After the lively discussion here about the first mass-produced front wheel drive cars the other day, I felt a powerful urge to write about J.W. Christie’s highly-innovative but ultimately ill-fated racing cars, which are the undisputed true pioneers of front wheel drive. Regretfully I don’t have the time for that right now, and I did just come across this excellent article on the subject by Paul C. Wilson in the June 1976 Road and Track, so I’ll leave it to him.

There were a few crude little buggies with powered front wheels built in France before Christie’s FWD cars, but they had very substantial limitations, and not generally considered significant in the history of FWD. Christie’s carefully-considered concept, to eliminate the large, heavy and complex drive trains of the time with a very direct and integrated FWD system with independent front suspension (via sliding pillars) was truly one of the genius developments of the early evolution of the car. It was very functional, and was specifically designed to provide a number of key benefits, including improved traction, low drive-line losses, and to place the chassis (and driver) mich closer to the ground for improved center of gravity, reduced aero drag, and lightness. It did only have two forward gears, but with the very large and slow-turning (up to 20 liter) engines, that was not a handicap at all, and not atypical for the times.

But unfortunately, like so many other geniuses, while his overall conception was brilliant, it was severely hampered by his stubborn adherence to certain limiting factors, like the “atmospheric” intake valves, which relied on a delicate calibration to work. Ironically, that was already archaic, and everyone else had moved to positive intake valve actuation, especially in racing car engines. His surface radiators were another shortcoming, as they rarely stayed together long enough to survive the grueling long-distance races. His cars ended up being mostly successful in sprints for that reason.

His cars were derided as “freaks”, and “monstrosities” because of their innovative design. Americans were just not ready to embrace FWD.

Ironically, it would be another American racing car, Harry Miler’s brilliant 1924 FWD 122 Indy racer, that would really put front wheel drive on the map, and was the true inspiration for the Cord L29 and pretty much every other production FWD car to come. This is a 1928 Miller 91, and I consider these cars to be among the most exquisitely beautiful and brilliant cars ever. I fell in love with these when I saw pictures of it as a kid, and it’s deeply imprinted on me as the very ideal of the essence of an automobile. Sheer perfection.

Back to poor Christie, who was just ahead of his time, and perhaps lacked the more balanced genius of Harry Miller.

Here’s a shot from the web of Christie’s giant 20 liter(!) V4 racer, with dual front wheels to improve traction.

Christie even built a dual-engine racer for all-wheel drive. How’s that for pioneering? FWD as well as AWD! The rear engine crapped out in its first outing, reducing it back to FWD and a lot of dead weight in the rear.

One of the things the fans didn’t like about the Christie cars was that they didn’t have the tail-out attitude of the RWD cars on the loos gravel and dirt roads and tracks. Understeer was invented here. As well as torque steer. Actually, worse than that: in power on curves, there were some nasty whip and jolting from the front wheels, as conventional (not constant velocity) universal joints were used on the front axle.

Here’s a great shot from a grudge race in 1908, with three of the hottest racing cars and drivers that year. It’s not hard to see why folks thought the Christie was a “monster”; the race cars of the time had already begun to develop a distinctive style, and the Christie defied that utterly.

His later racers, with its engine slanted back under a hood, were much more graceful. The general configuration of his cars was radically ahead of the times, as they were the very first racing cars to be truly low to the ground. And the traction from the front engine over the wheels gave a big improvement to traction on the dirt roads that were used for racing at the time.

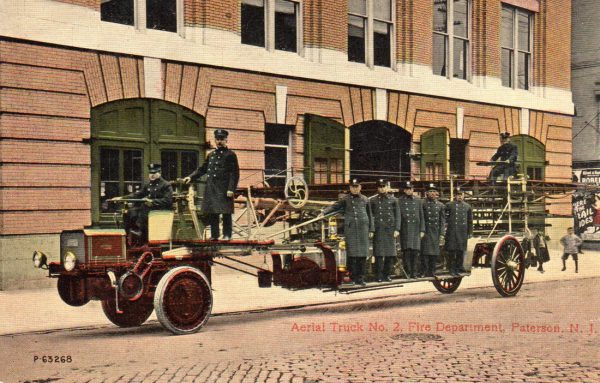

After Christie retired from racing and sold his last car in 1909, hetried to develop his Direct Action Drive for other applications, like fire engines. But it all went nowhere; as is commonly the case when someone is simultaneously way ahead of the times as well as being behind them, in certain regards.

Ah, the curse of genius combined with too much money. A poorer man might have been forced to listen to reason by his backers, or might have had to use ‘off-the-shelf’ technology to cut costs. Unfettered imagination is a a beautiful but dangerous thing.

Wonder if Christie paid royalties to Selden? While Selden was demanding royalties from anyone who put the engine in the front of a car, his design was front wheel drive, so Christie’s design would infringe the most.

_That_ Walter Christie ?.. I’ve heard that he designed FWD race cars in the beginning of the century, even found the patent drawing of his FWD transmission, but never saw the photos, thanks for this article !

Christie’s patent drawing, as published in AutoReview magazine in 2002; it’s curious that he used single Cardan joints to drive the front wheels – not CV joints usually employed in FWD systems. Perhaps Christie even didn’t understand the need for CV joints in such application, or just didn’t care much for durability which was not a priority for a race car.

Christie’s M1928 tank was rejected by the US Army for various reasons (armor thickness, suitability for combat doctrine, etc.), so it was exported illegally to the Soviets, who improved it into the BT series, which were the perhaps the best tanks of the ’30s. The T-34 was a derivative, though without Christie’s removable tracks.

What would the Soviets have done without aid from American capitalists?

The British also use Christie’s suspension in some of their Cruiser tanks. This was eventually replaced by the less space-hogging Horstmann layout in the excellent Centurion.

The British also use Christie’s suspension in some of their Cruiser tanks.

The Cruiser Mk III was superseded by the Crusader, also with Christie suspension. The Crusader saw a lot of action in North Africa.

Biggest problem the Brits had was designing tanks able to mount their larger high-velocity guns, because of small turret-rings. Not until the late-war Comet did they finally have a domestic medium (UK: heavy cruiser) tank with firepower comparable to the much more numerous Mk IV Special, T-34/85, & 76mm Sherman.

In kinetic energy terms, all British AT guns were competitive with German guns of comparable caliber. This remained true several decades later.

Fascinating stuff. But front wheel drive was “invented” even earlier – the Cugnot steam wagon of 1770 was FWD 🙂

Always enjoy reading about inventors/fabricators in the earlier parts of the 20th Century. Especially the more non conventional forward thinking types such as Walter Christie.

Fascinating story.

Walter Christie has always been a fascination of mine. While his cars were incredibly stupid-crazy for their day, his tank designs were incredibly advanced and realistic in a technological sense. The Army’s objections to his tanks for not fitting in to combat doctrine was due to the Army’s expectations of a tank going cross-country at 20-25mph while supporting advancing infantry (think Battle of the Somme with tanks), while his designs were doing 50mph flat out (think Blitzkreig).

The Soviets fell all over themselves to adopt his designs, and as Neil has mentioned, they were the best tanks available in the pre-WWII era. The realization that the Soviets were still using a lot of his design parameters for the T-35, fifteen years after he originally presented his ideas to the US Army, says a lot in itself.

Very informative , as always.