was the low-plastic, durable looking interior.

The CX and Peugeot 405 started the plasticky trend in French interiors which remains, at least in my mind, to this day.

A recent Citroën interior.

And their latest in the new Cactus model.

Those interiors look fantastic. I don’t know why I said French interiors still look plasticky, that is wrong. I guess as an American I am left with what French cars looked like when they left the US market. Come to think of it I saw an ’05ish Renault Megane once and thought the interior was even nicer than the Golf’s.

“The CX and Peugeot 405 started the plasticky trend in French interiors which remains, at least in my mind, to this day.”

I’ll agree with that. Citroen dabbled in losing me with the CX (tho a moot point in the USA!) as Peugeot dabbled in losing me with the 505. Interesting that both vehicles went through a dizzying array of some really nice variants with a lot of improved engines. And it kinda went down hill from there.

Mines all leather previous C5 was cloth not much wrong with Citroen interiors.

Excellent article !

The Comotor engine project ended in tears, yet 39 new Comotor blocks became the heart of the ultra-rare

Van Veen OCR 1000 bike. Kreidler-importer Henk van Veen wanted to build the “ultimate bike” in the early seventies. His first Van Veen bike was presented in 1976, 100 hp at 6,500 rpm and a top speed of 200 km/h. Only 38 of them were officially built, and many years later an enthusiast built number 39 from the factory’s stock.

The last photograph looks like what a new Pirus will look like in 2047. It looked like a spaceship in the 70’s, now it looks like any late model hybrid. Nice article on these cars. Too bad the quality could not keep up with the engineering, and the Wankel did not prove to be the engine of the future. Even the dash looks current to what you see today. The interior quality and materials are far superior to what you see today, however. Really were cars that were ahead of their time. If they still rolled off the assembly line today, these cars would look up to date. Right car, wrong time.

My CX had the most conversation generating ashtray:

That looks just like the interior on mine. The ashtray was awesome.

And the radio at the right place, very convenient.

I submit that the spiritual cousin of this car in a number of respects is the Mazda HB Cosmo RE. The Cosmo didn’t have Citroën’s hydraulic system, but it was about as eccentric in other respects, had a similarly self-conscious futuristic vibe (particularly the early HBs with pop-up headlights), and had the rotary engine the CX never got — including a turbocharged version (with four-speed automatic, if you please).

Mazdas dont ride and handle very well either and the rotaries were only marginal in reliability improvements compared to NSU Citroen made the right move abandoning rotaries and even into the late 90 Citroens and Peugeots could not be had with turbo diesel automatics and having owned a couple only a fool would want an auto they detract from the driving experience too much.

The last time one of these appeared on the cohort it was ignored well done Perry I see Citroens of all models in my travels one of the hazards of driving one I guess, I’ll start shooting them again since there seems to be some interest in the brand Certainly very advanced other than the engine for their time never mind other makers were building fairly comfortable good roadholding cars by the 90 none have ever got close to the French.

I know this comment will illicit some chuckles and head shaking, but I’m going to say it anyway…those last “big” Citroens had much in common with the Chrysler LH’s, at least when they were equipped with the sport suspension and speed sensitive power steering, like ours is (’96 New Yorker). My car is probably more of a cousin to the SM-same longitudnal engine layout with a 24 valve V6 driving the front wheels, and fully independent suspension as well. How many of you have actually driven one of these that has been properly sorted ? They are unusually nimble and have nicely weighted steering. They aren’t sports cars, but they are great road cars.

‘Last Big Citroens’? Youve not seen a C6 then I posted one on the cohort last year in black very nice car in the large variety.

Ahh – the old “is the C6 REALLY a Citroen?” debate, episode MLMCXVIII…….

yeah its real a LWB version of my current car

Those ugly black moldings on the feature car do a really good job ruining the otherwise attractive lines of it. I’d much rather have door dings than those.

I’m normally not a huge fan of Citroens of the modernist design but I would say the CX would be the one I’d pick out of all them, and the original interior is very cool.

What doomed the car from a practical point of view was that it was very very cramped. That interior shot is from the Prestige model, which had an additional 25 cm in the back seat. The standard model had an abysmally small back seat. It was (for European standards) a full size car with a full size price, but with compact car interior dimensions. Seen in the flesh, it is very very low to the ground, even while “standing up” from the parked position. It was expensive as a Mercedes W123 but without the prestige. It was a car for those in the know, but for everybody else it was simply an inferior product.

With all these new four door coupes nowadays, I think it’s fun viewing the CX but also the DS as a sort of ancient four door coupe. It’s a closed coupled sedan, as the Americans would say. Or a sports sedan as the English would say. It’s a very impractical four doored car seating four people for sustained travel, and not much else. But doing it in style. And style it had in loads…

Ah ha I wondered if they came in two sizes the one I shot years ago for the cohort seemed smaller, but sports sedan they are I chased one through Bells line of road between Richmond and Lithgow in NSW with tuned Holden Commodore and had trouble staying with it I was using opposite lock on turns the Citroen was just gliding around, wet road not helping me but seemingly not bothering the French car, impressed me quite a lot coz that VH Dore was fast.

Ingvar, you bring up a point that I was ruminating on while painting this afternoon: when the CX came out, it was rather confusing, to me a swell as probably lots of other folks. It was clearly pegged in below the DS, in terms of size, engine capacity, and other amenities. It was almost as if Citroen had in mind a larger replacement for the DS, yet to come.

The first versions of the CX, the 2000 and 2200, were rather modestly powered. The reception, as I remember, was not all that positive. They came across almost as “strippers”. Sales started out weak, unlike the DS which got a huge number of orders from the Paris Auto Show.

The CX only seemed to really hit its stride some years later; it took quite a while. In retrospect, it seems Citroen may have rather blown the intro. Perhaps they should have started with the Prestige, and bring out lesser models later. It was a decidedly weak introduction.

As others have said: the CX was never on the same plane as the DS, in terms of being inspired, its overall impact, seen as a successful competitor to the other cars in its class, being years ahead of everyone else, and being almost timeless. I know which one I’d rather have.

I don’t see it as being “pegged in” lower than the DS. For the Europeans, I think it was a direct replacement, or as exact as could be after almost 25 years with the DS. Remember, most sold in Europe where the stripper ID models, the top of the line fuel injected DS23 was in another league, and not that common. Production numbers were very flat, from 1960 and onwards, they made about 80-100 000 cars a year. But they sold in those numbers all up until the end, with 1970 being an all time high. So, it sold quite well quite late as well.

Also, the company had always been cash-strapped, and with compromises there’s always something that has to go. They invested quite heavily in an industrial infrastructure in hydropneumatics. They invented sliding valves for the plumbing that had an unprecedented low tolerance. And they became unique in that area. For a very long time, there was no one else to deliver that stuff but them. The r&d for of all that cost a lot of money, also the entire production lines and productional facilities.

But engines has never been their forté. Even the DS had to do with an evolution of the Traction Avant-engine, with a cross flow top but retaining only three main bearings. Five main bearings came in ’65, and then the fuel injection. I don’t really know what engines the CX started out with, but it seems it was the old 2.0 and 2.2 litre-engines from the DS20/DS21. The 2.4 from the DS23 came in later, while the smaller engines was replaced with the Renault-sourced Douvrin-engines in the early 80’s. It seems that the 2.5-engine is a development of the old DS23-block, but I could be wrong. And I don’t know if the diesel-version were converted from that, or if they were Peugeot-units. The diesel could be the so called Indenor-engine from Peugeot. In any case, they were spreading the butter extremely thin, and all the development in the world couldn’t help the Turbo 2 from being a very thirsty car for being only four cylinder.

Another thing I’ve read somewhere was that the Prestige was supposed to be the normal car, and that the shorter car came in later in development as an afterthought. Supposedly, it was the ’73 fuel crisis that put an end to those plans of giving all the people that executive lounge feel. It makes sense, in only having one length in wheelbase, and that being the same for the sedan and the station wagon. And as said, the shorter car is really really cramped. But I think it’s an apocryphal story, considering how good looking the shorter car is compared to the more hunchbacked Prestige. It wouldn’t make sense if they didn’t design that first.

Overall length CX is 9.5 inches shorter than the DS; however

Interior CX is 2 inches wider across front seat and 3.5 inches across rear. But less rear headroom in CX.

I’d say from the crossover in dimensions (few though I’ve given), it was to be a replacement for the DS. That’s how Citroenet describes it.

Citroenet also features early sketches and prototypes, all of which look closer to the sedan than the Prestige in wheelbase.

Maybe Citroen figured the smaller dimensional aspects would be overlooked when it was planned to be released with the wow factor of either the rotary or the SM engine.

Well, the CX was designed with the longer, lower, wider aspect still intact. When I see one nowadays I can’t fathom how low it is. But also, the CX had more effecient packaging, with the front obviously being shorter than the DS. With it’s front/mid-engine placement, the DS isn’t really revolutionary in packaging efficiency. So, the difference in length should be in the front, courtesy of the transverse engine-placement of the CX.

I’m actually quite surprised to learn how long, or rather short, the standard-wheelbase car is. At 183″ it’s only 6″ longer than a current Honda Civic, for example. And 7″ shorter than a Volvo 240, for a somewhat-competitor that would have been on the market at the same time. They look bigger than they are–perhaps it’s that proportion of height to length that gives an illusion of a bigger car. Even the Prestige, which looks almost limousine-like from some angles with those long rear doors, is about the same length as a current Honda Accord.

Guess that lack of rear overhang makes a big difference…

I know the story, as per the other CC entries on these Citroens, but its too bad these didn’t get some real power under the hood. A turbo’d Mazda rotary would make one of these a lot of fun, assuming the chassis could handle it….

Thanks Perry for the great article. These cars have been overlooked for too long – the only CX specific book I’ve found is a recent Brooklands compilation of road tests and magazine articles.

I sometimes see really well kept examples go through the classic auctions and achieve virtually nothing. Must be heartbreaking for the consigning owners, not so much about the money, but the realisation no one really cares about them.

An (architect, hah!) I worked with years ago had a CX 2200 and loved it. It was always the car I’d borrow (and he’d say “You bend it, you buy it” each time when handing over the key). I loved it. Yes, it was slow off the line, I think too much is being made of the pushrod motor harshness and vibration in these parts.

An issue not addressed so far, and the one which consigned Australian market cars to a premature end, is the self destructing interiors. The vinyl covered foam moulded door cards, the upholstery fabric – a nylon herringbone weave – and the seat bases themselves did not like summers beneath the vast glass areas. I’ve ridden in a few Ds (never driven one, however) and the CX experience is actually better. This car deserved better. I dislike the gradual erosion of the design over time, yep the sperical ashtray of the 2400 is cool but every other aesthetic change they can keep.

I will concede that a vertically mounted radio/cassette between the front seats was not a practical installation. that needed an overhead console a la TBird.

As in most countries a weak dealer network did them no favours here.

Perry, please find a Safari wagon next. Fingers crossed that the CC effect kicks in soon…

Edit: To reiterate Bryce’s comment above, interested parties should seek out a Citroen C6. Built to order only avant garde goodness, the view when one approaches is unique. The interior design is a revelation. Sadly all of this is overwhelmed by the depreciation they suffer. Not an investment by any measure.

I love that ad-a play on the old German phrase for living the good life, “Live like God in France!”

Great post Perry. I saw the pics on the Cohort but, as often happens with me, it went on the back burner. I did do a mini CC on the Citroen CX, however: https://www.curbsideclassic.com/blog/miniature-curbside-classic-citroen-cx-by-playart-and-nissan-juke-by-tomica-an-eccentric-pair/

I like the Juke, too! I would prefer it weren’t conceived as a mini SUV, and rather, as a less-cheap car in the Fiesta/Focus mold, but one with a six-speed and front-wheel drive is probably the most fun you’ll have in a Japanese small car these days (the Civic Si is NOT small!).

I, too, like the earlier Citroen CXs; maybe a turbo or turbodiesel from a later model in an earlier version would make the ultimate combo.

I have the Haynes Classic book on Citroen and in it there is a photo of a first-year CX in orange with orange interior. That’s the one I’d want!

BTW the Haynes Classic Marques books are a very good resource for anyone interested in European car history. I have the ones for Citroen, Volvo, Lotus, MG, Aston Martin and Jaguar. Not super in-depth but very good general history and lots of nice pics. It was a big help in my Jag XJ12 L post!

Another awesome story. Although I’ve never seen a Citroen CX in person, no thanks to the lack of any dealer/service network, which is unforgivable, I’ve seen pictures of the car, and IMHO, it’s the best looking Citroen since the DS and SM.

This car still parks in Manhattan, seen between 8th and 9th Avenues, 26th and 29th Streets, and looking somewhat worse for wear. The owner uses wooden stands to preserve bumper height after the suspension depressurizes. It’s a calming presence for those who remember.

CC Effect, of sorts: I saw a blue CX just like the curbside New York car featured here, last night. On TV … it plays a role in a series called The Land of Women, set in Spain, and starring Eva Longoria.

Weird, but very futuristic for its time.

Citroen was at the forefront of design and innovation.

“Citroen was at the forefront of design and innovation.”

It didn’t do them any good. PSA could cancel it at any time – and hardly anyone would notice.

Glaring shortcomings? This is an over-statement. I have been lucky enough to drive one of these. It is also an overstatement to describe the difference in driving style as being such that you are required to re-learn how to drive. It takes a only few moments to adjust, little to challenge any but most mince-thick motorist. The steering is sublime – nothing I’ve driven is as pleasing.